(Press-News.org) Although the days of odd behavior among hat makers are a thing of the past, the dangers mercury poses to humans and the environment persist today.

Mercury is a naturally occurring element as well as a by-product of such distinctly human enterprises as burning coal and making cement. Estimates of "bioavailable" mercury—forms of the element that can be taken up by animals and humans—play an important role in everything from drafting an international treaty designed to protect humans and the environment from mercury emissions, to establishing public policies behind warnings about seafood consumption.

Yet surprisingly little is known about how much mercury in the environment is the result of human activity, or even how much bioavailable mercury exists in the global ocean. Until now.

A new paper by a group that includes researchers from the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution (WHOI), Wright State University, Observatoire Midi-Pyréneés in France, and the Royal Netherlands Institute for Sea Research appears in this week's edition of the journal Nature and provides the first direct calculation of mercury in the global ocean from pollution based on data obtained from 12 sampling cruises over the past 8 years. The work, which was funded by the U.S. National Science Foundation and the European Research Council and led by WHOI marine chemist Carl Lamborg, also provides a look at the global distribution of mercury in the marine environment.

"It would seem that, if we want to regulate the mercury emissions into the environment and in the food we eat, then we should first know how much is there and how much human activity is adding every year," said Lamborg, who has been studying mercury for 24 years. "At the moment, however, there is no way to look at a water sample and tell the difference between mercury that came from pollution and mercury that came from natural sources. Now we have a way to at least separate the bulk contributions of natural and human sources over time."

The group started by looking at data sets that offer detail about oceanic levels of phosphate, a substance that is both better studied than mercury and that behaves in much the same way in the ocean. Phosphate is a nutrient that, like mercury, is taken up into the marine food web by binding with organic material. By determining the ratio of phosphate to mercury in water deeper than 1,000 meters (3,300 feet) that has not been in contact with Earth's atmosphere since the Industrial Revolution, the group was able to estimate mercury in the ocean that originated from natural sources such as the breakdown, or "weathering," of rocks on land.

Their findings agreed with what they would expect to see given the known pattern of global ocean circulation. North Atlantic waters, for example, showed the most obvious signs of mercury from pollution because that is where surface waters sink under the influence of temperature and salinity changes to form deep and intermediate water flows. The Tropical and Northeast Pacific, on the other hand, were seen to be relatively unaffected because it takes centuries for deep ocean water to circulate to those regions.

But determining the contribution of mercury from human activity required another step. To obtain estimates for shallower waters and to provide basin-wide numbers for the amount of mercury in the global ocean, the team needed a tracer—a substance that could be linked back to the major activities that release mercury into the environment in the first place. They found it in one of the most well studied gases of the past 40 years—carbon dioxide. Databases of CO2 in ocean waters are extensive and readily available for every ocean basin at virtually all depths. Because much of the mercury and CO2 from human sources derive from the same activities, the team was able to derive an index relating the two and use it to calculate the amount and distribution of mercury in the world's ocean basins that originated from human activity.

Analysis of their results showed rough agreement with the models used previously—that the ocean contains about 60,000 to 80,000 tons of pollution mercury. In addition, they found that ocean waters shallower than about 100 m (300 feet) have tripled in mercury concentration since the Industrial Revolution and that the ocean as a whole has shown an increase of roughly 10 percent over pre-industrial mercury levels.

"With the increases we've seen in the recent past, the next 50 years could very well add the same amount we've seen in the past 150," said Lamborg. "The trouble is, we don't know what it all means for fish and marine mammals. It likely means some fish also contain at least three times more mercury than 150 years ago, but it could be more. The key is now we have some solid numbers on which to base continued work."

"Mercury is a priority environmental poison detectable wherever we look for it, including the global ocean abyss," says Don Rice, director of the National Science Foundation (NSF)'s Chemical Oceanography Program, which funded the research. "These scientists have reminded us that the problem is far from abatement, especially in regions of the world ocean where the human fingerprint is most distinct."

INFORMATION:

The Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution is a private, independent organization on Cape Cod, Mass., dedicated to marine research, engineering, and higher education. Established in 1930 on a recommendation from the National Academy of Sciences, its primary mission is to understand the ocean and its interaction with the Earth as a whole, and to communicate a basic understanding of the ocean's role in the changing global environment. For more information, please visit http://www.whoi.edu.

Mercury in the global ocean

Study shows three times more mercury in upper ocean since the Industrial Revolution

2014-08-06

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

Farm manager plays leading role in postharvest loss

2014-08-06

URBANA, Ill. – With all the effort it takes to grow a food crop from seed to sale, it may be surprising that some farms in Brazil lose 10 to 12 percent of their yield at various points along the postharvest route. According to a University of Illinois agricultural economist, when it comes to meeting the needs of the world's growing population that's a lot of food falling through the cracks. Interestingly, farm managers who are aware of the factors that contribute to postharvest grain loss actually lose less grain. This was one of the findings in a study that examined how ...

NASA satellite paints a triple hurricane Pacific panorama

2014-08-06

In three passes over the Central and Eastern Pacific Ocean, NASA's Terra satellite took pictures of the three current tropical cyclones, painting a Pacific Tropical Panorama. Terra observed Hurricane Genevieve, Hurricane Iselle and Hurricane Julio in order from west to east. Iselle has now triggered a tropical storm watch in Hawaii.

The Moderate Resolution Imaging Spectroradiometer or MODIS instrument is a key instrument aboard NASA's Terra and Aqua satellites. Between the two satellites, MODIS instruments view the entire surface of the Earth every one to two days. When ...

Most kids with blunt torso trauma can skip the pelvic X-ray

2014-08-06

WASHINGTON – Pelvic x-rays ordered as a matter of course for children who have suffered blunt force trauma do not accurately identify all cases of pelvic fractures or dislocations and are usually unnecessary for patients for whom abdominal/pelvic CT scanning is otherwise planned. A study published online in Annals of Emergency Medicine last week casts doubt on a practice that has been recommended by the Advanced Trauma Life Support Program (ATLS), considered the gold standard for trauma patients "(Sensitivity of Plain Pelvis Radiography in Children with Blunt Torso Trauma). ...

Scientists discover how 'jumping genes' help black truffles adapt to their environment

2014-08-06

Black truffles, also known as Périgord truffles, grow in symbiosis with the roots of oak and hazelnut trees. In the world of haute cuisine, they are expensive and highly prized.

In the world of epigenetics, however, the fungi (Tuber melanosporum) are of major interest for another reason: their unique pattern of DNA methylation, a biochemical process that chemically modifies nucleic acids without changing their sequence. Epigenetics is the study of changes in gene expression caused by mechanisms other than changes in the DNA sequence.

A newly published study in the journal ...

Wiki ranking

2014-08-06

Wikipedia the free, online collaborative encyclopedia is an important source of information. However, while the team of volunteer editors endeavors to maintain high standards, there are occasionally problems with the veracity of content, deliberate vandalism and incomplete entries. Writing in the International Journal of Information Quality, computer scientists in China have devised a software algorithm that can automatically check a particular entry and rank it according to quality.

Jingyu Han and Kejia Chen of Nanjing University of Posts and Telecommunications, explain ...

A new way to model cancer

2014-08-06

CAMBRIDGE, MA -- Sequencing the genomes of tumor cells has revealed thousands of mutations associated with cancer. One way to discover the role of these mutations is to breed a strain of mice that carry the genetic flaw — but breeding such mice is an expensive, time-consuming process.

Now, MIT researchers have found an alternative: They have shown that a gene-editing system called CRISPR can introduce cancer-causing mutations into the livers of adult mice, enabling scientists to screen these mutations much more quickly.

In a study appearing in the August 6th issue of ...

Discovery yields master regulator of toxin production in staph infections

2014-08-06

St. Jude Children's Research Hospital scientists have discovered an enzyme that regulates production of the toxins that contribute to potentially life-threatening Staphylococcus aureus infections. The study recently appeared in the scientific journal the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (PNAS).

Researchers also showed that the same enzyme allows Staphylococcus aureus to use fatty acids acquired from the infected individual to make the membrane that bacteria need to grow and flourish. The results provide a promising focus for efforts to develop a much-needed ...

Pyrocumulonibus cloud rises up from Canadian wildfires

2014-08-06

The Northern Territories in Canada is experiencing one of its worst fire seasons in history. As of this date, there have been 344 wildfires that have burned 2,830,907 hectares of land (close to 7 million acres). The area around the Great Slave Lake, Yellowknife, Ft. Smith, and the Buffalo Lake have been plagued with uncontrolled fires all season long. This natural-color image collected by the Moderate Resolution Imaging Spectroradiometer (MODIS) aboard the Aqua satellite on August 05, 2014 shows a pyrocumulonimbus cloud erupting from the fire north of Buffalo Lake. It ...

A website to help safeguard the United States borders against alien scale insect pests

2014-08-06

Scales are small insects that feed by sucking plant juices. They can attack nearly any plant and cause serious damage to many agricultural and ornamental plants. While native scales have natural enemies that generally keep their populations in check, invasive species often do not, and for this reason many commercially important scale pests in the United States are species that were accidentally introduced.

In order to facilitate the identification of alien species at U.S. ports-of-entry, scientists of the United States Department of Agriculture and California Department ...

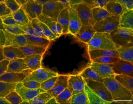

Discovery about wound healing key to understanding cell movement

2014-08-06

Research by a civil engineer from the University of Waterloo is helping shed light on the way wounds heal and may someday have implications for understanding how cancer spreads, as well as why certain birth defects occur.

Professor Wayne Brodland is developing computational models for studying the mechanical interactions between cells. In this project, he worked with a team of international researchers who found that the way wounds knit together is more complex than we thought. The results were published this week in the journal, Nature Physics.

"When people think ...

LAST 30 PRESS RELEASES:

Does a past abortion or miscarriage affect a woman’s risk of developing breast cancer?

Could a treatment redirect the body’s anti-viral immune response to target cancer cells?

How does universal, free prescription drug coverage affect older adults’ finances and behaviors?

Do certain factors affect life expectancy in people with spina bifida?

New study: Routine aspirin therapy prevents severe preeclampsia in at-risk populations

Afraid of chemistry at school? It’s not all the subject’s fault

How tech-dependency and pandemic isolation have created ‘anxious generation’

Nearly three quarters of US baby foods are ultra-processed, new study finds

Nonablative radiofrequency may improve sexual function in postmenopausal women

Pulsed dynamic water electrolysis: Mass transfer enhancement, microenvironment regulation, and hydrogen production optimization

Coordination thermodynamic control of magnetic domain configuration evolution toward low‑frequency electromagnetic attenuation

High‑density 1D ionic wire arrays for osmotic energy conversion

DAYU3D: A modern code for HTGR thermal-hydraulic design and accident analysis

Accelerating development of new energy system with “substance-energy network” as foundation

Recombinant lipidated receptor-binding domain for mucosal vaccine

Rising CO₂ and warming jointly limit phosphorus availability in rice soils

Shandong Agricultural University researchers redefine green revolution genes to boost wheat yield potential

Phylogenomics Insights: Worldwide phylogeny and integrative taxonomy of Clematis

Noise pollution is affecting birds' reproduction, stress levels and more. The good news is we can fix it.

Researchers identify cleaner ways to burn biomass using new environmental impact metric

Avian malaria widespread across Hawaiʻi bird communities, new UH study finds

New study improves accuracy in tracking ammonia pollution sources

Scientists turn agricultural waste into powerful material that removes excess nutrients from water

Tracking whether California’s criminal courts deliver racial justice

Aerobic exercise may be most effective for relieving depression/anxiety symptoms

School restrictive smartphone policies may save a small amount of money by reducing staff costs

UCLA report reveals a significant global palliative care gap among children

The psychology of self-driving cars: Why the technology doesn’t suit human brains

Scientists discover new DNA-binding proteins from extreme environments that could improve disease diagnosis

Rapid response launched to tackle new yellow rust strains threatening UK wheat

[Press-News.org] Mercury in the global oceanStudy shows three times more mercury in upper ocean since the Industrial Revolution