(Press-News.org) As humans transform the planet to meet our needs, all sorts of wildlife continue to be pushed aside, including many species that play key roles in Earth's life-support systems. In particular, the transformation of forests into agricultural lands has dramatically reduced biodiversity around the world.

A new study by scientists at Stanford and the University of California, Berkeley, in this week's issue of Science shows that evolutionarily distinct species suffer most heavily in intensively farmed areas. They also found, however, that an extraordinary amount of evolutionary history is sustained in diversified farming systems, which outlines a strategy for balancing agricultural activity and conservation efforts.

"This work is urgent, because humanity is driving about half of all known life to extinction, mostly through agricultural activities to support our vast numbers and meat-rich diets," said Gretchen Daily, the Bing Professor in Environmental Science at Stanford and senior author on the paper. "How are we restructuring the tree of life? What are the implications for people? And what can we do to harmonize farming with nature?"

Calculating evolutionary history

The findings arise from a 12-year research project conducted by Stanford scientists at the intersections of farms and jungles in Costa Rica. Much of the research has focused on how farming practices can impact biodiversity, and has gone so far as to establish the economic value of pest-eating birds and crop-pollinating bees.

The researchers have developed an extraordinarily detailed data set to show human impacts on phylogenetic diversity, a measure of the evolutionary history embodied in wildlife – in this case, birds.

For example, an area inhabited by two species of blackbirds that diverged only a couple of million years ago would have relatively low phylogenetic diversity. The tinamou – a speckled, football-shaped flightless bird – diverged from blackbirds about 100 million years ago, and if it moved into the blackbird's habitat, the phylogenetic diversity of that area would increase significantly.

"If you have an area with lots of closely related species, you won't have a lot of phylogenetic diversity," said co-lead author Luke Frishkoff, a biology doctoral student at Stanford. "The further apart species are on the evolutionary tree, the more phylogenetic diversity your system represents."

The biologists counted almost 120,000 birds, hailing from nearly 500 species, in three different types of habitats in Costa Rica: untouched forest reserves; farmlands with multiple crops and small patches of forest; and intensive farmlands consisting of single crops, such as sugar cane or pineapple, with no adjoining forest areas. They then analyzed the species spread across those types of places and calculated phylogenetic diversity in each.

The findings were bad and good. Not surprisingly, the diversified farmlands supported on average 300 million years of evolutionary history fewer than forests. But they retained an astonishing 600 million more years of evolutionary history than the single crop farms.

"The loss of habitat to agriculture is the primary driver of diversity loss globally, but we hadn't known until now how agriculture affected diversity in an evolutionary context," said study co-lead author Daniel Karp, who began working on this project while he was a doctoral student at Stanford and has continued it as a research fellow at UC Berkeley. "We found that forests outperform agriculture when it comes to supporting a larger range of species that are more distantly related."

But the fact that diversified farms conserve much more phylogenetic diversity than intensive agriculture is encouraging.

"It shows how important it is for biodiversity conservation to surround protected areas with productive forms of diversified agriculture, whenever possible," said co-author Claire Kremen, a professor of environmental science, policy and management at UC Berkeley.

Saving a species

The authors trace the decline of phylogenetic diversity in farmland to the fact that evolutionarily distinct species tend to require niche habitats for survival, and these are often wiped out in developed lands.

While sparrows are adept at finding shelter in farmlands and are happy to eat a variety of seeds found in those areas, the tinamou and other evolutionarily distinct species are highly dependent on jungle habitats and have very specific needs such as diet that can only be met in those environments.

The researchers also outline a theory that human agriculture is simply tipping the scale in favor of species that trace their origin to similar conditions.

"Natural savannahs share some of the characteristics of diversified agriculture," Frishkoff said. "We find some evidence that birds that evolved in those types of habitats, such as blackbirds and sparrows, are doing better in those habitats today."

Preserving biodiversity and phylogenetic history is critical for both healthy ecosystems and prosperous farms, Frishkoff and Karp said. Different species specialize in keeping different pest insects under control, in pollinating the many flowering trees and other plants in tropical landscapes, and then in dispersing their seeds.

"Having just sparrows in an ecosystem is like investing only in technology stocks: If the bubble bursts, you lose," Frishkoff said. "You want to have a truly diversified ecosystem, with an array of species each contributing different benefits. This work really highlights the need to preserve native tropical forest, and whenever possible to make agricultural systems as wildlife friendly as possible. Even relatively modest increases in vegetation on farms can support diverse lineages of birds."

INFORMATION:

Additional co-authors of the study include Elizabeth Hadly, a professor of biology at Stanford; Chase Mendenhall of Stanford; Leithen M'Gonigle of UC Berkeley; and Jim Zook of Unión de Ornitólogos de Costa Rica.

Diversified farming practices might preserve evolutionary diversity of wildlife

2014-09-11

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

You can classify words in your sleep

2014-09-11

When people practice simple word classification tasks before nodding off—knowing that a "cat" is an animal or that "flipu" isn't found in the dictionary, for example—their brains will unconsciously continue to make those classifications even in sleep. The findings, reported in the Cell Press journal Current Biology on September 11, show that some parts of the brain behave similarly whether we are asleep or awake and pave the way for further studies on the processing capacity of our sleeping brains, the researchers say.

"We show that the sleeping brain can be far more ...

Gut microbes determine how well the flu vaccine works

2014-09-11

Annual flu epidemics cause millions of cases of severe illness and up to half a million deaths every year around the world, despite widespread vaccination programs. A study published by Cell Press on September 11th in Immunity reveals that gut microbes play an important role in stimulating protective immune responses to the seasonal flu vaccine in mice, suggesting that differences in the composition of gut microbes in different populations may impact vaccine immunity. The study paves the way for global public health strategies to improve the effectiveness of the flu vaccine. ...

Stem cells help researchers understand how schizophrenic brains function

2014-09-11

Using human induced pluripotent stem cells (hiPSCs), researchers have gained new insight into what may cause schizophrenia by revealing the altered patterns of neuronal signaling associated with this disease. They did so by exposing neurons derived from the hiPSCs of healthy individuals and of patients with schizophrenia to potassium chloride, which triggered these stem cells to release neurotransmitters, such as dopamine, that are crucial for brain function and are linked to various disorders. By discovering a simple method for stimulating hiPSCs to release neurotransmitters, ...

Intestinal bacteria needed for strong flu vaccine responses in mice

2014-09-11

Mice treated with antibiotics to remove most of their intestinal bacteria or raised under sterile conditions have impaired antibody responses to seasonal influenza vaccination, researchers have found.

The findings suggest that antibiotic treatment before or during vaccination may impair responses to certain vaccines in humans. The results may also help to explain why immunity induced by some vaccines varies in different parts of the world.

In a study to be published in Immunity, Bali Pulendran, PhD, and colleagues at Emory University demonstrate a dependency on gut ...

Our microbes are a rich source of drugs, UCSF researchers discover

2014-09-11

Bacteria that normally live in and upon us have genetic blueprints that enable them to make thousands of molecules that act like drugs, and some of these molecules might serve as the basis for new human therapeutics, according to UC San Francisco researchers who report their new discoveries in the September 11, 2014 issue of Cell.

The scientists purified and solved the structure of one of the molecules they identified, an antibiotic they named lactocillin, which is made by a common bacterial species, Lactobacillus gasseri, found in the microbial community within the vagina. ...

Cells put off protein production during times of stress

2014-09-11

DURHAM, N.C. -- Living cells are like miniature factories, responsible for the production of more than 25,000 different proteins with very specific 3-D shapes. And just as an overwhelmed assembly line can begin making mistakes, a stressed cell can end up producing misshapen proteins that are unfolded or misfolded.

Now Duke University researchers in North Carolina and Singapore have shown that the cell recognizes the buildup of these misfolded proteins and responds by reshuffling its workload, much like a stressed out employee might temporarily move papers from an overflowing ...

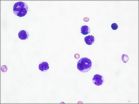

A non-toxic strategy to treat leukemia

2014-09-11

A study comparing how blood stem cells and leukemia cells consume nutrients found that cancer cells are far less tolerant to shifts in their energy supply than their normal counterparts. The results suggest that there could be ways to target leukemia metabolism so that cancer cells die but other cell types are undisturbed.

Harvard Stem Cell Institute scientists at the Massachusetts General Hospital Center for Regenerative Medicine and the Harvard University Department of Stem Cell and Regenerative Biology led the work, published in the journal Cell, in collaboration with ...

Scientists discover neurochemical imbalance in schizophrenia

2014-09-11

Using human induced pluripotent stem cells (hiPSCs), researchers at Skaggs School of Pharmacy and Pharmaceutical Sciences at University of California, San Diego have discovered that neurons from patients with schizophrenia secrete higher amounts of three neurotransmitters broadly implicated in a range of psychiatric disorders.

The findings, reported online Sept. 11 in Stem Cell Reports, represent an important step toward understanding the chemical basis for schizophrenia, a chronic, severe and disabling brain disorder that affects an estimated one in 100 persons at some ...

Diverse gut bacteria associated with favorable ratio of estrogen metabolites

2014-09-11

Washington, DC—Postmenopausal women with diverse gut bacteria exhibit a more favorable ratio of estrogen metabolites, which is associated with reduced risk for breast cancer, compared to women with less microbial variation, according to a new study published in the Endocrine Society's Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism (JCEM).

Since the 1970s, it has been known that in addition to supporting digestion, the intestinal bacteria that make up the gut microbiome influence how women's bodies process estrogen, the primary female sex hormone. The colonies of bacteria ...

Puerto Ricans who inject drugs among Latinos at highest risk of contracting HIV

2014-09-11

Higher HIV risk behaviors and prevalence have been reported among Puerto Rican people who inject drugs (PRPWID) since early in the HIV epidemic. Now that HIV prevention and treatment advances have reduced HIV among PWID in the US, researchers from New York University's Center for Drug Use and HIV Research (CDUHR) examined HIV-related data for PRPWID in Puerto Rico (PR) and Northeastern US (NE) to assess whether disparities among PRPWID continue.

The study, "Addressing the HIV/AIDS epidemic among Puerto Rican people who inject drugs: the Need for a Multi-Region Approach," ...