8,000-year-old mutation key to human life at high altitudes

University of Utah-led study identifies genetic basis for Tibetan adaptation

2014-08-17

(Press-News.org) (SALT LAKE CITY) – In an environment where others struggle to survive, Tibetans thrive in the thin air on the Tibetan Plateau, with an average elevation of 14,800 feet. A study led by University of Utah scientists is the first to find a genetic cause for the adaptation – a single DNA base pair change that dates back 8,000 years – and demonstrate how it contributes to the Tibetans' ability to live in low oxygen conditions. The study appears online in the journal Nature Genetics on Aug. 17, 2014.

"These findings help us understand the unique aspects of Tibetan adaptation to high altitudes, and to better understand human evolution," said Josef Prchal, M.D., senior author and University of Utah professor of internal medicine.

The story behind the discovery is equally about cultural diplomacy as it is scientific advancement. Prchal traveled several times to Asia to meet with Chinese officials, and representatives of exiled Tibetans in India, to obtain permissions to recruit subjects for the study. But he quickly learned that without the trust of Tibetans, his efforts were futile. Wary of foreigners, they refused to donate blood for his research.

After returning to the U.S., Prchal couldn't believe his luck upon discovering that a native Tibetan, Tsewang Tashi, M.D., had just joined the Huntsman Cancer Institute at the University of Utah as a clinical fellow. When Prchal asked for his help, Tashi quickly agreed. "I realized the implications of his work not only for science as a whole but also for understanding what it means to be Tibetan," said Tashi. In another stroke of luck, Prchal received a long-awaited letter of support from the Dalai Lama. The two factors were instrumental in engaging the Tibetans' trust: more than 90, both from the U.S. and abroad, volunteered for the study.

First author Felipe Lorenzo, Ph.D., spent years combing through the Tibetans' DNA, and unlocking secrets from a "GC-rich" region that is notoriously difficult to penetrate. His hard work was worth it, for the Tibetans' DNA had a fascinating tale to tell. About 8,000 years ago, the gene EGLN1 changed by a single DNA base pair. Today, a relatively short time later on the scale of human history, 88% of Tibetans have the genetic variation, and it is virtually absent from closely related lowland Asians. The findings indicate the genetic variation endows its carriers with an advantage.

Prchal, collaborated with experts throughout the world, to determine what that advantage is. In those without the adaptation, low oxygen causes their blood to become thick with oxygen-carrying red blood cells - an attempt to feed starved tissues - which can cause long-term complications such as heart failure. The researchers found that the newly identified genetic variation protects Tibetans by decreasing the over-response to low oxygen.

These discoveries are but one chapter in a much larger story. The genetic adaptation likely causes other changes to the body that have yet to be understood. Plus, it is one of many as of yet unidentified genetic changes that collectively support life at high altitudes.

Prchal says the implications of the research extend beyond human evolution. Because oxygen plays a central role in human physiology and disease, a deep understanding of how high altitude adaptations work may lead to novel treatments for various diseases, including cancer. "There is much more that needs to be done, and this is just the beginning," he said.

At the beginning of the project, while in Asia, Prchal was amazed at how Tashi was able to establish a common ground with Tibetans. He helped them realize they had something unique to contribute. "When I tell my fellow Tibetans, 'Unlike other people, Tibetans can adapt better to living at high altitude,' they usually respond by a little initial surprise quickly followed by agreement," Tashi explained.

"Its as if I made them realize something new, which only then became obvious."

INFORMATION:

Summary

A genetic variation (mutation) in EGLN1 helps Tibetans adapt to living at high altitudes

The variation is 8,000 years old, relatively recent in human history

It is found in the vast majority of Tibetans, 88 percent

It is rarely found in closely related lowland Asians

It short-circuits a potentially deadly chronic response to low oxygen in which the blood becomes dangerously thick with oxygen-carrying red blood cells

This is the first report identifying, and functionally characterizing, a genetic basis for high altitude adaptation

"A genetic mechanism for Tibetan high-altitude adaptation" will be published online on Aug. 17, 2014, in Nature Genetics

Authors: Felipe R. Lorenzo, Chad Huff, Mikko Myllymäki, Benjamin Olenchock, Sabina Swierczek, Tsewang Tashi, Victor Gordeuk ,Tana Wuran, Ge Ri-Li, Donald McClain, Tahsin M. Khan, Parvaiz A. Koul, Prasenjit Guchhait, Mohamed E. Salama, Jinchuan Xing, Gregg L. Semenza, Ella Liberzon, Andrew Wilson, Tatum S. Simonson, Lynn B. Jorde, William G. Kaelin Jr., Peppi Koivunen, and Josef T. Prchal END

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

Microchip reveals how tumor cells transition to invasion

2014-08-17

VIDEO:

Cancer cells advance across a microchip designed to be an obstacle course for cells. The device sheds new light on how cancer cells invade and could be used to test...

Click here for more information.

PROVIDENCE, R.I. [Brown University] — Using a microengineered device that acts as an obstacle course for cells, researchers have shed new light on a cellular metamorphosis thought to play a role in tumor cell invasion throughout the body.

The epithelial-mesenchymal transition ...

'Cavity protection effect' helps to conserve quantum information

2014-08-17

The electronics we use for our computers only knows two different states: zero or one. Quantum systems on the other hand can be in different states at once, they can store a superposition of "zero" and "one". This phenomenon could be used to build ultrafast quantum computers, but there are several technological obstacles that have to be overcome first. The biggest problem is that quantum states are quickly destroyed due to interactions with the environment. At TU Wien (Vienna), scientists have now succeeded in using a protection effect to enhance the stability of a particularly ...

FDA-approved drug restores hair in patients with Alopecia Areata

2014-08-17

NEW YORK, NY (August 17, 2014) —Researchers at Columbia University Medical Center (CUMC) have identified the immune cells responsible for destroying hair follicles in people with alopecia areata, a common autoimmune disease that causes hair loss, and have tested an FDA-approved drug that eliminated these immune cells and restored hair growth in a small number of patients.

The results appear in today's online issue of Nature Medicine.

In the paper, the researchers report initial results from an ongoing clinical trial of the drug, which has produced complete hair regrowth ...

Fascinating rhythm: Light pulses illuminate a rare black hole

2014-08-17

The universe has so many black holes that it's impossible to count them all. There may be 100 million of these intriguing astral objects in our galaxy alone. Nearly all black holes fall into one of two classes: big, and colossal. Astronomers know that black holes ranging from about 10 times to 100 times the mass of our sun are the remnants of dying stars, and that supermassive black holes, more than a million times the mass of the sun, inhabit the centers of most galaxies.

But scattered across the universe like oases in a desert are a few apparent black holes of a more ...

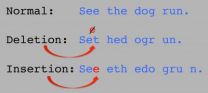

A shift in the code: New method reveals hidden genetic landscape

2014-08-17

Cold Spring Harbor, NY – With three billion letters in the human genome, it seems hard to believe that adding a DNA base here or removing a DNA base there could have much of an effect on our health. In fact, such insertions and deletions can dramatically alter biological function, leading to diseases from autism to cancer. Still, it is has been difficult to detect these mutations. Now, a team of scientists at Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory (CSHL) has devised a new way to analyze genome sequences that pinpoints so-called insertion and deletion mutations (known as "indels") ...

New home for an 'evolutionary misfit'

2014-08-17

One of the most bizarre-looking fossils ever found - a worm-like creature with legs, spikes and a head difficult to distinguish from its tail – has found its place in the evolutionary Tree of Life, definitively linking it with a group of modern animals for the first time.

The animal, known as Hallucigenia due to its otherworldly appearance, had been considered an 'evolutionary misfit' as it was not clear how it related to modern animal groups. Researchers from the University of Cambridge have discovered an important link with modern velvet worms, also known as onychophorans, ...

Stem cells reveal how illness-linked genetic variation affects neurons

2014-08-17

VIDEO:

Human neurons firing

Click here for more information.

A genetic variation linked to schizophrenia, bipolar disorder and severe depression wreaks havoc on connections among neurons in the developing brain, a team of researchers reports. The study, led by Guo-li Ming, M.D., Ph.D., and Hongjun Song, Ph.D., of the Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine and described online Aug. 17 in the journal Nature, used stem cells generated from people with and without mental illness ...

New Stanford research sheds light on how children's brains memorize facts

2014-08-17

As children learn basic arithmetic, they gradually switch from solving problems by counting on their fingers to pulling facts from memory. The shift comes more easily for some kids than for others, but no one knows why.

Now, new brain-imaging research gives the first evidence drawn from a longitudinal study to explain how the brain reorganizes itself as children learn math facts. A precisely orchestrated group of brain changes, many involving the memory center known as the hippocampus, are essential to the transformation, according to a study from the Stanford University ...

Suspect gene corrupts neural connections

2014-08-17

Researchers have long suspected that major mental disorders are genetically-rooted diseases of synapses – the connections between neurons. Now, investigators supported in part by the National Institutes of Health have demonstrated in patients' cells how a rare mutation in a suspect gene disrupts the turning on and off of dozens of other genes underlying these connections.

"Our results illustrate how genetic risk, abnormal brain development and synapse dysfunction can corrupt brain circuitry at the cellular level in complex psychiatric disorders," explained Hongjun Song, ...

Stuck in neutral: Brain defect traps schizophrenics in twilight zone

2014-08-17

People with schizophrenia struggle to turn goals into actions because brain structures governing desire and emotion are less active and fail to pass goal-directed messages to cortical regions affecting human decision-making, new research reveals.

Published in Biological Psychiatry, the finding by a University of Sydney research team is the first to illustrate the inability to initiate goal-directed behaviour common in people with schizophrenia.

The finding may explain why people with schizophrenia have difficulty achieving real-world goals such as making friends, completing ...

LAST 30 PRESS RELEASES:

Scientists discover why we know when to stop scratching an itch

A hidden reason inner ear cells die – and what it means for preventing hearing loss

Researchers discover how tuberculosis bacteria use a “stealth” mechanism to evade the immune system

New microscopy technique lets scientists see cells in unprecedented detail and color

Sometimes less is more: Scientists rethink how to pack medicine into tiny delivery capsules

Scientists build low-cost microscope to study living cells in zero gravity

The Biophysical Journal names Denis V. Titov the 2025 Paper of the Year-Early Career Investigator awardee

Scientists show how your body senses cold—and why menthol feels cool

Scientists deliver new molecule for getting DNA into cells

Study reveals insights about brain regions linked to OCD, informing potential treatments

Does ocean saltiness influence El Niño?

2026 Young Investigators: ONR celebrates new talent tackling warfighter challenges

Genetics help explain who gets the ‘telltale tingle’ from music, art and literature

Many Americans misunderstand medical aid in dying laws

Researchers publish landmark infectious disease study in ‘Science’

New NSF award supports innovative role-playing game approach to strengthening research security in academia

Kumar named to ACMA Emerging Leaders Program for 2026

AI language models could transform aquatic environmental risk assessment

New isotope tools reveal hidden pathways reshaping the global nitrogen cycle

Study reveals how antibiotic structure controls removal from water using biochar

Why chronic pain lasts longer in women: Immune cells offer clues

Toxic exposure creates epigenetic disease risk over 20 generations

More time spent on social media linked to steroid use intentions among boys and men

New study suggests a “kick it while it’s down” approach to cancer treatment could improve cure rates

Milken Institute, Ann Theodore Foundation launch new grant to support clinical trial for potential sarcoidosis treatment

New strategies boost effectiveness of CAR-NK therapy against cancer

Study: Adolescent cannabis use linked to doubling risk of psychotic and bipolar disorders

Invisible harms: drug-related deaths spike after hurricanes and tropical storms

Adolescent cannabis use and risk of psychotic, bipolar, depressive, and anxiety disorders

Anxiety, depression, and care barriers in adults with intellectual and developmental disabilities

[Press-News.org] 8,000-year-old mutation key to human life at high altitudesUniversity of Utah-led study identifies genetic basis for Tibetan adaptation