(Press-News.org) The meteorite impact that spelled doom for the dinosaurs 66 million years ago decimated the evergreens among the flowering plants to a much greater extent than their deciduous peers, according to a study led by UA researchers. The results are published in the journal PLOS Biology.

Applying biomechanical formulas to a treasure trove of thousands of fossilized leaves of angiosperms — flowering plants excluding conifers — the team was able to reconstruct the ecology of a diverse plant community thriving during a 2.2 million-year period spanning the cataclysmic impact event, believed to have wiped out more than half of plant species living at the time.

The researchers found evidence that after the event, fast-growing, deciduous angiosperms had replaced their slow-growing, evergreen peers to a large extent. Living examples of evergreen angiosperms, such as holly and ivy, tend to prefer shade, don't grow very fast and sport dark-colored leaves.

"When you look at forests around the world today, you don't see many forests dominated by evergreen flowering plants," said the study's lead author, Benjamin Blonder, who graduated last year from the lab of UA Professor Brian Enquist with a Ph.D. from the UA's Department of Ecology and Evolutionary Biology and is now the science coordinator at the UA SkySchool. "Instead, they are dominated by deciduous species, plants that lose their leaves at some point during the year."

The study provides much-needed evidence for how the extinction event unfolded in the plant communities at the time, Blonder said. While it was known that the plant species that existed before the impact were different from those that came after, data was sparse on whether the shift in plant assemblages was just a random phenomenon or a direct result of the event.

"If you think about a mass extinction caused by catastrophic event such as a meteorite impacting Earth, you might imagine all species are equally likely to die," Blonder said. "Survival of the fittest doesn't apply — the impact is like a reset button. The alternative hypothesis, however, is that some species had properties that enabled them to survive.

"Our study provides evidence of a dramatic shift from slow-growing plants to fast-growing species," he said. "This tells us that the extinction was not random, and the way in which a plant acquires resources predicts how it can respond to a major disturbance. And potentially this also tells us why we find that modern forests are generally deciduous and not evergreen."

Previously, other scientists found evidence of a dramatic drop in temperature caused by dust from the impact. Under the conditions of such an "impact winter," many plants would have struggled harvesting enough sunlight to maintain their metabolism and growth.

"The hypothesis is that the impact winter introduced a very variable climate," Blonder said. "That would have favored plants that grew quickly and could take advantage of changing conditions, such as deciduous plants."

Blonder, Enquist and their colleagues Dana Royer from Wesleyan University, Kirk Johnson from the Smithsonian National Museum of Natural History and Ian Miller from the Denver Museum of Nature and Science studied a total of about 1,000 fossilized plant leaves collected from a location in southern North Dakota, embedded in rock layers known as the Hell Creek Formation, in what at the time was a lowland floodplain crisscrossed by river channels. The collection consists of more than 10,000 identified plant fossils and is housed primarily at the Denver Museum of Nature and Science.

By analyzing leaves, which convert carbon dioxide from the atmosphere and water into nutrients for the plant, the study followed a new approach that enabled the researchers to predict how plant species used carbon and water, shedding light on the ecological strategies of plant communities long gone, hidden under sediments for many millions of years.

"We measured the mass of a given leaf in relation to its area, which tells us whether the leaf was a chunky, expensive one to make for the plant, or whether it was a more flimsy, cheap one," Blonder explained. "In other words, how much carbon the plant had invested in the leaf."

In addition to the leaves' mass-per-area ratio, Blonder and his coworkers measured the density of the leaves' vein networks.

"When you hold a leaf up to the light, you see a pattern of veins running through it," Blonder said. "That network determines how much water is moved through the leaf. If the density is high, the plant is able to transpire more water, and that means it can acquire carbon faster.

"By comparing the two parameters, we get an idea of resources invested versus resources returned, and that allows us to capture the ecological strategy of the plants we studied long after they went extinct."

Evergreen plants are more likely to invest in leaves that are costly to construct but are well-built and last a long time, Blonder explained, while the leaves of deciduous plants tend to be short-lived but offer high metabolic rates.

"There is a spectrum between fast- and slow-growing species," he said. "There is the 'live fast, die young' strategy and there is the 'slow but steady' strategy. You could compare it to financial strategies investing in stocks versus bonds."

The analyses revealed that while slow-growing evergreens dominated the plant assemblages before the extinction event, fast-growing flowering species had taken their places afterward.

The National Science Foundation awarded Blonder a graduate research fellowship to pursue this research. Additional funding was provided by the Geological Society of America.

Blonder said he was inspired to pursue the research project after seeing a lecture on paleobiology at the UA.

"I had a strong interest in how plants function based on their leaves, and I was fascinated to learn about applying those biomechanical principles to reconstruct ecological functions of the past," he said. "When you hold one of those leaves that is so exquisitely preserved in your hand knowing it's 66 million years old, it's a humbling feeling."

INFORMATION:

Meteorite that doomed dinosaurs remade forests

The impact decimated slow-growing evergreens and made way for fast-growing, deciduous plants, according to a study applying biomechanical analyses to fossilized leaves

2014-09-16

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

A novel therapy for sepsis?

2014-09-16

This release is available in Japanese.

A University of Tokyo research group has discovered that pentatraxin 3 (PTX3), a protein that helps the innate immune system target invaders such as bacteria and viruses, can reduce mortality of mice suffering from sepsis. This discovery may lead to a therapy for sepsis, a major cause of death in developed countries that is fatal in one in four cases.

Professor Takao Hamakubo's group at the Department of Quantitative Biology and Medicine, Research Center for Advanced Science and Technology (RCAST), have shown that PTX3 forms ...

Meteorite that doomed the dinosaurs helped the forests bloom

2014-09-16

66 million years ago, a 10-km diameter chunk of rock hit the Yukatan peninsula near the site of the small town of Chicxulub with the force of 100 teratons of TNT. It left a crater more than 150 km across, and the resulting megatsunami, wildfires, global earthquakes and volcanism are widely accepted to have wiped out the dinosaurs and made way for the rise of the mammals. But what happened to the plants on which the dinosaurs fed?

A new study led by researchers from the University of Arizona reveals that the meteorite impact that spelled doom for the dinosaurs also decimated ...

The genetics of coping with HIV

2014-09-16

We respond to infections in two fundamental ways. One, which has been the subject of intensive research over the years, is "resistance," where the body attacks the invading pathogen and reduces its numbers. Another, which is much less well understood, is "tolerance," where the body tries to minimise the damage done by the pathogen. Now an elegant study using data from a large Swiss cohort of HIV-infected individuals gives us a tantalising glimpse into why some people cope with HIV better than others.

The authors find that tolerance varies substantially between individuals, ...

Point-of-care CD4 testing is economically feasible for HIV care in resource-limited areas

2014-09-16

A new point-of-care test to measure CD4 T-cells, the prime indicator of HIV disease progression, can expedite the process leading from HIV diagnosis to antiretroviral therapy (ART) and improve clinical outcomes. Now a study by Massachusetts General Hospital (MGH) investigators, working in collaboration with colleagues in Mozambique and South Africa, indicates that routine use of point-of-care CD4 testing at the time of HIV diagnosis could be cost effective in countries where health care and other resources are severely limited. Their analysis is being published in the ...

Nanoribbon film keeps glass ice-free

2014-09-16

Rice University scientists who created a deicing film for radar domes have now refined the technology to work as a transparent coating for glass.

The new work by Rice chemist James Tour and his colleagues could keep glass surfaces from windshields to skyscrapers free of ice and fog while retaining their transparency to radio frequencies (RF).

The technology was introduced this month in the American Chemical Society journal Applied Materials and Interfaces.

The material is made of graphene nanoribbons, atom-thick strips of carbon created by splitting nanotubes, ...

Journal of Clinical Psychiatry: Long-term benefit of NeuroStar TMS Therapy in depression

2014-09-16

Malvern, Pennsylvania, September 16, 2014 – Neuronetics, Inc., today announced that results of a study designed to assess the long-term effectiveness of NeuroStar TMS Therapy in adult patients with Major Depressive Disorder (MDD) who have failed to benefit from prior treatment with antidepressant medications, were published online in The Journal of Clinical Psychiatry. The study found that TMS treatment with the NeuroStar TMS Therapy System induced statistically and clinically meaningful response and remission in patients with treatment resistant MDD during the acute phase ...

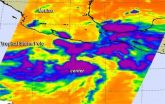

NASA spots center of Typhoon Kalmaegi over Hainan Island, headed for Vietnam

2014-09-16

NASA's Aqua satellite saw Typhoon Kalmaegi's center near northern Hainan Island, China when it passed overhead on September 16 at 06:00 UTC (2 a.m. EDT). Hours later, the storm crossed the Gulf of Tonkin, the body of water that separates Hainan Island from Vietnam, and was making landfall there at 11:30 a.m. EDT.

The Moderate Resolution Imaging Spectroradiometer or MODIS instrument aboard Aqua captured a picture of the typhoon that shows the center near the northern end of Hainan Island, China, while the storm stretches over the mainland of southeastern China, east into ...

Computerized emotion detector

2014-09-16

Face recognition software measures various parameters in a mug shot, such as the distance between the person's eyes, the height from lip to top of their nose and various other metrics and then compares it with photos of people in the database that have been tagged with a given name. Now, research published in the International Journal of Computational Vision and Robotics looks to take that one step further in recognizing the emotion portrayed by a face.

Dev Drume Agrawal, Shiv Ram Dubey and Anand Singh Jalal of the GLA University, in Mathura, Uttar Pradesh, India, suggest ...

Newborn Tropical Storm Polo gives a NASA satellite a 'cold reception'

2014-09-16

The AIRS instrument aboard NASA's Aqua satellite uses infrared light to read cloud top temperatures in tropical cyclones. When Aqua passed over newborn Tropical Storm Polo off of Mexico's southwestern coast it got a "cold reception" when infrared data saw some very cold cloud top temperatures and strong storms within that hint at intensification.

Polo formed close enough to land to trigger a Tropical Storm Watch for the southwestern coast of Mexico. The watch was issued by the government of Mexico on September 16 and extends from Zihuatanejo to Cabo Corrientes, Mexico. ...

EARTH Magazine: The Bay Area's next 'big one could strike as a series of quakes

2014-09-16

Alexandria, Va. — Most people are familiar with the Great 1906 San Francisco Earthquake and are aware of the earthquake risk posed to the Bay Area — and much of California — by the San Andreas Fault. Most people are not aware, however, that a cluster of large earthquakes struck the San Andreas and quite a few nearby faults in the 17th and 18th centuries. That cluster, according to new research, released about the same amount of energy throughout the Bay Area as the 1906 quake. Thus, it appears that the accumulated stress on the region's faults could be released in a series ...

LAST 30 PRESS RELEASES:

Novel camel antimicrobial peptides show promise against drug-resistant bacteria

Scientists discover why we know when to stop scratching an itch

A hidden reason inner ear cells die – and what it means for preventing hearing loss

Researchers discover how tuberculosis bacteria use a “stealth” mechanism to evade the immune system

New microscopy technique lets scientists see cells in unprecedented detail and color

Sometimes less is more: Scientists rethink how to pack medicine into tiny delivery capsules

Scientists build low-cost microscope to study living cells in zero gravity

The Biophysical Journal names Denis V. Titov the 2025 Paper of the Year-Early Career Investigator awardee

Scientists show how your body senses cold—and why menthol feels cool

Scientists deliver new molecule for getting DNA into cells

Study reveals insights about brain regions linked to OCD, informing potential treatments

Does ocean saltiness influence El Niño?

2026 Young Investigators: ONR celebrates new talent tackling warfighter challenges

Genetics help explain who gets the ‘telltale tingle’ from music, art and literature

Many Americans misunderstand medical aid in dying laws

Researchers publish landmark infectious disease study in ‘Science’

New NSF award supports innovative role-playing game approach to strengthening research security in academia

Kumar named to ACMA Emerging Leaders Program for 2026

AI language models could transform aquatic environmental risk assessment

New isotope tools reveal hidden pathways reshaping the global nitrogen cycle

Study reveals how antibiotic structure controls removal from water using biochar

Why chronic pain lasts longer in women: Immune cells offer clues

Toxic exposure creates epigenetic disease risk over 20 generations

More time spent on social media linked to steroid use intentions among boys and men

New study suggests a “kick it while it’s down” approach to cancer treatment could improve cure rates

Milken Institute, Ann Theodore Foundation launch new grant to support clinical trial for potential sarcoidosis treatment

New strategies boost effectiveness of CAR-NK therapy against cancer

Study: Adolescent cannabis use linked to doubling risk of psychotic and bipolar disorders

Invisible harms: drug-related deaths spike after hurricanes and tropical storms

Adolescent cannabis use and risk of psychotic, bipolar, depressive, and anxiety disorders

[Press-News.org] Meteorite that doomed dinosaurs remade forestsThe impact decimated slow-growing evergreens and made way for fast-growing, deciduous plants, according to a study applying biomechanical analyses to fossilized leaves