(Press-News.org) Inspired by the Red Queen in Lewis Carroll's Through the Looking Glass, collaborators from the University of Illinois and National University of Singapore improved a 35-year-old ecology model to better understand how species evolve over decades to millions of years.

The new model, called a mean field model for competition, incorporates the "Red Queen Effect," an evolutionary hypothesis introduced by Lee Van Valen in the 1970s, which suggests that organisms must constantly increase their fitness (or ability to survive and reproduce) in order to compete with other ever-evolving organisms in an ever-changing environment.

"Well, in our country," said Alice, still panting a little, "you'd generally get to somewhere else — if you run very fast for a long time, as we've been doing."

"A slow sort of country!" said the Queen. "Now, here, you see, it takes all the running you can do, to keep in the same place. If you want to get somewhere else, you must run at least twice as fast as that!"

The mean field model assumes that new species have competitive advantages that allow them to multiply, but over time new species with even better competitive advantages will evolve and outcompete current species, like a conveyor belt constantly moving backwards.

The model gets its name from field theory, which describes how fields, or a value in space and time, interact with matter. A field is like a mark on a map indicating wind speeds at various locations to measure the wind's velocity. In this ecological context, the "fields" approximate distributions of species abundances.

Ecologists can use models to predict what happens next and diagnose sick ecosystems, said first author James O'Dwyer, an assistant professor of plant biology at Illinois and member of the Institute for Genomic Biology.

The mean field model has improved a fundamental ecology model, called neutral biodiversity theory, which was introduced by Stephen Hubbell in the 1970s. Neutral theory does not account for competition between different species, thus considering all species to be selectively equal.

Neutral theory can predict static distributions and abundances of species reasonably well, but it breaks down when applied to changes in communities and species over time. For instance, the neutral model estimates that certain species of rain forest trees are older than Earth.

"The neutral model relies on random chance," O'Dwyer said. "It's like a series of coin flips and a species has to hit heads every time to become very abundant. That doesn't happen very often."

Imagine these ecological models on a spectrum, O'Dwyer says.

"At one end, we have this neutral model with very few parameters and very simple mechanisms and dynamics, but at the other end, we have models where we try to parameterize every detail," O'Dwyer said. "What's been hardest is to take one or two steps down this spectrum from the neutral model without being sucked down to this very complicated end of the spectrum."

By creating a more realistic model that incorporates species differences, O'Dwyer and co-author Ryan Chisholm, an assistant professor at National University of Singapore, have taken an important step down that spectrum.

"Our model is not the ecological equivalent of Einstein's General Theory of Relativity, which was a conceptual leap for physics," O'Dwyer said. "It is an incremental step at this point. But we will need those conceptual leaps that incorporate the best parts of different models to really understand complex ecological systems better."

O'Dwyer and Chisholm recently reported this work in Ecology Letters. The Templeton World Charity Foundation (grant # TWCF0079/AB47) supported O'Dwyer's work.

The Institute for Genomic Biology (IGB) is dedicated to interdisciplinary genomic research related to health, energy, agriculture and the environment. The Institute's cadre of world-class scientists, collaborative laboratories, and state-of-the-art equipment create an environment that inspires discovery and stimulates bioeconomic development at the University of Illinois. Learn more at http://www.igb.illinois.edu.

INFORMATION: END

Classic Lewis Carroll character inspires new ecological model

2014-07-30

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

Diverticulitis patients reveal psychological, physical symptoms long after acute attacks

2014-07-30

UCLA researchers interviewed people with diverticulitis and confirmed that many suffer psychological and physical symptoms long after their acute illness has passed.

For the study, published this week in the peer-reviewed journal Quality of Life Research, a UCLA team led by Dr. Brennan Spiegel interviewed patients in great detail about the symptoms they experience weeks, months or even years after an acute diverticulitis attack. Their striking findings add to growing evidence that, for some patients, diverticulitis goes beyond isolated attacks and can lead to a chronic ...

Finding quantum lines of desire

2014-07-30

Groundskeepers and landscapers hate them, but there is no fighting them. Called desire paths, social trails or goat tracks, they are the unofficial shortcuts people create between two locations when the purpose-built path doesn't take them where they want to go.

There's a similar concept in classical physics called the "path of least action." If you throw a softball to a friend, the ball traces a parabola through space. It doesn't follow a serpentine path or loop the loop because those paths have higher "actions" than the true path.

But what paths do quantum particles, ...

Tidal forces gave moon its shape, according to new analysis

2014-07-30

The shape of the moon deviates from a simple sphere in ways that scientists have struggled to explain. A new study by researchers at UC Santa Cruz shows that most of the moon's overall shape can be explained by taking into account tidal effects acting early in the moon's history.

The results, published July 30 in Nature, provide insights into the moon's early history, its orbital evolution, and its current orientation in the sky, according to lead author Ian Garrick-Bethell, assistant professor of Earth and planetary sciences at UC Santa Cruz.

As the moon cooled and ...

Target growth-driving cells within tumors, not fastest-proliferating cells

2014-07-30

BOSTON –– Of the many sub-groups of cells jockeying for supremacy within a cancerous tumor, the most dangerous may not be those that can proliferate the fastest, researchers at Dana-Farber Cancer Institute report in a paper appearing in an advance online publication of the journal Nature. The findings have important implications for the treatment of cancer with precision medicines, the study authors explained: Doctors need to ascertain which cell subgroups are truly driving the tumor's growth and metastasis and select drugs that target the critical genes within those cells. ...

ALMA finds double star with weird and wild planet-forming discs

2014-07-30

BOWLING GREEN, O.—From movies to television, obesity is still considered "fair game" for jokes and ridicule. A new study from researchers at Bowling Green State University took a closer look at weight-related humor to see if anti-fat attitudes played into a person's appreciation or distaste for fat humor in the media.

"Weight-Related Humor in the Media: Appreciation, Distaste and Anti-Fat Attitudes," by psychology Ph.D. candidate Jacob Burmeister and Dr. Robert Carels, professor of psychology, is featured in the June issue of Psychology of Popular Media Culture.

Carels ...

Innovative scientists update old-school pipetting with new-age technology

2014-07-30

CAMBRIDGE, Mass. (July 30, 2014) A team of Whitehead Institute researchers is bringing new levels of efficiency and accuracy to one of the most essential albeit tedious tasks of bench science: pipetting. And, in an effort to aid the scientific community at large, the group has established an open source system that enables anyone to benefit from this development free of charge.

Dubbed "iPipet," the system converts an iPad or any tablet computer into a "smart bench" that guides the execution of complex pipetting protocols. iPipet users can also share their pipetting designs ...

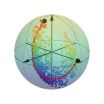

Mapping the optimal route between 2 quantum states

2014-07-30

As a quantum state collapses from a quantum superposition to a classical state or a different superposition, it will follow a path known as a quantum trajectory. For each start and end state there is an optimal or "most likely" path, but it is not as easy to predict the path or track it experimentally as a straight-line between two points would be in our everyday, classical world.

In a new paper featured this week on the cover of Nature, scientists from the University of Rochester, University of California at Berkeley and Washington University in St. Louis have shown ...

Young binary star system may form planets with weird and wild orbits

2014-07-30

Unlike our solitary Sun, most stars form in binary pairs -- two stars that orbit a common center of mass. Though remarkably plentiful, binaries pose a number of questions, including how and where planets form in such complex environments.

While surveying a series of binary stars with the Atacama Large Millimeter/submillimeter Array (ALMA), astronomers uncovered a striking pair of wildly misaligned planet-forming disks in the young binary star system HK Tau. These results provide the clearest picture ever of protoplanetary disks around a double star and could reveal important ...

Scientists reproduce evolutionary changes by manipulating embryonic development of mice

2014-07-30

A group of researchers from the University of Helsinki and the Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona have been able experimentally to reproduce in mice morphological changes which have taken millions of years to occur. Through small and gradual modifications in the embryonic development of mice teeth, induced in the laboratory, scientists have obtained teeth which morphologically are very similar to those observed in the fossil registry of rodent species which separated from mice millions of years ago.

To modify the development of their teeth, the team from the Institute ...

Conservation scientists asking wrong questions on climate change impacts on wildlife

2014-07-30

Scientists studying the potential effects of climate change on the world's animal and plant species are focusing on the wrong factors, according to a new paper by a research team from the Wildlife Conservation Society, University of Queensland, and other organizations. The authors claim that most of the conservation science is missing the point when it comes to climate change.

While the majority of climate change scientists focus on the "direct" threats of changing temperatures and precipitation after 2031, far fewer researchers are studying how short-term human adaptation ...