(Press-News.org) Fortunately, you are not always what you eat – at least in Canada's Arctic.

New research from the University of Guelph reveals that arctic mammals such as caribou can metabolize some current-use pesticides (CUPs) ingested in vegetation.

This limits exposures in animals that consume the caribou – including humans.

"This is good news for the wildlife and people of the Arctic who survive by hunting caribou and other animals," said Adam Morris, a PhD student in the School of Environmental Sciences and lead author of the study published recently in Environmental Toxicology & Chemistry.

"The lack of any significant biomagnification through the food chain indicates that there is very little risk of harm from exposure to these CUPs in this region."

Pesticides or heavy metals enter rivers or lakes and vegetation, where they are ingested by fish and mammals and, in turn, are consumed by other animals and humans. The substances can become biomagnified, or concentrated in tissues and internal organs, as they move up the food chain.

Biomagnification has been implicated as the cause of higher concentrations of many long-used pesticides and other toxic chemicals such as PCBs found in wildlife and in Inuit and other aboriginal and non-aboriginal Northerners dependent on hunting, Morris said.

Such "legacy contaminants" are now widely banned under the Stockholm Convention, he said. But some have been replaced by CUPs, and few studies have looked at whether they also biomagnify.

Morris focused on studying the Bathurst region of the Canadian Arctic, working with Guelph toxicology professor emeritus Keith Solomon, adjunct professor Derek Muir, and collaborators from Environment Canada's Aquatic Contaminants Research Division.

They examined the vegetation-caribou-wolf food chain in the area, where the presence of other organic contaminants such as legacy pesticides and fluorinated surfactants suggested that CUPs might be found in the vegetation and animals.

Caribou are among the most important subsistence animals for people living in the North, and the Bathurst caribou herd is particularly critical to the area's socioeconomic security.

Wolves, like people, are a top "consumer" of caribou.

"It is an important responsibility, both for health and for food security issues that Northerner's face, that we monitor traditional food sources," Morris said.

By testing vegetation, the researchers found large enough concentrations of CUPs to confirm that they were entering the food chain.

In caribou eating that vegetation, CUPs were also present, but they did not increase (biomagnify) significantly in caribou compared to their diet. The concentrations were even lower in wolves, suggesting sufficient metabolism of CUPs in both animals to prevent significant biomagnification.

"The lack of biomagnification also means that we are unlikely to see sudden unexpected increases in concentrations of the CUPs in terrestrial top predators," he said.

"But this needs to be confirmed in other food chains in the Arctic before general trends can be established that are applicable to larger data sets."

Morris said these CUPs represent only a small percentage of contaminants in Arctic regions or in the environment globally.

"However, their unique set of properties does help us more clearly see how different contaminants behave in the environment and in food chains compared to legacy contaminants."

Morris has widened his research to include marine food chains and is also studying the effects of a range of organic flame retardants on the same terrestrial food chain.

The animal samples used in the research were all provided by subsistence hunters and trappers. "There would be no study possible, at all, without their co-operation," Morris said.

"I cannot stress enough how important local skills and knowledge were to this project. Generations of experience and knowledge often go into the hunts, and we simply cannot find that anywhere else in the world."

INFORMATION: END

Study: arctic mammals can metabolize some pesticides, limits human exposure

2014-08-06

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

New material structures bend like microscopic hair

2014-08-06

CAMBRIDGE, MA -- MIT engineers have fabricated a new elastic material coated with microscopic, hairlike structures that tilt in response to a magnetic field. Depending on the field's orientation, the microhairs can tilt to form a path through which fluid can flow; the material can even direct water upward, against gravity.

Each microhair, made of nickel, is about 70 microns high and 25 microns wide — about one-fourth the diameter of a human hair. The researchers fabricated an array of the microhairs onto an elastic, transparent layer of silicone.

In experiments, the ...

Coping skills help women overcome the mental anguish of unwanted body evaluation and sexual advances

2014-08-06

Some young women simply have more resilience and better coping skills and can shrug off the effect of unwanted cat calls, demeaning looks and sexual advances. Women with low resilience struggle and could develop psychological problems when they internalize such behavior, because they think they are to blame. So say Dawn Szymanski and Chandra Feltman of the University of Tennessee in the US, in Springer's journal Sex Roles, after studying how female college students handle the sexually objectifying behavior of men.

According to the popular feminist Objectification Theory, ...

Curing arthritis in mice

2014-08-06

Rheumatoid arthritis is a condition that causes painful inflammation of several joints in the body. The joint capsule becomes swollen, and the disease can also destroy cartilage and bone as it progresses. Rheumatoid arthritis affects 0.5% to 1% of the world's population. Up to this point, doctors have used various drugs to slow or stop the progression of the disease. But now, ETH Zurich researchers have developed a therapy that takes the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis in mice to a new level: after receiving the medication, researchers consider the animals to be fully ...

Job insecurity in academia harms the mental wellbeing of non-tenure track faculty

2014-08-06

Non-tenure-track academics experience stress, anxiety, and depression due to their insecure job situation, according to the first survey of its kind published in the open-access journal Frontiers in Psychology.

There were 1.4 contingent faculty workers in the USA, according to a report by the American Association of University Professors. These faculty members, such as research adjunct faculty, lecturers and instructors, are off the so-called "tenure track". They work under short-term contracts with limited health and retirement benefits, often part-time and at different ...

Preparing for a changing climate: Ecologists unwrap the science in the National Climate Change Assessment

2014-08-06

Two Ignite sessions focusing on findings in the United States National Climate Assesment5 (NCA) will take place on Monday, August 11th during the Ecological Society of America's 99th Annual Meeting, held this year in Sacramento, California.

The first session, Ignite 1: From Plains to Oceans to Islands: Regional Findings from the Third National Climate Assessment will highlight major findings from the report about the regional effects of climate change, discuss impacts to the ecosystems of the region, and explore how changes in those ecosystems can moderate or exacerbate ...

Triangulum galaxy snapped by VST

2014-08-06

Messier 33, otherwise known as NGC 598, is located about three million light-years away in the small northern constellation of Triangulum (The Triangle). Often known as the Triangulum Galaxy it was observed by the French comet hunter Charles Messier in August 1764, who listed it as number 33 in his famous list of prominent nebulae and star clusters. However, he was not the first to record the spiral galaxy; it was probably first documented by the Sicilian astronomer Giovanni Battista Hodierna around 100 years earlier.

Although the Triangulum Galaxy lies in the northern ...

Study: Many cancer survivors smoke years after diagnosis

2014-08-06

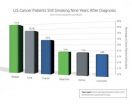

ATLANTA – August 6, 2014–Nearly one in ten cancer survivors reports smoking many years after a diagnosis, according to a new study by American Cancer Society researchers. Further, among ten cancer sites included in the analysis, the highest rates of smoking were in bladder and lung cancers, two sites strongly associated with smoking. The study appears early online in Cancer Epidemiology, Biomarkers & Prevention.

Cigarette smoking decreases the effectiveness of cancer treatments, increases the probability of recurrence, and reduces survival time. Nonetheless, some studies ...

Nearly 10 percent of patients with cancer still smoke

2014-08-06

PHILADELPHIA — Nine years after diagnosis, 9.3 percent of U.S. cancer survivors were current smokers and 83 percent of these individuals were daily smokers who averaged 14.7 cigarettes per day, according to a report in Cancer Epidemiology, Biomarkers & Prevention, a journal of the American Association for Cancer Research (AACR).

"We need to follow up with cancer survivors long after their diagnoses to see whether they are still smoking and offer appropriate counseling, interventions, and possible medications to help them quit," said Lee Westmaas, PhD, director of tobacco ...

Healthy diet set early in life

2014-08-06

Promoting a healthy diet from infancy is important to prevent childhood obesity and the onset of chronic disease.

This is the finding from a study published in the latest issue of Australian and New Zealand Journal of Public Health.

Led by Rebecca Byrne from QUT, the study described quantity and diversity of food and drinks consumed by children aged 12-16 months.

"The toddler years are a critical age in the development of long-term food preferences, but this is also the age that autonomy, independence and food fussiness begins," Ms Byrne said.

"Childhood obesity in ...

Nutrition an issue for Indigenous Australians

2014-08-06

Nutrition has not been given enough priority in national Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander health policy in recent years.

This is the finding from a study published in the latest issue of Australian and New Zealand Journal of Public Health.

Led by Jennifer Browne from La Trobe University, the study examined Aboriginal-specific health policies and strategies developed between 2000 and 2012.

"Increased inclusion of nutrition in Aboriginal health policy was identified during the first half of this period, but less during the second where a much greater emphasis was ...