(Press-News.org) A protein present at high levels in more than half of all human cancers drives cell growth by blocking the expression of just a handful of genes involved in DNA packaging and cell death, according to a new study by researchers at the Stanford University School of Medicine.

The researchers found that the protein, called Myc, works through a tiny regulatory molecule called a microRNA to suppress the genes' expression. It marks the first time that a subset of Myc-controlled genes has been identified as critical players in the protein's cancer-causing function, and suggests new therapeutic targets for Myc-dependent cancers.

"This is a different way of thinking about the roles of microRNA and chromatin packaging in cancer," said Dean Felsher, MD, PhD, professor of oncology and of pathology. "We were very surprised to learn that the overexpression of one microRNA can mimic the cancerous effect of Myc."

Felsher is the senior author of the study, which will be published Aug. 11 in Cancer Cell. The lead author is instructor Yulin Li, MD, PhD.

The genes identified by the researchers produce proteins that govern whether a cell self-renews by dividing, enters a resting state called senescence or takes itself permanently out of commission through programmed cell suicide. Exquisite control of these processes is necessary to control or eliminate potentially dangerous tumor cells.

The gene encoding the Myc protein is a well-known and potent oncogene — a term used to describe genes that cause cancer when mutated or abnormally expressed. It regulates the expression of around 10,000 genes and microRNAs in a cell. Scientists have long known that inactivating Myc, or blocking its expression, can cause Myc-dependent cancer cells to stop growing or die, as well as cause tumor regression in mice with Myc-dependent solid cancers. This phenomenon of dependence is called oncogene addiction.

MicroRNAs are small RNA molecules (only about 22 nucleotides) that can, like Myc, regulate gene expression. Previous research had shown that Myc overexpression causes an increase in the levels of a family of microRNAs called miR-17-92.

"People have known for several years that Myc regulates the expression of microRNAs," said Felsher. "But it wasn't clear how this was related to Myc's oncogenic function."

Li found that Myc-dependent cancer cells — either grown in a laboratory dish or as a tumor in mice — in which miR-17-92 expression was locked in the "on" position kept dividing even when Myc expression was blocked. This suggested that Myc works through the microRNA family to exert its cancer-causing effects.

Li then looked for an overlap among genes affected by Myc overexpression and those affected by miR-17-92. Of these, the team found about 401 genes whose expression was either increased or suppressed by both Myc and miR-17-92. They chose to focus on genes that were suppressed because these genes exhibited on average many more binding sites for the microRNAs. They further winnowed their panel to 15 genes regulated by more than one miR-17-92 binding site.

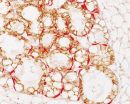

Of these, five stood out. Four encode proteins known to regulate how DNA is tightly packaged around proteins (creating a complex called chromatin). This packaging is necessary to allow the DNA to fit within a cell's nucleus, but it makes it difficult for proteins regulating transcription to access genes. The four proteins controlled by Myc and miR-17-92 affect cell proliferation and senescence by regulating gene accessibility within the chromatin. They had never before been identified as Myc or miR-17-92 targets.

The fifth encodes a protein called Bim that induces programmed cell death, or apoptosis. This cellular suicide pathway is used by the body to eliminate damaged or unneeded cells. Bim expression had been previously reported to be affected by miR-17-92.

Notably, all of the proteins are known to affect either cellular proliferation, entry into a resting state of the cell cycle or apoptosis, in part by granting or prohibiting access to genes in tightly packaged stretches of DNA in the chromatin.

"Myc is still a general amplifier of gene transcription and expression," said Felsher, "but our study shows that the maintenance of the cancerous state relies on a more-focused mechanism."

Finally, Li and his colleagues showed that suppressing the expression of the five target genes, effectively mimicking Myc overexpression, partially mitigates the effect of Myc deactivation. Up to 30 percent of Myc-dependent cancer cells in culture continued to grow (in contrast to only 11 percent of control cells) in the absence of Myc expression, and tumors in mice either failed to regress or recurred within a few weeks.

"One of the biggest unanswered questions in oncology is how oncogenes cause cancer, and whether you can replace an oncogene with another gene product," said Felsher. "These experiments begin to reveal how Myc affects the self-renewal decisions of cells. They may also help us target those aspects of Myc overexpression that contribute to the cancer phenotype."

INFORMATION:

Other Stanford co-authors of the paper are former postdoctoral scholar Peter Choi, PhD; postdoctoral scholar Stephanie Casey, PhD; and professor of computer science David Dill, PhD.

The research was supported by the National Institutes of Health (grants R01CA170378, U54CA149145, 1F32CA177139 and 5T32A107290), the Leukemia and Lymphoma Society and the King Abdullah University of Science and Technology.

Information about Stanford's Department of Medicine and Department of Pathology, both of which also supported the work, is available at http://medicine.stanford.edu and http://pathology.stanford.edu.

The Stanford University School of Medicine consistently ranks among the nation's top medical schools, integrating research, medical education, patient care and community service. For more news about the school, please visit http://mednews.stanford.edu. The medical school is part of Stanford Medicine, which includes Stanford Hospital & Clinics and Lucile Packard Children's Hospital Stanford. For information about all three, please visit http://stanfordmedicine.org/about/news.html.

Print media contact: Krista Conger at (650) 725-5371 (kristac@stanford.edu)

Broadcast media contact: M.A. Malone at (650) 723-6912 (mamalone@stanford.edu)

Stanford researchers uncover cancer-causing mechanism behind powerful human oncogene

2014-08-11

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

Blood cells are a new and unexpected source of neurons in crayfish

2014-08-11

Researchers have strived for years to determine how neurons are produced and integrated into the brain throughout adult life. In an intriguing twist, scientists reporting in the August 11 issue of the Cell Press journal Developmental Cell provide evidence that adult-born neurons are derived from a special type of circulating blood cell produced by the immune system. The findings—which were made in crayfish—suggest that the immune system may contribute to the development of the unknown role of certain brain diseases in the development of brain and other tissues.

In many ...

How breast cancer usurps the powers of mammary stem cells

2014-08-11

During pregnancy, certain hormones trigger specialized mammary stem cells to create milk-producing cells essential to lactation. Scientists at the University of California, San Diego School of Medicine and Moores Cancer Center have found that mammary stem cells associated with the pregnant mammary gland are related to stem cells found in breast cancer.

Writing in the August 11, 2014 issue of Developmental Cell, David A. Cheresh, PhD, Distinguished Professor of Pathology and vice-chair for research and development, Jay Desgrosellier, PhD, assistant professor of pathology ...

Malaria medicine chloroquine inhibits tumor growth and metastases

2014-08-11

A recent study by investigators at VIB and KU Leuven has demonstrated that chloroquine also normalizes the abnormal blood vessels in tumors. This blood vessel normalization results in an increased barrier function on the one hand -- thereby blocking cancer cell dissemination and metastasis -- and in enhanced tumor perfusion on the other hand, which increases the response of the tumor to chemotherapy.

The anti-cancer effect of the antimalarial agent chloroquine when combined with conventional chemotherapy has been well documented in experimental animal models. To date, ...

Climate change negatively impacting Great Lakes, GVSU researcher says

2014-08-11

MUSKEGON, Mich. -- Climate change is having a direct negative effect on the Great Lakes, including impacts to recreational value, drinking water potential, and becoming more suited to invasive species and infectious pathogens, according to a Grand Valley State University researcher.

The impact of climate change on the Great Lakes, as well as other natural resources in the United States, was explored in the report "Science, Education, and Outreach Roadmap for Natural Resources," recently released by the Association of Public and Land-grant Universities. Kevin Strychar, ...

CRI scientists pinpoint gene likely to promote childhood cancers

2014-08-11

DALLAS – Aug. 11, 2014 – Researchers at the Children’s Medical Center Research Institute at UT Southwestern (CRI) have identified a gene that contributes to the development of several childhood cancers, in a study conducted with mice designed to model the cancers. If the findings prove to be applicable to humans, the research could lead to new strategies for targeting certain childhood cancers at a molecular level. The study was published today in the journal Cancer Cell.

“We and others have found that Lin28b – a gene that is normally turned on in fetal but not adult ...

US immigration is associated with rise in smoking among Latinos and Asians

2014-08-11

Immigration to the U.S. may result in increased smoking in Latino and Asian women, according to new research from sociologists at Rice University, Duke University and the University of Southern California.

The study, "Gender, Acculturation and Smoking Behavior Among U.S. Asian and Latino Immigrants," examines smoking prevalence and frequency among Asian and Latino U.S. immigrants. The research focuses on how gender differences in smoking behavior are shaped by aspects of acculturation and the original decision to migrate. The study was published recently in the journal ...

Kessler Foundation researchers publish study on task constraint and task switching

2014-08-11

West Orange, NJ. August 11, 2014 -- Kessler Foundation scientists have published results of cognitive research that show the negative effects that unexpected task constraint, following self-generated task choice, has on task-switching performance. The article, "You can't always get what you want: The influence of unexpected task constraint on voluntary task switching", was published online on June 11 by The Quarterly Journal of Experimental Psychology (DOI:10.1080/17470218.2014.917115). The authors are Starla Weaver, PhD, and Glenn Wylie, DPhil, of Kessler Foundation, John ...

Study: 1 out of 5 adult orthopaedic trauma patients sought additional providers for narcotic prescriptions

2014-08-11

ROSEMONT, Ill.─"Doctor shopping," the growing practice of obtaining narcotic prescriptions from multiple providers, has led to measurable increases in drug use among postoperative trauma patients. The study, "Narcotic Use and Postoperative Doctor Shopping in the Orthopaedic Trauma Population," appearing in the August issue of the Journal of Bone & Joint Surgery (JBJS), links doctor shopping to higher narcotic use among orthopaedic patients. The data was presented earlier this year at the 2014 Annual Meeting of the American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons (AAOS).

"There ...

Keeping viruses at bay

2014-08-11

>

Our immunosensory system detects virus such as influenza via specific characteristics of viral ribonucleic acid. Previously, it was unclear how the immune system prevents viruses from simply donning molecular camouflage in order to escape detection. An international team of researchers from the University of Bonn Hospital and the London Research Institute have now discovered that our immunosensory system attacks viruses on a molecular level. In this way, a healthy organism can keep rotaviruses, a common cause of diarrheal epidemics, at bay. The results have been published ...

Fertile discovery

2014-08-11

Queen's University researcher Richard Oko and his co-investigators have come up with a promising method of treating male infertility using a synthetic version of the sperm-originated protein known as PAWP.

They found this protein is sufficient and required to initiate the fertilization process.

Dr. Oko's research promises to diagnose and treat cases of male factor infertility where a patient's sperm is unable to initiate or induce activation of the egg to form an early embryo.

"PAWP is able to induce embryo development in human eggs in a fashion similar to the natural ...