(Press-News.org) LA JOLLA—In most of the tissues of the body, specialized immune cells are entrusted with the task of engulfing the billions of dead cells that are generated every day. When these garbage disposals don't do their job, dead cells and their waste products rapidly pile up, destroying healthy tissue and leading to autoimmune diseases such as lupus and rheumatoid arthritis.

Now, Salk scientists have discovered how two critical receptors on these garbage-eating cells identify and engulf dead cells in very different environments, as detailed today in Nature Immunology.

"To target these receptors as treatments for autoimmune disease and cancer, it's important to know exactly which receptor is doing what. And this discovery tells us that," says senior author of the work Greg Lemke, Salk professor of molecular neurobiology and the holder of Salk's Françoise Gilot-Salk Chair.

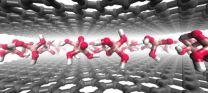

The garbage-disposing cells, known as macrophages, have arrays of receptors on their surface, two of which—called Mer and Axl—are responsible for recognizing dead cells in normal environments and inflamed environments, respectively. Mer operates as a "steady-as-she-goes" receptor, clearing out dead cells in healthy tissues on a daily basis. Axl, in contrast, acts as an "all-hands-on-deck" receptor, kicking macrophages into action in inflammatory settings that result from infection or tissue trauma. These inflamed environments have many more dead cells.

"We thought Axl and Mer were doing the same job, and they are: they both recognize a so-called 'eat me' signal displayed on the surface of dead cells. But it turns out that they work in very different settings," says Lemke, whose lab first discovered the two receptors—which, along with a third, make up the TAM family—two decades ago. Lemke and colleagues explored the roles of TAM receptors in the brain initially, but observed that the absence of these receptors had dramatic effects on the immune system, including the development of autoimmune disease. The receptors have since become a growing focus for cancer and autoimmune research, and previous work has found that these three receptors are important in other areas, including the intestines, reproductive organs and vision.

"This basic research focus allowed us to discover a completely new aspect of immune regulation that no one—including any immunologist—had known about before," adds Lemke.

In the new work, the researchers found multiple critical differences between Axl and Mer. For example, the receptors use different molecules—called ligands—to be activated: Axl has a single such ligand and, once engaged, is quickly cleaved off of the surface of the macrophage. Levels of the free-floating Axl in the blood have turned out to be an accurate, general biomarker for inflammation, quickly showing up in the circulation after tissue trauma or injury.

"We compared the behavior and regulation of the receptors, and the results were very striking," says first author Anna Zagórska. "In response to many different pro-inflammatory stimuli, Axl was upregulated and Mer was not. In contrast, immunosuppressive corticosteroids, which are widely used to suppress inflammation in people, upregulated Mer and suppressed Axl. These differences were our entry point to the study."

Next, the researchers are looking into each receptor's activity in more detail. The team is finding that these receptors are unusual in that they have a three-step binding procedure, whereas most cell receptors bind in one step. Exploring and understanding this process will help to lead to more targeted therapeutics for cancers and other diseases in which the receptors are thought to act.

INFORMATION:

Authors on the paper include Anna Zagórska, Paqui Través, Erin Lew, Ian Dransfield and Greg Lemke.

The work was funded by the National Institutes of Health, the Leona M. and Harry B. Helmsley Charitable Trust, the Nomis Foundation, the H.N. and Frances C. Berger Foundation, the Fritz B. Burns Foundation, the HKT Foundation, the Human Frontiers Science Program, and the Leukemia and Lymphoma Society.

About the Salk Institute for Biological Studies

The Salk Institute for Biological Studies is one of the world's preeminent basic research institutions, where internationally renowned faculty probes fundamental life science questions in a unique, collaborative, and creative environment. Focused both on discovery and on mentoring future generations of researchers, Salk scientists make groundbreaking contributions to our understanding of cancer, aging, Alzheimer's, diabetes and infectious diseases by studying neuroscience, genetics, cell and plant biology, and related disciplines.

Faculty achievements have been recognized with numerous honors, including Nobel Prizes and memberships in the National Academy of Sciences. Founded in 1960 by polio vaccine pioneer Jonas Salk, MD, the Institute is an independent nonprofit organization and architectural landmark.

Dynamic duo takes out the cellular trash

Salk scientists identify how immune cells use two critical receptors to clear dead cells from the body, pointing the way to new autoimmune and cancer therapies

2014-09-07

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

Platelet-like particles augment natural blood clotting for treating trauma

2014-09-07

A new class of synthetic platelet-like particles could augment natural blood clotting for the emergency treatment of traumatic injuries – and potentially offer doctors a new option for curbing surgical bleeding and addressing certain blood clotting disorders without the need for transfusions of natural platelets.

The clotting particles, which are based on soft and deformable hydrogel materials, are triggered by the same factor that initiates the body's own clotting processes. Testing done in animal models and in a simulated circulatory system suggest that the particles ...

Why age reduces our stem cells' ability to repair muscle

2014-09-07

Ottawa, Canada (September 7, 2014) — As we age, stem cells throughout our bodies gradually lose their capacity to repair damage, even from normal wear and tear. Researchers from the Ottawa Hospital Research Institute and University of Ottawa have discovered the reason why this decline occurs in our skeletal muscle. Their findings were published online today in the influential journal Nature Medicine.

A team led by Dr. Michael Rudnicki, senior scientist at the Ottawa Hospital Research Institute and professor of medicine at the University of Ottawa, found that as muscle ...

Rethinking the basic science of graphene synthesis

2014-09-07

A new route to making graphene has been discovered that could make the 21st century's wonder material easier to ramp up to industrial scale. Graphene -- a tightly bound single layer of carbon atoms with super strength and the ability to conduct heat and electricity better than any other known material -- has potential industrial uses that include flexible electronic displays, high-speed computing, stronger wind-turbine blades, and more-efficient solar cells, to name just a few under development.

In the decade since Nobel laureates Konstantin Novoselov and Andre Geim proved ...

Targeting the protein-making machinery to stop harmful bacteria

2014-09-07

One challenge in killing off harmful bacteria is that many of them develop a resistance to antibiotics. Researchers at the University of Rochester are targeting the formation of the protein-making machinery in those cells as a possible alternate way to stop the bacteria. And Professor of Biology Gloria Culver has, for the first time, isolated the middle-steps in the process that creates that machinery—called the ribosomes.

"No one had a clear understanding of what happened inside an intact bacterial cell," said Culver, "And without that understanding, it would not be ...

Continuing Bragg legacy of structure determination

2014-09-07

Over 100 years since the Nobel Prize-winning father and son team Sir William and Sir Lawrence Bragg pioneered the use of X-rays to determine crystal structure, University of Adelaide researchers have made significant new advances in the field.

Published in the journal Nature Chemistry today, Associate Professors Christian Doonan and Christopher Sumby and their team in the School of Chemistry and Physics, have developed a new material for examining structures using X-rays without first having to crystallise the substance.

"2014 is the International Year of Crystallography, ...

Ultraviolet light-induced mutation drives many skin cancers, Stanford researchers find

2014-09-07

A genetic mutation caused by ultraviolet light is likely the driving force behind millions of human skin cancers, according to researchers at the Stanford University School of Medicine.

The mutation occurs in a gene called KNSTRN, which is involved in helping cells divide their DNA equally during cell division.

Genes that cause cancer when mutated are known as oncogenes. Although KNSTRN hasn't been previously implicated as a cause of human cancers, the research suggests it may be one of the most commonly mutated oncogenes in the world.

"This previously unknown oncogene ...

Ultra-thin, high-speed detector captures unprecedented range of light waves

2014-09-07

New research at the University of Maryland could lead to a generation of light detectors that can see below the surface of bodies, walls, and other objects. Using the special properties of graphene, a two-dimensional form of carbon that is only one atom thick, a prototype detector is able to see an extraordinarily broad band of wavelengths. Included in this range is a band of light wavelengths that have exciting potential applications but are notoriously difficult to detect: terahertz waves, which are invisible to the human eye.

A research paper about the new detector ...

Researchers discover a key to making new muscles

2014-09-07

La Jolla, Calif., September 7, 2014 -- Researchers at Sanford-Burnham Medical Research Institute (Sanford-Burnham) have developed a novel technique to promote tissue repair in damaged muscles. The technique also creates a sustainable pool of muscle stem cells needed to support multiple rounds of muscle repair. The study, published September 7 in Nature Medicine, provides promise for a new therapeutic approach to treating the millions of people suffering from muscle diseases, including those with muscular dystrophies and muscle wasting associated with cancer and aging.

There ...

UK study identifies molecule that induces cancer-killing protein

2014-09-07

LEXINGTON, Ky. (Sept. 8, 2014) – A new study by University of Kentucky researchers has identified a novel molecule named Arylquin 1 as a potent inducer of Par-4 secretion from normal cells. Par-4 is a protein that acts as a tumor suppressor, killing cancer cells while leaving normal cells unharmed.

Normal cells secrete small amounts of Par-4 on their own, but this amount is not enough to kill cancer cells. Notably, if Par-4 secretion is suppressed, this leads to tumor growth.

Published in Nature Chemical Biology, the UK study utilized lab cultures and animal models ...

Each day in the hospital raises risk of multidrug-resistant infection

2014-09-07

If a patient contracts an infection while in the hospital, each day of hospitalization increases by 1% the likelihood that the infection will be multidrug-resistant, according to research presented at the 54th Interscience Conference on Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy (ICAAC) an infectious disease meeting of the American Society for Microbiology.

Researchers from the Medical University of South Carolina gathered and analyzed historical data from 949 documented cases of Gram-negative infection at their academic medical center. In the first few days of hospitalization ...

LAST 30 PRESS RELEASES:

Call me invasive: New evidence confirms the status of the giant Asian mantis in Europe

Scientists discover a key mechanism regulating how oxytocin is released in the mouse brain

Public and patient involvement in research is a balancing act of power

Scientists discover “bacterial constipation,” a new disease caused by gut-drying bacteria

DGIST identifies “magic blueprint” for converting carbon dioxide into resources through atom-level catalyst design

COVID-19 vaccination during pregnancy may help prevent preeclampsia

Menopausal hormone therapy not linked to increased risk of death

Chronic shortage of family doctors in England, reveals BMJ analysis

Booster jabs reduce the risks of COVID-19 deaths, study finds

Screening increases survival rate for stage IV breast cancer by 60%

ACC announces inaugural fellow for the Thad and Gerry Waites Rural Cardiovascular Research Fellowship

University of Oklahoma researchers develop durable hybrid materials for faster radiation detection

Medicaid disenrollment spikes at age 19, study finds

Turning agricultural waste into advanced materials: Review highlights how torrefaction could power a sustainable carbon future

New study warns emerging pollutants in livestock and aquaculture waste may threaten ecosystems and public health

Integrated rice–aquatic farming systems may hold the key to smarter nitrogen use and lower agricultural emissions

Hope for global banana farming in genetic discovery

Mirror image pheromones help beetles swipe right

Prenatal lead exposure related to worse cognitive function in adults

Research alert: Understanding substance use across the full spectrum of sexual identity

Pekingese, Shih Tzu and Staffordshire Bull Terrier among twelve dog breeds at risk of serious breathing condition

Selected dog breeds with most breathing trouble identified in new study

Interplay of class and gender may influence social judgments differently between cultures

Pollen counts can be predicted by machine learning models using meteorological data with more than 80% accuracy even a week ahead, for both grass and birch tree pollen, which could be key in effective

Rewriting our understanding of early hominin dispersal to Eurasia

Rising simultaneous wildfire risk compromises international firefighting efforts

Honey bee "dance floors" can be accurately located with a new method, mapping where in the hive forager bees perform waggle dances to signal the location of pollen and nectar for their nestmates

Exercise and nutritional drinks can reduce the need for care in dementia

Michelson Medical Research Foundation awards $750,000 to rising immunology leaders

SfN announces Early Career Policy Ambassadors Class of 2026

[Press-News.org] Dynamic duo takes out the cellular trashSalk scientists identify how immune cells use two critical receptors to clear dead cells from the body, pointing the way to new autoimmune and cancer therapies