(Press-News.org) DURHAM, N.H. – Climate modelers from the University of New Hampshire have shown that the most likely explanation for the initiation of Antarctic glaciation during a major climate shift 34 million years ago was decreased carbon dioxide (CO2) levels. The finding counters a 40-year-old theory suggesting massive rearrangements of Earth's continents caused global cooling and the abrupt formation of the Antarctic ice sheet. It will provide scientists insight into the climate change implications of current rising global CO2 levels.

In a paper published today in Nature, Matthew Huber of the UNH Institute for the Study of Earth, Oceans, and Space and department of Earth sciences provides evidence that the long-held, prevailing theory known as "Southern Ocean gateway opening" is not the best explanation for the climate shift that occurred during the Eocene-Oligocene transition when Earth's polar regions were ice-free.

"The Eocene-Oligocene transition was a major event in the history of the planet and our results really flip the whole story on its head," says Huber. "The textbook version has been that gateway opening, in which Australia pulled away from Antarctica, isolated the polar continent from warm tropical currents, and changed temperature gradients and circulation patterns in the ocean around Antarctica, which in turn began to generate the ice sheet. We've shown that, instead, CO2-driven cooling initiated the ice sheet and that this altered ocean circulation."

Huber adds that the gateway theory has been supported by a specific, unique piece of evidence—a "fingerprint" gleaned from oxygen isotope records derived from deep-sea sediments. These sedimentary records have been used to map out gradient changes associated with ocean circulation shifts that were thought to bear the imprint of changes in ocean gateways.

Although declining atmospheric levels of CO2 has been the other main hypothesis used to explain the Eocene-Oligocene transition, previous modeling efforts were unsuccessful at bearing this out because the CO2 drawdown does not by itself match the isotopic fingerprint. It occurred to Huber's team that the fingerprint might not be so unique and that it might also have been caused indirectly from CO2 drawdown through feedbacks between the growing Antarctic ice sheet and the ocean.

Says Huber, "One of the things we were always missing with our CO2 studies, and it had been missing in everybody's work, is if conditions are such to make an ice sheet form, perhaps the ice sheet itself is affecting ocean currents and the climate system—that once you start getting an ice sheet to form, maybe it becomes a really active part of the climate system and not just a passive player."

For their study, Huber and colleagues used brute force to generate results: they simply modeled the Eocene-Oligocene world as if it contained an Antarctic ice sheet of near-modern size and shape and explored the results within the same kind of coupled ocean-atmosphere model used to project future climate change and across a range of CO2 values that are likely to occur in the next 100 years (560 to 1200 parts per million).

"It should be clear that resolving these two very different conceptual models for what caused this huge transformation of the Earth's surface is really important because today as a global society we are, as I refer to it, dialing up the big red knob of carbon dioxide but we're not moving continents around."

Just what caused the sharp drawdown of CO2 is unknown, but Huber points out that having now resolved whether gateway opening or CO2 decline initiated glaciation, more pointed scientific inquiry can be focused on answering that question.

Huber notes that despite his team's finding, the gateway opening theory won't now be shelved, for that massive continental reorganization may have contributed to the CO2 drawdown by changing ocean circulation patterns that created huge upwellings of nutrient-rich waters containing plankton that, upon dying and sinking, took vast loads of carbon with them to the bottom of the sea.

INFORMATION:

The article is available to download here: http://www.nature.com/nature/journal/v511/n7511/full/nature13597.html.

The National Science Foundation provided funding for the project and the computing was carried out using clusters at Purdue University's Rosen Center for Advanced Computing.

The University of New Hampshire, founded in 1866, is a world-class public research university with the feel of a New England liberal arts college. A land, sea, and space-grant university, UNH is the state's flagship public institution, enrolling 12,300 undergraduate and 2,200 graduate students.

Antarctic ice sheet is result of CO2 decrease, not continental breakup

2014-07-30

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

NASA catches two tropical troublemakers in Northwestern Pacific: Halong and 96W

2014-07-30

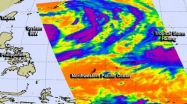

There are two tropical low pressure areas in the Northwestern Pacific Ocean today and they're close enough to each other to be captured in one image generated from data gathered by NASA's Aqua satellite.

NASA's Aqua satellite flew over both Tropical Storm Halong and developing System 96W early on July 30 and the Atmospheric Infrared Sounder (AIRS) instrument captured infrared data on them in one image. Both systems show powerful thunderstorms stretching high into the troposphere with cloud top temperatures as cold as -63F/-52C. Those thunderstorms have the potential for ...

Watching Schrödinger's cat die (or come to life)

2014-07-30

One of the famous examples of the weirdness of quantum mechanics is the paradox of Schrödinger's cat.

If you put a cat inside an opaque box and make his life dependent on a random event, when does the cat die? When the random event occurs, or when you open the box?

Though common sense suggests the former, quantum mechanics – or at least the most common "Copenhagen" interpretation enunciated by Danish physicist Neils Bohr in the 1920s – says it's the latter. Someone has to observe the result before it becomes final. Until then, paradoxically, the cat is both dead and ...

Fear of losing money, not spending habits, affects investor risk tolerance, MU study finds

2014-07-30

As the U.S. economy slowly recovers, many investors remain wary about investing in the stock market. Investors' "risk tolerance," or their willingness to take risks, is an important factor for investors deciding whether, and how much, to invest in the stock market. Now, Michael Guillemette, an assistant professor of personal financial planning in the University of Missouri College of Human Environmental Sciences, along with David Nanigian, an associate professor at the American College, analyzed the causes of risk tolerance and found that loss aversion, or the fear of losing ...

When cooperation counts

2014-07-30

Everybody knows the shortest distance between two points is a straight line, and now Harvard researchers have evidence that sperm have been taking the familiar axiom to heart.

Though competition among individual sperm is usually thought to be intense, with each racing for the chance to fertilize the egg, Harvard scientists say in some species, sperm form cooperative groups that allow them to take a straighter path to potential fertilization.

A new study, conducted by Heidi Fisher, a post-doctoral student working in the lab of Hopi Hoekstra, Howard Hughes Investigator ...

Scientists call for new strategy in pursuit of HIV-free generation

2014-07-30

In light of the recent news that HIV has been detected in the Mississippi baby previously thought to have been cured of the disease, researchers are assessing how to help those born to HIV-infected mothers. These infants around the world are in need of new immune-based protective strategies, including vaccines delivered to mothers and babies and the means to boost potentially protective maternal antibodies, say researchers who write in the Cell Press journal Trends in Microbiology on July 30th.

"There is a real need for additional HIV-1 prevention methods for infants," ...

Study: Marine pest provides advances in maritime anti-fouling and biomedicine

2014-07-30

A team of biologists, led by Clemson University associate professor Andrew S. Mount, performed cutting-edge research on a marine pest that will pave the way for novel anti-fouling paint for ships and boats and also improve bio-adhesives for medical and industrial applications.

The team's findings, published in Nature Communications, examined the last larval stage of barnacles that attaches to a wide variety of surfaces using highly versatile, natural, possibly polymeric material that acts as an underwater heavy-duty adhesive.

"In previous research, we were trying to ...

Dissolvable fabric loaded with medicine might offer faster protection against HIV

2014-07-30

Soon, protection from HIV infection could be as simple as inserting a medicated, disappearing fabric minutes before having sex.

University of Washington bioengineers have discovered a potentially faster way to deliver a topical drug that protects women from contracting HIV. Their method spins the drug into silk-like fibers that quickly dissolve when in contact with moisture, releasing higher doses of the drug than possible with other topical materials such as gels or creams.

"This could offer women a potentially more effective, discreet way to protect themselves from ...

NASA sees zombie Tropical Depression Genevieve reborn

2014-07-30

Infrared imagery from NASA's Aqua satellite helped confirm that the remnant low pressure area of former Tropical Storm Genevieve has become a Zombie storm, and has been reborn as a tropical depression on July 30.

Tropical Storm Genevieve weakened to a tropical depression on Sunday, July 27 and the National Hurricane Center issued their final advisory on the system as it was entering the Central Pacific. Now, after three days of living as a remnant low pressure area, Genevieve reorganized and was classified as a tropical depression again.

The Tropical Rainfall Measuring ...

Birthweight and breastfeeding have implications for children's health decades later

2014-07-30

Young adults who were breastfed for three months or more as babies have a significantly lower risk of chronic inflammation associated with cardiovascular and metabolic diseases, according to research from the Brown School at Washington University in St. Louis.

"This study shows that birthweight and breastfeeding both have implications for children's health decades later," said Molly W. Metzger, PhD, assistant professor at the Brown School and a co-author of the study with Thomas W. McDade, PhD, of Northwestern University.

"Specifically, we are looking at the effects ...

Appreciation for fat jokes, belief in obese stereotypes linked

2014-07-30

BOWLING GREEN, O.—From movies to television, obesity is still considered "fair game" for jokes and ridicule. A new study from researchers at Bowling Green State University took a closer look at weight-related humor to see if anti-fat attitudes played into a person's appreciation or distaste for fat humor in the media.

"Weight-Related Humor in the Media: Appreciation, Distaste and Anti-Fat Attitudes," by psychology Ph.D. candidate Jacob Burmeister and Dr. Robert Carels, professor of psychology, is featured in the June issue of Psychology of Popular Media Culture.

Carels ...