(Press-News.org) Cambridge, MA, Aug 6 - A series of studies begun by Harvard Stem Cell Institute (HSCI) scientists eight years ago has lead to a report published today that may be a major step forward in the quest to develop real treatments for amyotrophic lateral sclerosis, ALS, or Lou Gehrig's disease.

The findings by Harvard professor of Stem Cell and Regenerative Biology (HSCRB) Kevin Eggan and colleagues also has produced functionally identical results in human motor neurons in a laboratory dish and in a mouse model of the disease, demonstrating that the modeling of human disease with customized stem cells in the laboratory could someday relatively soon eliminate some of the need for animal testing.

The new study, published today in Science Translational Medicine, suggest that compounds already in clinical trials for other purposes may be promising candidate therapeutics for ALS. The Harvard authors found that genetically intervening in the pathway these drugs act on increased survival time of an ALS animal model 5-10 percent, and while that is a long way from curing the universally fatal neurodegenerative disease, "any ALS patient would be excited about this extended life span," said Eggan, who pioneered the disease in a dish concept.

Sophie De Boer, a graduate student in Eggan's lab, is the first author on the Science Translational Medicine paper.

This latest finding is expected to push towards clinical studies the second major ALS discovery from Eggan's lab in less than a year. The HSCI stem cell biologist, and his neuroscience and neurology collaborators at Massachusetts General Hospital and Boston Children's Hospital, are preparing for a phase I clinical trial of a medication already approved for epilepsy which Eggan and colleagues discovered quiets disease related electrical excitability in the motor neurons effected in ALS.

In a paper in 2007, Eggan and colleagues demonstrated that glial cells, background cells in the nervous system, were involved in motor neuron degeneration in a mouse model of ALS. And the following year the researchers reported that the same thing was happening in human motor neurons made from patient stem cells, and proposed that prostanoid molecules, a group of substances involved in inflammation in everything from pain to pregnancy, might be playing a role in the glial cells.

Today the researchers reported they have confirmed there is a change in prostanoid receptors in the gial cells playing a role in ALS, and with genetic and chemical experiments they showed that this is playing a role in ALS. They further report that when the effected receptor is blocked, the ALS damage done by the glial cells is reduced.

This latest work, says Eggan, first done in human motor neurons in a dish, and then in a mouse model of ALS, "says that indeed this stem cell model was predictive of something that can happen inside a whole animal, and its important because it demonstrates that this is really an important target for an ALS therapeutic. If we can inhibit this receptor in an ALS patient, we might slow down the progression of the disease, and that would be a huge step."

Eggan said "one feature of the glial cells in ALS that attack motor neurons is that they have higher expression of this prostanoid receptor. Removing just one of the two copies of the receptor in the glial cells had an effect on extending the life span" of the ALS mice," Eggan said, and "inhibition by a drug is unlikely to have an effect as complete as a knockout in the mice."

Eggan said that experiments on human stem cell-generated ALS motor neurons also show that "if we inhibit that receptor in the ALS cells with a chemical, those cells lose their toxicity to motor neurons

"This is a very exciting period for those whose lives are threatened by ALS, and it is exciting for my lab," Eggan said. "First we recently identified a pathway that we think is important for degeneration inside the motor neuron, and now we've found this pathway in cells outside the motor neuron. This has potential to have a very substantial effect on what's happening in ALS."

The research was funded by Project ALS, the New York Stem Cell Foundation, P2ALS, and the Howard Hughes Medical Institute.

INFORMATION:

Contact:

B. D. Colen

bd_colen@harvard.edu

617-495-7821 / / 617-413-1224 - cell

HSCI researchers identify another potential ALS treatment avenue

Similar results in experimental animals and human cells in dish

2014-08-06

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

Dr. Brenna Anderson publishes commentary in BJOG

2014-08-06

Brenna Anderson, MD, of the Division of Maternal-Fetal Medicine at Women & Infants of Rhode Island and an associate professor of obstetrics and gynecology at The Warren Alpert Medical School of Brown University, has published a commentary in the current issue of BJOG: An International Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology, now available online. The commentary is entitled "The time has come to consider neonatal outcomes when designing embryo transfer policies."

Dr. Anderson offers her commentary in response to an article in the same issue by Kamphius et al. in which the ...

Brain tumors fly under the body's radar like stealth jets, new U-M research suggests

2014-08-06

ANN ARBOR, Mich. — Brain tumors fly under the radar of the body's defense forces by coating their cells with extra amounts of a specific protein, new research shows.

Like a stealth fighter jet, the coating means the cells evade detection by the early-warning immune system that should detect and kill them. The stealth approach lets the tumors hide until it's too late for the body to defeat them.

The findings, made in mice and rats, show the key role of a protein called galectin-1 in some of the most dangerous brain tumors, called high grade malignant gliomas. A research ...

NIST ion duet offers tunable module for quantum simulator

2014-08-06

BOULDER, Colo -- Physicists at the National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST) have demonstrated a pas de deux of atomic ions that combines the fine choreography of dance with precise individual control.

NIST's ion duet, described in the August 7 issue of Nature, is a component for a flexible quantum simulator that could be scaled up in size and configured to model quantum systems of a complexity that overwhelms traditional computer simulations. Beyond simulation, the duet might also be used to perform logic operations in future quantum computers, or as a quantum-enhanced ...

Stowers researchers reveal molecular competition drives adult stem cells to specialize

2014-08-06

KANSAS CITY, MO — Adult organisms ranging from fruit flies to humans harbor adult stem cells, some of which renew themselves through cell division while others differentiate into the specialized cells needed to replace worn-out or damaged organs and tissues.

Understanding the molecular mechanisms that control the balance between self-renewal and differentiation in adult stem cells is an important foundation for developing therapies to regenerate diseased, injured or aged tissue.

In the current issue of the journal Nature, scientists at the

Stowers Institute for ...

Enhanced international cooperation needed in Antarctica

2014-08-06

Countries need to work together to ensure Antarctic research continues and key questions on the region are answered, researchers say.

In an article published in Nature this week, 75 scientists along with policy makers in 22 countries have outlined what they see as the major priorities for Antarctic research over the next 20 years and beyond.

In it they outline six priorities for Antarctic science – the most important scientific questions to be addressed in the region, as well as what they think is needed to achieve them.

One of the report's lead authors, Monash University ...

Mercury in the global ocean

2014-08-06

Although the days of odd behavior among hat makers are a thing of the past, the dangers mercury poses to humans and the environment persist today.

Mercury is a naturally occurring element as well as a by-product of such distinctly human enterprises as burning coal and making cement. Estimates of "bioavailable" mercury—forms of the element that can be taken up by animals and humans—play an important role in everything from drafting an international treaty designed to protect humans and the environment from mercury emissions, to establishing public policies behind warnings ...

Farm manager plays leading role in postharvest loss

2014-08-06

URBANA, Ill. – With all the effort it takes to grow a food crop from seed to sale, it may be surprising that some farms in Brazil lose 10 to 12 percent of their yield at various points along the postharvest route. According to a University of Illinois agricultural economist, when it comes to meeting the needs of the world's growing population that's a lot of food falling through the cracks. Interestingly, farm managers who are aware of the factors that contribute to postharvest grain loss actually lose less grain. This was one of the findings in a study that examined how ...

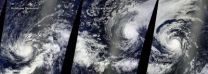

NASA satellite paints a triple hurricane Pacific panorama

2014-08-06

In three passes over the Central and Eastern Pacific Ocean, NASA's Terra satellite took pictures of the three current tropical cyclones, painting a Pacific Tropical Panorama. Terra observed Hurricane Genevieve, Hurricane Iselle and Hurricane Julio in order from west to east. Iselle has now triggered a tropical storm watch in Hawaii.

The Moderate Resolution Imaging Spectroradiometer or MODIS instrument is a key instrument aboard NASA's Terra and Aqua satellites. Between the two satellites, MODIS instruments view the entire surface of the Earth every one to two days. When ...

Most kids with blunt torso trauma can skip the pelvic X-ray

2014-08-06

WASHINGTON – Pelvic x-rays ordered as a matter of course for children who have suffered blunt force trauma do not accurately identify all cases of pelvic fractures or dislocations and are usually unnecessary for patients for whom abdominal/pelvic CT scanning is otherwise planned. A study published online in Annals of Emergency Medicine last week casts doubt on a practice that has been recommended by the Advanced Trauma Life Support Program (ATLS), considered the gold standard for trauma patients "(Sensitivity of Plain Pelvis Radiography in Children with Blunt Torso Trauma). ...

Scientists discover how 'jumping genes' help black truffles adapt to their environment

2014-08-06

Black truffles, also known as Périgord truffles, grow in symbiosis with the roots of oak and hazelnut trees. In the world of haute cuisine, they are expensive and highly prized.

In the world of epigenetics, however, the fungi (Tuber melanosporum) are of major interest for another reason: their unique pattern of DNA methylation, a biochemical process that chemically modifies nucleic acids without changing their sequence. Epigenetics is the study of changes in gene expression caused by mechanisms other than changes in the DNA sequence.

A newly published study in the journal ...

LAST 30 PRESS RELEASES:

COVID-19 vaccination during pregnancy may help prevent preeclampsia

Menopausal hormone therapy not linked to increased risk of death

Chronic shortage of family doctors in England, reveals BMJ analysis

Booster jabs reduce the risks of COVID-19 deaths, study finds

Screening increases survival rate for stage IV breast cancer by 60%

ACC announces inaugural fellow for the Thad and Gerry Waites Rural Cardiovascular Research Fellowship

University of Oklahoma researchers develop durable hybrid materials for faster radiation detection

Medicaid disenrollment spikes at age 19, study finds

Turning agricultural waste into advanced materials: Review highlights how torrefaction could power a sustainable carbon future

New study warns emerging pollutants in livestock and aquaculture waste may threaten ecosystems and public health

Integrated rice–aquatic farming systems may hold the key to smarter nitrogen use and lower agricultural emissions

Hope for global banana farming in genetic discovery

Mirror image pheromones help beetles swipe right

Prenatal lead exposure related to worse cognitive function in adults

Research alert: Understanding substance use across the full spectrum of sexual identity

Pekingese, Shih Tzu and Staffordshire Bull Terrier among twelve dog breeds at risk of serious breathing condition

Selected dog breeds with most breathing trouble identified in new study

Interplay of class and gender may influence social judgments differently between cultures

Pollen counts can be predicted by machine learning models using meteorological data with more than 80% accuracy even a week ahead, for both grass and birch tree pollen, which could be key in effective

Rewriting our understanding of early hominin dispersal to Eurasia

Rising simultaneous wildfire risk compromises international firefighting efforts

Honey bee "dance floors" can be accurately located with a new method, mapping where in the hive forager bees perform waggle dances to signal the location of pollen and nectar for their nestmates

Exercise and nutritional drinks can reduce the need for care in dementia

Michelson Medical Research Foundation awards $750,000 to rising immunology leaders

SfN announces Early Career Policy Ambassadors Class of 2026

Spiritual practices strongly associated with reduced risk for hazardous alcohol and drug use

Novel vaccine protects against C. diff disease and recurrence

An “electrical” circadian clock balances growth between shoots and roots

Largest study of rare skin cancer in Mexican patients shows its more complex than previously thought

Colonists dredged away Sydney’s natural oyster reefs. Now science knows how best to restore them.

[Press-News.org] HSCI researchers identify another potential ALS treatment avenueSimilar results in experimental animals and human cells in dish