(Press-News.org) Paratuberculosis, also known as Johne's disease, is caused by the bacterium Mycobacterium avium subspecies paratuberculosis (MAP). In Austria, there is a legal obligation to report the disease. Paratuberculosis mainly affects ruminants and causes treatment-resistant diarrhoea and wasting among affected animals. The disease can cause considerable economic losses for commercial farms. The animals produce less milk, exhibit fertility problems and are more susceptible to other conditions such as udder inflammation.

To date there has been no treatment for paratuberculosis. Affected animals must be reported and sacrificed. The meat of affected animals is not suitable for consumption and must be disposed of.

The disease usually manifests two to three years after the initial infection. In some cases, it can even take up to ten years before the disease becomes apparent. During this time, infected animals shed the bacteria, putting the health of the entire herd at risk.

Lymphatic Fluid Suitable for Early Testing

The bacterium MAP enters the body via the intestine and is passed to the animal's macrophages. These immune cells then migrate through the lymphatic fluid into the lymph nodes, the blood and other organs. Laboratory testing currently looks at faeces, milk and blood of animals suspected of being infected. First author Lorenz Khol of the Clinic for Ruminants at the Vetmeduni Vienna, in cooperation with the College of Veterinary Medicine at the University of Florida, developed a possible alternative method for early diagnosis of the infection. For the test, Khol takes fluid from the lymph vessels at the udder of the animals. Just a few millilitres are enough to detect the bacterium using PCR (polymerase chain reaction) in the lymph.

"Taking lymphatic fluid from cattle is not easy, but it can be performed effortlessly with some practice. The longitudinal vessels lie next to the veins under the skin of the udder and can only be punctured during lactation. As the macrophages can be found in the lymphatic fluid first, we believe that an infection can be diagnosed here substantially earlier and more quickly than with today's usual methods," says Khol.

Lymph Tests Positive More Often Than Faeces, Blood or Milk

The scientists tested a total of 86 cows from different farms exhibiting symptoms of diarrhoea and weight loss. The lymph analysis yielded significantly more positive results than the analysis using faeces, blood or milk. "This is an indication of the higher sensitivity of our method. After one year, about 70 percent of all animals which were tested positive via lymph-PCR had been culled from their herds. These animals had developed various diseases or a reduced performance that made it necessary to remove the animals from the farm. In comparison, cows with a negative lymph result showed a 27 percent culling rate after one year only.

"The results show that the method is a promising one. We must still improve the technique, however, in order to increase the reliability of the results. The fact that there is no treatment for this disease makes comprehensive early diagnosis especially important," Khol explains.

INFORMATION:

The article "Lymphatic fluid for the detection of Mycobacterium avium subsp. paratuberculosis in cows by PCR, compared to fecal sampling and detection of antibodies in blood and milk", by Johannes Lorenz Khol, Pablo J. Pinedo, Claus D. Buergelt, Laura M. Neumann and D. Owen Rae was published in the Journal Veterinary Microbiology veröffentlicht. DOI: 10.1016/j.vetmic.2014.05.022

http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0378113514002673

About the University of Veterinary Medicine, Vienna

The University of Veterinary Medicine, Vienna in Austria is one of the leading academic and research institutions in the field of Veterinary Sciences in Europe. About 1,200 employees and 2,300 students work on the campus in the north of Vienna which also houses five university clinics and various research sites. Outside of Vienna the university operates Teaching and Research Farms. http://www.vetmeduni.ac.at

Scientific Contact

Dr. Johannes Lorenz Khol

Clinical Unit of Ruminant

University of Veterinary Medicine Vienna (Vetmeduni Vienna)

T +43 1 25077-5205

johannes.khol@vetmeduni.ac.at

Released By

Heike Hochhauser

Public Relations

University of Veterinary Medicine Vienna (Vetmeduni Vienna)

T +43 1 25077-1151

heike.hochhauser@vetmeduni.ac.at

Lymphatic fluid used for first time to detect bovine paratuberculosis

2014-09-19

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

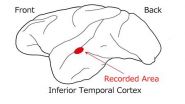

Neurons express 'gloss' using three perceptual parameters

2014-09-19

Japanese researchers showed monkeys a number of images representing various glosses and then they measured the responses of 39 neurons by using microelectrodes. They found that a specific population of neurons changed the intensities of the responses linearly according to either the contrast-of-highlight, sharpness-of-highlight, or brightness of the object. This shows that these 3 perceptual parameters are used as parameters when the brain recognizes a variety of glosses. They also found that different parameters are represented by different populations of neurons. This ...

Environmental pollutants make worms susceptible to cold

2014-09-19

Imagine you are a species which over thousands of years has adapted to the arctic cold, and then you get exposed to a substance that makes the cold dangerous for you.

This is happening to the small white worm Enchytraeus albidus, and the cold provoking substance, called nonylphenol, comes from the use of certain detergents, pesticides and cosmetics.

Nonylphenol is suspected of being a endocrine disruptor, but when entering the worm it has another dangerous effect: It inhibits the worm's ability to protect the cells in its body from cold damage.

Enchytraeus albidus ...

Quick-change materials break the silicon speed limit for computers

2014-09-19

The present size and speed limitations of computer processors and memory could be overcome by replacing silicon with 'phase-change materials' (PCMs), which are capable of reversibly switching between two structural phases with different electrical states – one crystalline and conducting and the other glassy and insulating – in billionths of a second.

Modelling and tests of PCM-based devices have shown that logic-processing operations can be performed in non-volatile memory cells using particular combinations of ultra-short voltage pulses, which is not possible with silicon-based ...

Milestone in chemical studies of superheavy elements

2014-09-19

An international collaboration led by research groups from Mainz and Darmstadt, Germany, has achieved the synthesis of a new class of chemical compounds for superheavy elements at the RIKEN Nishina Center for Accelerator-based Research (RNC) in Japan. For the first time, a chemical bond was established between a superheavy element – seaborgium (element 106) in the present study – and a carbon atom. Eighteen atoms of seaborgium were converted into seaborgium hexacarbonyl complexes, which include six carbon monoxide molecules bound to the seaborgium. Its gaseous properties ...

Technique to model infections shows why live vaccines may be most effective

2014-09-19

Vaccines against Salmonella that use a live, but weakened, form of the bacteria are more effective than those that use only dead fragments because of the particular way in which they stimulate the immune system, according to research from the University of Cambridge published today in the journal PLOS Pathogens.

The BBSRC-funded researchers used a new technique that they have developed where several populations of bacteria, each of which has been individually tagged with a unique DNA sequence, are administered to the same host (in this case, a mouse). This allows the ...

How pneumonia bacteria can compromise heart health

2014-09-19

Bacterial pneumonia in adults carries an elevated risk for adverse cardiac events (such as heart failure, arrhythmias, and heart attacks) that contribute substantially to mortality—but how the heart is compromised has been unclear. A study published on September 18th in PLOS Pathogens now demonstrates that Streptococcus pneumoniae, the bacterium responsible for most cases of bacterial pneumonia, can invade the heart and cause the death of heart muscle cells.

Carlos Orihuela, from the University of Texas Health Science Center in San Antonio, USA, and colleagues initially ...

Human sense of fairness evolved to favor long-term cooperation

2014-09-19

VIDEO:

This is a video describing the ultimatum game in chimpanzees.

Click here for more information.

ATLANTA—The human response to unfairness evolved in order to support long-term cooperation, according to a research team from Georgia State University and Emory University.

Fairness is a social ideal that cannot be measured, so to understand the evolution of fairness in humans, Dr. Sarah Brosnan of Georgia State's departments of Psychology and Philosophy, the Neuroscience Institute ...

Nuclear spins control current in plastic LED

2014-09-19

SALT LAKE CITY, Sept. 18, 2014 – University of Utah physicists read the subatomic "spins" in the centers or nuclei of hydrogen isotopes, and used the data to control current that powered light in a cheap, plastic LED – at room temperature and without strong magnetic fields.

The study – published in Friday's issue of the journal Science – brings physics a step closer to practical machines that work "spintronically" as well as electronically: superfast quantum computers, more compact data storage devices and plastic or organic light-emitting diodes, or OLEDs, more efficient ...

Changes in coastal upwelling linked to temporary declines in marine ecosystem

2014-09-19

In findings of relevance to both conservationists and the fishing industry, new research links short-term reductions in growth and reproduction of marine animals off the California Coast to increasing variability in the strength of coastal upwelling currents — currents which historically supply nutrients to the region's diverse ecosystem.

Along the west coast of North America, winds lift deep, nutrient-rich water into sunlit surface layers, fueling vast phytoplankton blooms that ultimately support fish, seabirds and marine mammals.

The new study, led by Bryan Black ...

World population to keep growing this century, hit 11 billion by 2100

2014-09-19

Using modern statistical tools, a new study led by the University of Washington and the United Nations finds that world population is likely to keep growing throughout the 21st century. The number of people on Earth is likely to reach 11 billion by 2100, the study concludes, about 2 billion higher than some previous estimates.

The paper published online Sept. 18 in the journal Science includes the most up-to-date estimates for future world population, as well as a new method for creating such estimates.

"The consensus over the past 20 years or so was that world population, ...