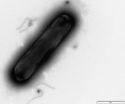

(Press-News.org) A fast-sensitive "electronic-nose" for sniffing the highly infectious bacteria C. diff, that causes diarrhoea, temperature and stomach cramps, has been developed by a team at the University of Leicester.

Using a mass spectrometer, the research team has demonstrated that it is possible to identify the unique 'smell' of C. diff which would lead to rapid diagnosis of the condition.

What is more, the Leicester team say it could be possible to identify different strains of the disease simply from their smell – a chemical fingerprint - helping medics to target the particular condition.

The research is published on-line in the journal Metabolomics.

Professor Paul Monks, from the Department of Chemistry, said: "The rapid detection and identification of the bug Clostridium difficile (often known as C. diff) is a primary concern in healthcare facilities. Rapid and accurate diagnoses are important to reduce Clostridum difficile infections, as well as to provide the right treatment to infected patients.

"Delayed treatment and inappropriate antibiotics not only cause high morbidity and mortality, but also add costs to the healthcare system through lost bed days.

Different strains of C. difficile can cause different symptoms and may need to be treated differently so a test that could determine not only an infection, but what type of infection could lead to new treatment options."

The new published research from the University of Leicester has shown that is possible to 'sniff' the infection for rapid detection of Clostridium difficile. The team have measured the Volatile Organic Compounds (VOCs) given out by different of strains of Clostridium difficile and have shown that many of them have a unique "smell". In particular, different strains show different chemical fingerprints which are detected by a mass spectrometer.

The work was a collaboration between University chemists who developed the "electronic-nose" for sniffing volatiles and a colleague in microbiology who has a large collection of well characterised strains of Clostridium difficile.

The work suggests that the detection of the chemical fingerprint may allow for a rapid means of identifying C. difficile infection, as well as providing markers for the way the different strains grow.

Professor Monks added: "Our approach may lead to a rapid clinical diagnostic test based on the VOCs released from faecal samples of patients infected with C. difficile. We do not underestimate the challenges in sampling and attributing C. difficile VOCs from faecal samples."

Dr Martha Clokie, from the Department of Microbiology and Immunology, added: "Current tests for C. difficile don't generally give strain information - this test could allow doctors to see what strain was causing the illness and allow doctors to tailor their treatment."

Professor Andy Ellis, from the Department of Chemistry, said: "This work shows great promise. The different strains of C. diff have significantly different chemical fingerprints and with further research we would hope to be able to develop a reliable and almost instantaneous tool for detecting a specific strain, even if present in very small quantities."

INFORMATION:

More info on C. diff: http://www.nhs.uk/conditions/clostridium-difficile/pages/introduction.aspx

Scientists develop 'electronic nose' for rapid detection of C. diff infection

Research from University of Leicester sniffs out smell of disease in feces

2014-09-01

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

Why plants in the office make us more productive

2014-09-01

'Green' offices with plants make staff happier and more productive than 'lean' designs stripped of greenery, new research shows.

In the first field study of its kind, published today, researchers found enriching a 'lean' office with plants could increase productivity by 15%.

The team examined the impact of 'lean' and 'green' offices on staff's perceptions of air quality, concentration, and workplace satisfaction, and monitored productivity levels over subsequent months in two large commercial offices in the UK and The Netherlands.

Lead researcher Marlon Nieuwenhuis, ...

Doctor revalidation needs to address 7 key issues for success, claims report

2014-09-01

New research launched today, 1st September 2014, has concluded that there are seven key issues that need to be addressed to ensure the future success of doctor revalidation, the most profound revision in medical regulation since the Medical Act of 1858.

The research has been funded by the Health Foundation, an independent health care charity, as part of a long-term programme looking at different aspects of revalidation. The work has been carried out by academics at the Collaboration for the Advancement of Medical Education, Research and Assessment (CAMERA) at Plymouth ...

Memory in silent neurons

2014-08-31

When we learn, we associate a sensory experience either with other stimuli or with a certain type of behaviour. The neurons in the cerebral cortex that transmit the information modify the synaptic connections that they have with the other neurons. According to a generally-accepted model of synaptic plasticity, a neuron that communicates with others of the same kind emits an electrical impulse as well as activating its synapses transiently. This electrical pulse, combined with the signal received from other neurons, acts to stimulate the synapses. How is it that some neurons ...

A new synthetic amino acid for an emerging class of drugs

2014-08-31

One of the greatest challenges in modern medicine is developing drugs that are highly effective against a target, but with minimal toxicity and side-effects to the patient. Such properties are directly related to the 3D structure of the drug molecule. Ideally, the drug should have a shape that is perfectly complementary to a disease-causing target, so that it binds it with high specificity. Publishing in Nature Chemistry, EPFL scientists have developed a synthetic amino acid that can impact the 3D structure of bioactive peptides and enhance their potency.

Peptides and ...

Discovery reveals how bacteria distinguish harmful vs. helpful viruses

2014-08-31

When they are not busy attacking us, germs go after each other. But when viruses invade bacteria, it doesn't always spell disaster for the infected microbes: Sometimes viruses actually carry helpful genes that a bacterium can harness to, say, expand its diet or better attack its own hosts.

Scientists have assumed the bacterial version of an immune system would robotically destroy anything it recognized as invading viral genes. However, new experiments at Rockefeller University have now revealed that one variety of the bacterial immune system known as the CRISPR-Cas system ...

Why sibling stars look alike: Early, fast mixing in star-birth clouds

2014-08-31

VIDEO:

This 11-second movie shows a computational simulation of a collision of two converging streams of interstellar gas, leading to collapse and formation of a star cluster at the center. Face-on...

Click here for more information.

Stars are made mostly of hydrogen and helium, but they also contain trace amounts of other elements, such as carbon, oxygen, iron, and even more exotic substances. By carefully measuring the wavelengths (colors) of light coming from a star, astronomers ...

Mixing in star-forming clouds explains why sibling stars look alike

2014-08-31

VIDEO:

This computer simulation shows the collision of two streams of interstellar gas, leading to gravitational collapse of the gas and the formation of a star cluster at the center. The...

Click here for more information.

The chemical uniformity of stars in the same cluster is the result of turbulent mixing in the clouds of gas where star formation occurs, according to a study by astrophysicists at the University of California, Santa Cruz. Their results, published August 31 in ...

Antarctic sea-level rising faster than global rate

2014-08-31

A new study of satellite data from the last 19 years reveals that fresh water from melting glaciers has caused the sea-level around the coast of Antarctica to rise by 2cm more than the global average of 6cm.

Researchers at the University of Southampton detected the rapid rise in sea-level by studying satellite scans of a region that spans more than a million square kilometres.

The melting of the Antarctic ice sheet and the thinning of floating ice shelves has contributed an excess of around 350 gigatonnes of freshwater to the surrounding ocean. This has led to a reduction ...

Changing global diets is vital to reducing climate change

2014-08-31

A new study, published today in Nature Climate Change, suggests that – if current trends continue – food production alone will reach, if not exceed, the global targets for total greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions in 2050.

The study's authors say we should all think carefully about the food we choose and its environmental impact. A shift to healthier diets across the world is just one of a number of actions that need to be taken to avoid dangerous climate change and ensure there is enough food for all.

As populations rise and global tastes shift towards meat-heavy Western ...

A new way to diagnose malaria

2014-08-31

CAMBRIDGE, MA -- Over the past several decades, malaria diagnosis has changed very little. After taking a blood sample from a patient, a technician smears the blood across a glass slide, stains it with a special dye, and looks under a microscope for the Plasmodium parasite, which causes the disease. This approach gives an accurate count of how many parasites are in the blood — an important measure of disease severity — but is not ideal because there is potential for human error.

A research team from the Singapore-MIT Alliance for Research and Technology (SMART) has now ...

LAST 30 PRESS RELEASES:

Researchers determine structural motifs of water undecamer cluster

Researchers enhance photocatalytic hydrogen evolution performance of covalent organic frameworks by constitutional isomer strategy

Molecular target drives immunogenicity in cancer immunotherapy

Plant cell structure could hold key to cancer therapies and improved crops

Sustainable hydrogen peroxide production: Breakthroughs in electrocatalyst design for on-site synthesis

Cash rewards for behavior change: A review of financial incentives science in one health contexts and implications

One Health antimicrobial resistance modelling: from science to policy

Artificial feeding platform transforms study of ticks and their diseases

Researchers uncover microscopic mechanism of alkali species dissolution in water clusters

Methionine restriction for cancer therapy: A comprehensive review of mechanisms and clinical applications

White House autism briefing linked to swift shifts in prescribing patterns, study finds

Specialist palliative care can save the NHS up to £8,000 per person and improves quality of life

New research warns charities against ‘AI shortcut’ to empathy

Cannabis compounds show promise in fighting fatty liver disease

Study in mice reveals the brain circuits behind why we help others

Online forum to explore how organic carbon amendments can improve soil health while storing carbon

Turning agricultural plastic waste into valuable chemicals with biochar catalysts

Hidden viral networks in soil microplastics may shape the future of sustainable agriculture

Americans don’t just fear driverless cars will crash — they fear mass job losses

Mayo Clinic researchers find combination therapy reduces effects of ‘zombie cells’ in diabetic kidney disease

Preventing breast cancer resistance to CDK4/6 inhibitors using genomic findings

Carbon nanotube fiber ‘textile’ heaters could help industry electrify high-temperature gas heating

Improving your biological age gap is associated with better brain health

Learning makes brain cells work together, not apart

Engineers improve infrared devices using century-old materials

Physicists mathematically create the first ‘ideal glass’

Microbe exposure may not protect against developing allergic disease

Forest damage in Europe to rise by around 20% by 2100 even if warming is limited to 2°C

Rapid population growth helped koala’s recovery from severe genetic bottleneck

CAR-expressing astrocytes target and clear amyloid-β in mouse model of Alzheimer’s disease

[Press-News.org] Scientists develop 'electronic nose' for rapid detection of C. diff infectionResearch from University of Leicester sniffs out smell of disease in feces