Diverticulitis patients reveal psychological, physical symptoms long after acute attacks

Findings of UCLA study could lead to better disease management

2014-07-30

(Press-News.org) UCLA researchers interviewed people with diverticulitis and confirmed that many suffer psychological and physical symptoms long after their acute illness has passed.

For the study, published this week in the peer-reviewed journal Quality of Life Research, a UCLA team led by Dr. Brennan Spiegel interviewed patients in great detail about the symptoms they experience weeks, months or even years after an acute diverticulitis attack. Their striking findings add to growing evidence that, for some patients, diverticulitis goes beyond isolated attacks and can lead to a chronic condition that mimics irritable bowel syndrome.

As they age, most people develop diverticulosis, a disorder characterized by the formation of pouches in the lining of the colon. More than 50 percent of people over 60 have the condition, but the pouches usually don't cause any problems. Occasionally, however, the pouches become inflamed, leading to a related disorder called diverticulitis, which causes pain and infection in the abdomen. Doctors usually treat diverticulitis with antibiotics, or in more severe cases, surgery.

The condition has long been thought to be acute with periods of relative silence in between attacks, but according to researchers, that's not true for everyone. Some patients experience ongoing symptoms.

In an earlier study, Spiegel and colleagues found that people suffering from diverticulitis have a four-fold higher risk of developing IBS after their illness, a condition called post-diverticulitis irritable bowel syndrome, and that patients had anxiety and depression long after the initial attack. However, that study was based on a database of more than 1,000 patients and did not draw from personal testimonials from people living with diverticulitis.

In the latest research, patients described feelings of fear, anxiety and depression, and said they had been stigmatized for having the condition. Interviewees also said they live in constant fear of having another attack, are scared to travel and feel socially isolated. In addition, many patients continue to experience bothersome physical symptoms such as bloating, watery stools, abdominal pain, incomplete evacuation and nausea.

"We dug deeper into identifying the chronic physical, emotional and behavioral symptoms that can profoundly change people's lives after an attack of diverticulitis," said Spiegel, a professor of medicine at the David Geffen School of Medicine at UCLA and the Fielding School of Public Health. "Our findings reveal that many people suffer silently with severe quality-of-life problems long after an acute diverticulitis attack."

The researchers used those insights to develop a questionnaire to help doctors better assess the long-term impact of diverticulitis, which ultimately could lead to better understanding and management of the disease.

"Doctors often don't know to ask about these ongoing symptoms," Spiegel said. "We hope that our findings and new tool will help physicians better tailor individual treatment and reassure patients that they aren't alone."

To help them develop the new screening tool, researchers reviewed literature on quality-of-life measures used to gauge diverticulitis and related gastrointestinal conditions, and they interviewed experts and conducted focus groups with people who had suffered diverticulitis attacks. The team then developed a framework for the tool based on the most commonly described physical, social and psychological symptoms.

The researchers created a draft survey and tested it on 197 patients who had reported symptoms after an acute diverticulitis attack. Then, using feedback from those patients, the team refined the survey to create the final 24-question version.

"This new screening tool will help clinicians better define and manage diverticulitis," said study author Mark Reid, principal statistician at the UCLA/VA Center for Outcomes Research and Education. "We can now screen patients for poor quality of life based on their condition and then actively manage their diverticulitis like other chronic gastrointestinal conditions."

Spiegel said that more study is needed to help researchers understand how diverticulitis can trigger the longer-lasting symptoms.

INFORMATION:

The study was funded by Shire Pharmaceuticals.

Rachel Champeau (rchampeau@mednet.ucla.edu) (310) 794-2270

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

Finding quantum lines of desire

2014-07-30

Groundskeepers and landscapers hate them, but there is no fighting them. Called desire paths, social trails or goat tracks, they are the unofficial shortcuts people create between two locations when the purpose-built path doesn't take them where they want to go.

There's a similar concept in classical physics called the "path of least action." If you throw a softball to a friend, the ball traces a parabola through space. It doesn't follow a serpentine path or loop the loop because those paths have higher "actions" than the true path.

But what paths do quantum particles, ...

Tidal forces gave moon its shape, according to new analysis

2014-07-30

The shape of the moon deviates from a simple sphere in ways that scientists have struggled to explain. A new study by researchers at UC Santa Cruz shows that most of the moon's overall shape can be explained by taking into account tidal effects acting early in the moon's history.

The results, published July 30 in Nature, provide insights into the moon's early history, its orbital evolution, and its current orientation in the sky, according to lead author Ian Garrick-Bethell, assistant professor of Earth and planetary sciences at UC Santa Cruz.

As the moon cooled and ...

Target growth-driving cells within tumors, not fastest-proliferating cells

2014-07-30

BOSTON –– Of the many sub-groups of cells jockeying for supremacy within a cancerous tumor, the most dangerous may not be those that can proliferate the fastest, researchers at Dana-Farber Cancer Institute report in a paper appearing in an advance online publication of the journal Nature. The findings have important implications for the treatment of cancer with precision medicines, the study authors explained: Doctors need to ascertain which cell subgroups are truly driving the tumor's growth and metastasis and select drugs that target the critical genes within those cells. ...

ALMA finds double star with weird and wild planet-forming discs

2014-07-30

BOWLING GREEN, O.—From movies to television, obesity is still considered "fair game" for jokes and ridicule. A new study from researchers at Bowling Green State University took a closer look at weight-related humor to see if anti-fat attitudes played into a person's appreciation or distaste for fat humor in the media.

"Weight-Related Humor in the Media: Appreciation, Distaste and Anti-Fat Attitudes," by psychology Ph.D. candidate Jacob Burmeister and Dr. Robert Carels, professor of psychology, is featured in the June issue of Psychology of Popular Media Culture.

Carels ...

Innovative scientists update old-school pipetting with new-age technology

2014-07-30

CAMBRIDGE, Mass. (July 30, 2014) A team of Whitehead Institute researchers is bringing new levels of efficiency and accuracy to one of the most essential albeit tedious tasks of bench science: pipetting. And, in an effort to aid the scientific community at large, the group has established an open source system that enables anyone to benefit from this development free of charge.

Dubbed "iPipet," the system converts an iPad or any tablet computer into a "smart bench" that guides the execution of complex pipetting protocols. iPipet users can also share their pipetting designs ...

Mapping the optimal route between 2 quantum states

2014-07-30

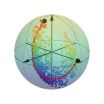

As a quantum state collapses from a quantum superposition to a classical state or a different superposition, it will follow a path known as a quantum trajectory. For each start and end state there is an optimal or "most likely" path, but it is not as easy to predict the path or track it experimentally as a straight-line between two points would be in our everyday, classical world.

In a new paper featured this week on the cover of Nature, scientists from the University of Rochester, University of California at Berkeley and Washington University in St. Louis have shown ...

Young binary star system may form planets with weird and wild orbits

2014-07-30

Unlike our solitary Sun, most stars form in binary pairs -- two stars that orbit a common center of mass. Though remarkably plentiful, binaries pose a number of questions, including how and where planets form in such complex environments.

While surveying a series of binary stars with the Atacama Large Millimeter/submillimeter Array (ALMA), astronomers uncovered a striking pair of wildly misaligned planet-forming disks in the young binary star system HK Tau. These results provide the clearest picture ever of protoplanetary disks around a double star and could reveal important ...

Scientists reproduce evolutionary changes by manipulating embryonic development of mice

2014-07-30

A group of researchers from the University of Helsinki and the Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona have been able experimentally to reproduce in mice morphological changes which have taken millions of years to occur. Through small and gradual modifications in the embryonic development of mice teeth, induced in the laboratory, scientists have obtained teeth which morphologically are very similar to those observed in the fossil registry of rodent species which separated from mice millions of years ago.

To modify the development of their teeth, the team from the Institute ...

Conservation scientists asking wrong questions on climate change impacts on wildlife

2014-07-30

Scientists studying the potential effects of climate change on the world's animal and plant species are focusing on the wrong factors, according to a new paper by a research team from the Wildlife Conservation Society, University of Queensland, and other organizations. The authors claim that most of the conservation science is missing the point when it comes to climate change.

While the majority of climate change scientists focus on the "direct" threats of changing temperatures and precipitation after 2031, far fewer researchers are studying how short-term human adaptation ...

Antarctic ice sheet is result of CO2 decrease, not continental breakup

2014-07-30

DURHAM, N.H. – Climate modelers from the University of New Hampshire have shown that the most likely explanation for the initiation of Antarctic glaciation during a major climate shift 34 million years ago was decreased carbon dioxide (CO2) levels. The finding counters a 40-year-old theory suggesting massive rearrangements of Earth's continents caused global cooling and the abrupt formation of the Antarctic ice sheet. It will provide scientists insight into the climate change implications of current rising global CO2 levels.

In a paper published today in Nature, Matthew ...

LAST 30 PRESS RELEASES:

ESC launches guidelines for patients to empower women with cardiovascular disease to make informed pregnancy health decisions

Towards tailor-made heat expansion-free materials for precision technology

New research delves into the potential for AI to improve radiology workflows and healthcare delivery

Rice selected to lead US Space Force Strategic Technology Institute 4

A new clue to how the body detects physical force

Climate projections warn 20% of Colombia’s cocoa-growing areas could be lost by 2050, but adaptation options remain

New poll: American Heart Association most trusted public health source after personal physician

New ethanol-assisted catalyst design dramatically improves low-temperature nitrogen oxide removal

New review highlights overlooked role of soil erosion in the global nitrogen cycle

Biochar type shapes how water moves through phosphorus rich vegetable soils

Why does the body deem some foods safe and others unsafe?

Report examines cancer care access for Native patients

New book examines how COVID-19 crisis entrenched inequality for women around the world

Evolved robots are born to run and refuse to die

Study finds shared genetic roots of MS across diverse ancestries

Endocrine Society elects Wu as 2027-2028 President

Broad pay ranges in job postings linked to fewer female applicants

How to make magnets act like graphene

The hidden cost of ‘bullshit’ corporate speak

Greaux Healthy Day declared in Lake Charles: Pennington Biomedical’s Greaux Healthy Initiative highlights childhood obesity challenge in SWLA

Into the heart of a dynamical neutron star

The weight of stress: Helping parents may protect children from obesity

Cost of physical therapy varies widely from state-to-state

Material previously thought to be quantum is actually new, nonquantum state of matter

Employment of people with disabilities declines in february

Peter WT Pisters, MD, honored with Charles M. Balch, MD, Distinguished Service Award from Society of Surgical Oncology

Rare pancreatic tumor case suggests distinctive calcification patterns in solid pseudopapillary neoplasms

Tubulin prevents toxic protein clumps in the brain, fighting back neurodegeneration

Less trippy, more therapeutic ‘magic mushrooms’

Concrete as a carbon sink

[Press-News.org] Diverticulitis patients reveal psychological, physical symptoms long after acute attacksFindings of UCLA study could lead to better disease management