(Press-News.org) Scientists from Queen Mary University of London (QMUL) have discovered mutations in genes that lead to childhood leukaemia of the acute lymphoblastic type – the most common childhood cancer in the world.

The study was conducted amongst children with Down's syndrome – who are 20-50 times more prone to childhood leukaemias than other children – and involved analysing the DNA sequence of patients at different stages of leukaemia.

The researchers uncovered that two key genes (called RAS and JAK) can mutate to turn normal blood cells into cancer cells. However, these two genes never mutate together, as one seems to exclude the other. This discovery means we can begin to identify which of the two genes are mutated in patients, and therefore more effectively target their cancer in lower doses (reducing toxicity for the patient) with less side-effects.

This discovery is a significant step forward in understanding the biological mechanisms causing leukaemia and will bring scientists closer to developing individually-tailored treatment.

Currently, one in six children in the general population does not respond well to standard therapy for leukaemia, and/or suffers from relapses and toxic side-effects of therapy. These figures of poor response and toxicity are even bigger among children with Down's syndrome.

The study was a collaboration between researchers at QMUL's Blizard Institute, the Lee Kong Chian School of Medicine, Nanyang Technological University Singapore and Schools of Medicine of the Universities of Geneva and Padua, and is published in leading journal Nature Communications.

Dean Nizetic, Professor of Cellular and Molecular Biology at Queen Mary University of London, and Professor of Molecular Medicine at Lee Kong Chian School of Medicine, Singapore, comments: "We believe our findings are a breakthrough in understanding the underlying causes of leukaemia and eventually we hope to design more tailored and effective treatment for this cancer, with less toxic drugs and less side-effects. This could benefit all children affected by the disease and potentially even cut the number of side effect-related deaths."

"Through our research we know people with Down's syndrome show signs of accelerated ageing and have higher accumulation of DNA damage compared to age-matched general population. However, paradoxically, they seem to be protected from most common cancers in adult age. Also, some people with Down's syndrome appear protected from other ageing-related diseases, such as dementia, atherosclerosis and diabetes. Therefore, studying cells from people with Down's syndrome could provide important clues in understanding the mechanisms of ageing, Alzheimer's, cancer, atherosclerosis, diabetes, and a number of other common conditions. Further research is needed in this important area."

INFORMATION:

About Queen Mary University of London

Queen Mary University of London is among the UK's leading research-intensive higher education institutions, with five campuses in the capital: Mile End, Whitechapel, Charterhouse Square, West Smithfield and Lincoln's Inn Fields.

A member of the Russell Group, Queen Mary is also one of the largest of the colleges of the University of London, with 17,800 students - 20 per cent of whom are from more than 150 countries.

Some 4,000 staff deliver world-class degrees and research across 21 departments, within three Faculties: Science and Engineering; Humanities and Social Sciences; and the School of Medicine and Dentistry.

Queen Mary has an annual turnover of £350m, research income worth £100m, and generates employment and output worth £700m to the UK economy each year.

Unique for London universities, Queen Mary has an integrated residential campus in Mile End - a 2,000-bed award-winning Student Village overlooking the scenic Regents Canal.

Scientists make major breakthrough in understanding leukemia

2014-08-14

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

Can our computers continue to get smaller and more powerful?

2014-08-13

From their origins in the 1940s as sequestered, room-sized machines designed for military and scientific use, computers have made a rapid march into the mainstream, radically transforming industry, commerce, entertainment and governance while shrinking to become ubiquitous handheld portals to the world.

This progress has been driven by the industry's ability to continually innovate techniques for packing increasing amounts of computational circuitry into smaller and denser microchips. But with miniature computer processors now containing millions of closely-packed transistor ...

UT Arlington team's work could lead to earlier diagnosis, treatment of mental diseases

2014-08-13

A computer science and engineering associate professor and her doctoral student graduate are using a genetic computer network inference model that eventually could predict whether a person will suffer from bipolar disorder, schizophrenia or another mental illness.

The findings are detailed in the paper "Inference of SNP-Gene Regulatory Networks by Integrating Gene Expressions and Genetic Perturbations," which was published in the June edition of Biomed Research International. The principal investigators were Jean Gao, an associate professor of computer science and engineering, ...

Three radars are better than one: Field campaign demonstrates two new instruments

2014-08-13

Putting three radars on a plane to measure rainfall may seem like overkill. But for the Integrated Precipitation and Hydrology Experiment field campaign in North Carolina recently, more definitely was better.

The three instruments, developed by the High Altitude Radar group at NASA's Goddard Space Flight Center in Greenbelt, Maryland, flew as part of the Global Precipitation Measurement (GPM) mission's six-week ground-validation program that took place May 1 through June 15 in the southern Appalachians, specifically to measure rain in difficult-to-forecast mountain regions. ...

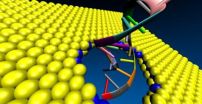

New material could enhance fast and accurate DNA sequencing

2014-08-13

CHAMPAIGN, Ill. — Gene-based personalized medicine has many possibilities for diagnosis and targeted therapy, but one big bottleneck: the expensive and time-consuming DNA-sequencing process.

Now, researchers at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign have found that nanopores in the material molybdenum disulfide (MoS2) could sequence DNA more accurately, quickly and inexpensively than anything yet available.

"One of the big areas in science is to sequence the human genome for under $1,000, the 'genome-at-home,'" said Narayana Aluru, a professor of mechanical ...

Patent examiners more likely to approve marginal inventions when pressed for time

2014-08-13

CHAMPAIGN, Ill. — Haste makes waste, as the old saying goes. And according to research from a University of Illinois expert in patent law, the same adage could be applied to the U.S. Patent and Trademark Office, where high-ranking examiners have a tendency to rubber-stamp patents of questionable merit due to time constraints.

The less time patent examiners are given to review an application, the more likely they are to grant patent protection to inventions "on the margin," says a study co-authored by Melissa Wasserman, the Richard and Anne Stockton Faculty Scholar and ...

Bones from nearly 50 ancient flying reptiles discovered

2014-08-13

Scientists discovered the bones of nearly 50 winged reptiles from a new species, Caiuajara dobruskii, that lived during the Cretaceous in southern Brazil, according to a study published August 13, 2014 in the open-access journal PLOS ONE by Paulo Manzig from Universidade do Contestado, Brazil, and colleagues.

The authors discovered the bones in a pterosaur bone bed in rocks from the Cretaceous period. They belonged to individuals ranging from young to adult, with wing spans ranging from 0.65-2.35m, allowing scientists to analyze how the bones fit into their clade, but ...

Embalming study 'rewrites' chapter in Egyptian history

2014-08-13

The origins of mummification may have started in ancient Egypt 1,500 years earlier than previously thought, according to a study published August 13, 2014 in the open-access journal PLOS ONE by Stephen Buckley from University of York and colleagues from Macquarie University and University of Oxford.

Previous evidence suggests that between ~4500 B.C. and 3100 B.C., Egyptian mummification consisted of bodies desiccating naturally through the action of the hot, dry desert sand. The early use of resins in artificial mummification has, until now, been limited to isolated occurrences ...

Little penguins forage together

2014-08-13

Most little penguins may search for food in groups, and even synchronize their movements during foraging trips, according to a study published August 13, 2014 in the open-access journal PLOS ONE by Maud Berlincourt and John Arnould from Deakin University in Australia.

Little penguins are the smallest penguin species and they live exclusively in southern Australia, New Zealand, and the Chatham Islands, but spend most of their lives at sea in search of food. Not much is known about group foraging behavior in seabirds due to the difficulty in observing their remote feeding ...

Young blue sharks use central North Atlantic nursery

2014-08-13

Blue sharks may use the central North Atlantic as a nursery prior to males and females moving through the ocean basin in distinctly different patterns, according to a study published August 13, 2014 in the open-access journal PLOS ONE by Frederic Vandeperre from University of the Azores, Portugal, and colleagues.

Shark populations typically organize by location and separate by sex and size, but these patterns remain poorly understood, particularly for exploited oceanic species such as the blue shark. The authors of this study employed a long-term electronic tagging experiment ...

Bacterial biosurgery shows promise for reducing the size of inoperable tumors

2014-08-13

Kansas City, MO. — Deep within most tumors lie areas that remain untouched by chemotherapy and radiation. These troublesome spots lack the blood and oxygen needed for traditional therapies to work, but provide the perfect target for a new cancer treatment using bacteria that thrive in oxygen-poor conditions. Now, researchers have shown that injections of a weakened version of one such anaerobic bacteria -- the microbe Clostridium novyi -- can shrink tumors in rats, pet dogs, and a human patient.

The findings from BioMed Valley Discoveries and a nationwide team of collaborators ...