(Press-News.org) HOUSTON – (Aug. 18, 2014) – Rice University scientists have won a race to find the crystal structure of the first virus known to infect the most abundant animal on Earth.

The Rice labs of structural biologist Yizhi Jane Tao and geneticist Weiwei Zhong, with help from researchers at Baylor College of Medicine and Washington University, analyzed the Orsay virus that naturally infects a certain type of nematode, the worms that make up 80 percent of the living animal population.

The research reported today in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences will help scientists study how viruses interact with their nematode hosts. It may also allow them to customize the virus to attack parasitic or pathogenic worms. The research may also lead to new information about how viruses attack other species, including humans, which have thousands of genes that are identical to those found in nematodes.

Tao's lab specializes in X-ray crystallography, through which scientists determine the atom-by-atom structures of viruses, proteins and other macromolecules. Once a virus' structure is identified, biologists can look for binding sites that allow the virus to attach to its target. Scientists can then search for ways to modify the sites through genetic engineering or design drugs to block viruses.

Zhong, who studies gene networks in Caenorhabditis elegans to trace signal pathways common to all animals, said she'd been looking for this opportunity for some time. "We had talked before 2011 about the fact that there were no known viruses that affect nematodes," Tao confirmed. "Then in 2011, there it was."

Zhong then asked Marie-Anne Félix and co-author David Wang, who discovered the infected worm in an apple orchard in France, for a sample of the virus. At that time, the Rice researchers learned others were also working to find the structure.

Tao's lab began by synthesizing the Orsay capsid protein and then coaxed the proteins to self-assemble into structures that were identical to the full virus. A comparison of these structures with electron microscope images of the actual virus confirmed their success.

"We got the crystals in May after three months of molecular cloning, expression and purification of the proteins," said lead author Yusong Guo, a graduate student co-mentored by Tao and Zhong. "Then we spent about a year-and-a-half to actually solve the structure as fast and accurately as possible, knowing that other groups were competing with us."

Their efforts led to a detailed structural model of the viral capsid, the hard, spiky shell that protects the infectious contents as the virus searches for and then attaches to a host cell.

Guo's structure showed the Orsay capsid consists of 180 copies of the capsid protein, each contributing to one of 60 spikes that adorn the shell. Tao said the capsid structure revealed surprising similarity to a group of fish-infecting viruses called nodaviruses. The researchers also observed similarities in the part of the protein that forms the spikes to the hepatitis E virus and calicivirus, suggesting possible evolutionary relationships between them.

They also found they could destabilize the virus by modifying one end -- the N-terminal arm -- of the capsid protein.

Zhong said the virus doesn't kill its host, but causes intestinal distress. "That's actually a sign that these two species (the worm and the virus) have been coevolving for a long time, because if a virus kills its host, they're not going to coexist for long," she said. "The worm and the virus thus make a good model system to study host-virus interactions."

The capsid spike structure is important, Tao said, because "it likely interacts with the host cell receptors. Now that we know this domain, we can specifically change it so that maybe, instead of targeting this worm, it will target a different species of worm."

Two other viruses have since been found to infect a different strain of nematode, but there's satisfaction in being the first to detail the first such virus discovered.

"There are 20,000 genes in C. elegans, and 8,000 of them are conserved between humans and worms," Zhong said. "How many of those genes are involved in antiviral defense? We can study that now."

INFORMATION:

The paper's co-authors are graduate student Corey Hryc, Assistant Director Joanita Jakana and Director Wah Chiu of the National Center for Macromolecular Imaging at Baylor College of Medicine, and Hongbing Jiang, a postdoctoral researcher, and Wang, an associate professor of molecular microbiology and pathology and immunology at Washington University. Zhong is an assistant professor of biochemistry and cell biology. Tao is an associate professor of biochemistry and cell biology.

The Welch Foundation, the National Institutes of Health, the Kresge Science Initiative Endowment Fund at Rice, the Burroughs Wellcome Fund and the Gulf Coast Consortia supported the research.

David Ruth

713-348-6327

david@rice.edu

Mike Williams

713-348-6728

mikewilliams@rice.edu

Read the abstract at http://www.pnas.org/cgi/doi/10.1073/pnas.1407122111

This news release can be found online at news.rice.edu.

Follow Rice News and Media Relations via Twitter @RiceUNews

Related Materials:

Tao Laboratory: http://ytao.rice.edu/members.html

Zhong Lab: http://wormlab.rice.edu

Rice's Wiess School of Natural Sciences: http://naturalsciences.rice.edu

Images for download:

http://news.rice.edu/wp-content/uploads/2014/08/0825_WORMS-1-WEB.jpg

A nematode from the Rice lab of biochemist Weiwei Zhong. Nematodes are favorite models of biological systems for their relative simplicity, their transparency and the ease with which scientists can manipulate their genetic sequences. (Credit: Zhong Lab/Rice University)

http://news.rice.edu/wp-content/uploads/2014/08/0825_WORMS-2-WEB.jpg

Rice University researchers have determined the crystal structure of the Orsay virus known to infect at least one type of nematode. The structure of the viral shell known as a capsid, seen in a computer model, will help scientists understand how such viruses infect their targets. (Credit: Tao Laboratory/Rice University)

http://news.rice.edu/wp-content/uploads/2014/08/0825_WORMS-3-WEB.jpg

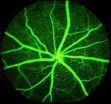

This cryo-electron microscopy image of the Orsay virus is a match for a model of the fine structure of the virus shell determined by researchers at Rice University. Rice scientists analyzed X-ray crystallography images of the shell to detail how its atoms are arranged. (Credit: Tao Laboratory/Rice University)

http://news.rice.edu/wp-content/uploads/2014/08/0825_WORMS-4-web.jpg

Rice University researchers, from left, Professors Weiwei Zhong and Yizhi Jane Tao and graduate student Yusong Guo, have won a race to determine the structure of the first virus known to naturally infect nematodes. The work is valuable to those who study virus-host interactions. (Credit: Jeff Fitlow/Rice University)

Located on a 300-acre forested campus in Houston, Rice University is consistently ranked among the nation's top 20 universities by U.S. News & World Report. Rice has highly respected schools of Architecture, Business, Continuing Studies, Engineering, Humanities, Music, Natural Sciences and Social Sciences and is home to the Baker Institute for Public Policy. With 3,920 undergraduates and 2,567 graduate students, Rice's undergraduate student-to-faculty ratio is just over 6-to-1. Its residential college system builds close-knit communities and lifelong friendships, just one reason why Rice is highly ranked for best quality of life by the Princeton Review and for best value among private universities by Kiplinger's Personal Finance. To read "What they're saying about Rice," go here.

Worm virus details come to light

Rice University scientists win race to find structure of rare nematode virus

2014-08-18

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

Innate lymphoid cells elicit T cell responses

2014-08-18

In case of an inflammation the body releases substances that increase the immune defense. During chronic inflammation, this immune response gets out of control and can induce organ damage. A research group from the Department of Biomedicine at the University and the University Children's Hospital of Basel now discovered that innate lymphoid cells become activated and induce specific T and B cell responses during inflammation. These lymphoid cells are thus an important target for the treatment of infection and chronic inflammation. The study was recently published in the ...

Aspirin, take 2

2014-08-18

Hugely popular non-steroidal anti-inflammation drugs like aspirin, naproxen (marketed as Aleve) and ibuprofen (Advil, Motrin) all work by inhibiting or killing an enzyme called cyclooxygenase – a key catalyst in production of hormone-like lipid compounds called prostaglandins that are linked to a variety of ailments, from headaches and arthritis to menstrual cramps and wound sepsis.

In a new paper, published this week in the online early edition of PNAS, researchers at the University of California, San Diego School of Medicine conclude that aspirin has a second effect: ...

Pygmy phenotype developed many times, adaptive to rainforest

2014-08-18

The small body size associated with the pygmy phenotype is probably a selective adaptation for rainforest hunter-gatherers, according to an international team of researchers, but all African pygmy phenotypes do not have the same genetic underpinning, suggesting a more recent adaptation than previously thought.

"I'm interested in how rainforest hunter-gatherers have adapted to their very challenging environments," said George H. Perry, assistant professor of anthropology and biology, Penn State. "Tropical rainforests are difficult for humans to live in. It is extremely ...

Bionic liquids from lignin

2014-08-18

While the powerful solvents known as ionic liquids show great promise for liberating fermentable sugars from lignocellulose and improving the economics of advanced biofuels, an even more promising candidate is on the horizon – bionic liquids.

Researchers at the U.S. Department of Energy's Joint BioEnergy Institute (JBEI) have developed "bionic liquids" from lignin and hemicellulose, two by-products of biofuel production from biorefineries. JBEI is a multi-institutional partnership led by Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory (Berkeley Lab) that was established by the ...

Proteins critical to wound healing identified

2014-08-18

Mice missing two important proteins of the vascular system develop normally and appear healthy in adulthood, as long as they don't become injured. If they do, their wounds don't heal properly, a new study shows.

The research, at Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis, may have implications for treating diseases involving abnormal blood vessel growth, such as the impaired wound healing often seen in diabetes and the loss of vision caused by macular degeneration.

The study appears Aug. 18 in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (PNAS) online ...

Climate change will threaten fish by drying out Southwest US streams, study predicts

2014-08-18

COLUMBUS, Ohio – Fish species native to a major Arizona watershed may lose access to important segments of their habitat by 2050 as surface water flow is reduced by the effects of climate warming, new research suggests.

Most of these fish species, found in the Verde River Basin, are already threatened or endangered. Their survival relies on easy access to various resources throughout the river and its tributary streams. The species include the speckled dace (Rhinichthys osculus), roundtail chub (Gila robusta) and Sonora sucker (Catostomus insignis).

A key component ...

Trees and shrubs invading critical grasslands, diminish cattle production

2014-08-18

TEMPE, Ariz. – Half of the Earth's land mass is made up of rangelands, which include grasslands and savannas, yet they are being transformed at an alarming rate. Woody plants, such as trees and shrubs, are moving in and taking over, leading to a loss of critical habitat and causing a drastic change in the ability of ecosystems to produce food — specifically meat.

Researchers with Arizona State University's School of Life Sciences led an investigation that quantified this loss in both the United States and Argentina. The study's results are published in today's online ...

Researchers obtain key insights into how the internal body clock is tuned

2014-08-18

DALLAS – August 18, 2014 – Researchers at UT Southwestern Medical Center have found a new way that internal body clocks are regulated by a type of molecule known as long non-coding RNA.

The internal body clocks, called circadian clocks, regulate the daily "rhythms" of many bodily functions, from waking and sleeping to body temperature and hunger. They are largely "tuned" to a 24-hour cycle that is influenced by external cues such as light and temperature.

"Although we know that long non-coding RNAs are abundant in many organisms, what they do in the body, and how they ...

UM research improves temperature modeling across mountainous landscapes

2014-08-18

MISSOULA – New research by University of Montana doctoral student Jared Oyler provides improved computer models for estimating temperature across mountainous landscapes.

The work was published Aug. 12 in the International Journal of Climatology in an article titled "Creating a topoclimatic daily air temperature dataset for the conterminous United States using homogenized station data and remotely sensed land skin temperature."

Collaborating with UM faculty co-authors Ashley Ballantyne, Kelsey Jencso, Michael Sweet and Steve Running, Oyler provided a new climate dataset ...

Passport study reveals vulnerability in photo-ID security checks

2014-08-18

Security systems based on photo identification could be significantly improved by selecting staff who have an aptitude for this very difficult visual task, a study of Australian passport officers suggests.

Previous research has shown that people find it challenging to match unfamiliar faces.

"Despite this, photo-ID is still widely used in security settings. Whenever we cross a border, apply for a passport or access secure premises, our appearance is checked against a photograph," says UNSW psychologist Dr David White.

To find out whether people who regularly carry out ...

LAST 30 PRESS RELEASES:

Microalgae-derived biochar enables fast, low-cost detection of hydrogen peroxide

Researchers highlight promise of biochar composites for sustainable 3D printing

Machine learning helps design low-cost biochar to fight phosphorus pollution in lakes

Urine tests confirm alcohol consumption in wild African chimpanzees

Barshop Institute to receive up to $38 million from ARPA-H, anchoring UT San Antonio as a national leader in aging and healthy longevity science

Anion-cation synergistic additives solve the "performance triangle" problem in zinc-iodine batteries

Ancient diets reveal surprising survival strategies in prehistoric Poland

Pre-pregnancy parental overweight/obesity linked to next generation’s heightened fatty liver disease risk

Obstructive sleep apnoea may cost UK + US economies billions in lost productivity

Guidelines set new playbook for pediatric clinical trial reporting

Adolescent cannabis use may follow the same pattern as alcohol use

Lifespan-extending treatments increase variation in age at time of death

From ancient myths to ‘Indo-manga’: Artists in the Global South are reframing the comic

Putting some ‘muscle’ into material design

House fires release harmful compounds into the air

Novel structural insights into Phytophthora effectors challenge long-held assumptions in plant pathology

Q&A: Researchers discuss potential solutions for the feedback loop affecting scientific publishing

A new ecological model highlights how fluctuating environments push microbes to work together

Chapman University researcher warns of structural risks at Grand Renaissance Dam putting property and lives in danger

Courtship is complicated, even in fruit flies

Columbia announces ARPA-H contract to advance science of healthy aging

New NYUAD study reveals hidden stress facing coral reef fish in the Arabian Gulf

36 months later: Distance learning in the wake of COVID-19

Blaming beavers for flood damage is bad policy and bad science, Concordia research shows

The new ‘forever’ contaminant? SFU study raises alarm on marine fiberglass pollution

Shorter early-life telomere length as a predictor of survival

Why do female caribou have antlers?

How studying yeast in the gut could lead to new, better drugs

Chemists thought phosphorus had shown all its cards. It surprised them with a new move

A feedback loop of rising submissions and overburdened peer reviewers threatens the peer review system of the scientific literature

[Press-News.org] Worm virus details come to lightRice University scientists win race to find structure of rare nematode virus