(Press-News.org) Call it the Jimmy Durante of dinosaurs – a newly discovered hadrosaur with a truly distinctive nasal profile. The new dinosaur, named Rhinorex condrupus by paleontologists from North Carolina State University and Brigham Young University, lived in what is now Utah approximately 75 million years ago during the Late Cretaceous period.

Rhinorex, which translates roughly into "King Nose," was a plant-eater and a close relative of other Cretaceous hadrosaurs like Parasaurolophus and Edmontosaurus. Hadrosaurs are usually identified by bony crests that extended from the skull, although Edmontosaurus doesn't have such a hard crest (paleontologists have discovered that it had a fleshy crest). Rhinorex also lacks a crest on the top of its head; instead, this new dinosaur has a huge nose.

Terry Gates, a joint postdoctoral researcher with NC State and the North Carolina Museum of Natural Sciences, and colleague Rodney Sheetz from the Brigham Young Museum of Paleontology, came across the fossil in storage at BYU. First excavated in the 1990s from Utah's Neslen formation, Rhinorex had been studied primarily for its well-preserved skin impressions. When Gates and Sheetz reconstructed the skull, they realized that they had a new species.

"We had almost the entire skull, which was wonderful," Gates says, "but the preparation was very difficult. It took two years to dig the fossil out of the sandstone it was embedded in – it was like digging a dinosaur skull out of a concrete driveway."

Based on the recovered bones, Gates estimates that Rhinorex was about 30 feet long and weighed over 8,500 lbs. It lived in a swampy estuarial environment, about 50 miles from the coast. Rhinorex is the only complete hadrosaur fossil from the Neslen site, and it helps fill in some gaps about habitat segregation during the Late Cretaceous.

"We've found other hadrosaurs from the same time period but located about 200 miles farther south that are adapted to a different environment," Gates says. "This discovery gives us a geographic snapshot of the Cretaceous, and helps us place contemporary species in their correct time and place. Rhinorex also helps us further fill in the hadrosaur family tree."

When asked how Rhinorex may have benefitted from a large nose Gates said, "The purpose of such a big nose is still a mystery. If this dinosaur is anything like its relatives then it likely did not have a super sense of smell; but maybe the nose was used as a means of attracting mates, recognizing members of its species, or even as a large attachment for a plant-smashing beak. We are already sniffing out answers to these questions."

The researchers' results appear in the Journal of Systematic Palaeontology.

INFORMATION:

"A new species of saurolophine hadrosaurid (Dinosauria: Ornithopoda) from the Campanian of Utah, North America"

Authors

Terry Gates, North Carolina State University and the NC Museum of Natural Sciences; Rodney Sheetz, Brigham Young University

Published

Online in the Journal of Systematic Palaeontology

Abstract

A new species of hadrosaurid is described from the Upper Cretaceous Neslen Formation of central Utah. Rhinorex condrupus is diagnosed on the basis of two unique traits, a hook-shaped projection of the nasal anteroventral process and dorsal projection of the posteroventral process of the premaxilla, and further differentiated from other hadrosaurid species on the morphology of the nasal (large nasal boss on posterodrosal corner of circumnarial fossa, small protuberences on anterior process, absence of nasal arch), jugal (vertical postorbital process), postorbital (high degree of flexion present on posterior process), and squamosal (inclined anterolateral processes). This new taxon was discovered in estuarine sediments dating to approximately 75 Ma and just 250 km north of the prolific dinosaur bearing strata of the Kaiparowits Formation,possibly overlapping in time with Gryposaurus monumentensis. Phylogenetic parsimony and Bayesian analyses associate this new taxon with the Gryposaurus clade, even though the type specimen does not possess the diagnostic nasal hump of the latter genus. Comparison with phylogenetic analyses from other studies show that currently consensus exists between general structure of the hadrosaurid evolutionary tree, but at closer examination there is little agreement among species relationships.

New hadrosaur noses into spotlight

2014-09-19

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

Researchers discover new gene responsible for traits involved in diabetes

2014-09-19

A collaborative research team led by Medical College of Wisconsin (MCW) scientists has identified a new gene associated with fasting glucose and insulin levels in rats, mice and in humans. The findings are published in the September issue of Genetics.

Leah Solberg Woods, Ph.D., associate professor of pediatrics at MCW and a researcher in the Children's Hospital of Wisconsin Research Institute, led the study and is the corresponding author of the paper.

The authors of the paper identified a gene called Tpcn2 in which a variant was associated with fasting glucose levels ...

Don't cry wolf: Drivers fed up with slowing down at inactive roadwork sites

2014-09-19

The results of the QUT Centre for Accident Research & Road Safety - Queensland (CARRS-Q) study have been presented at the Occupational Safety in Transport Conference (OSIT) which is being held on the Gold Coast and finishes today.

Dr Ross Blackman, a CARRS-Q road safety researcher, said speed limit credibility was being put at risk when reduced speed limits and related traffic controls remained in place at inactive roadwork sites.

"It's seen as crying wolf. If people are asked to slow down at roadwork sites but find there is no roadwork being undertaken they become ...

Long-distance communication from leaves to roots

2014-09-19

Leguminous plants are able to grow well in infertile land, and bear many beans that are important to humans. The reason for this is because most legumes have a symbiotic relationship with bacteria, called rhizobia, that can fix nitrogen in the air and then supply the host plant with ammonia as a nutrient.

The plants create symbiotic organs called nodules in their roots. However, if too many root nodules are made it will adversely affect the growth of the plants, because the energy cost of maintaining excessive nodules is too large. Therefore legumes must have a mechanism ...

Lymphatic fluid used for first time to detect bovine paratuberculosis

2014-09-19

Paratuberculosis, also known as Johne's disease, is caused by the bacterium Mycobacterium avium subspecies paratuberculosis (MAP). In Austria, there is a legal obligation to report the disease. Paratuberculosis mainly affects ruminants and causes treatment-resistant diarrhoea and wasting among affected animals. The disease can cause considerable economic losses for commercial farms. The animals produce less milk, exhibit fertility problems and are more susceptible to other conditions such as udder inflammation.

To date there has been no treatment for paratuberculosis. ...

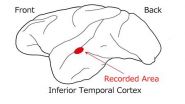

Neurons express 'gloss' using three perceptual parameters

2014-09-19

Japanese researchers showed monkeys a number of images representing various glosses and then they measured the responses of 39 neurons by using microelectrodes. They found that a specific population of neurons changed the intensities of the responses linearly according to either the contrast-of-highlight, sharpness-of-highlight, or brightness of the object. This shows that these 3 perceptual parameters are used as parameters when the brain recognizes a variety of glosses. They also found that different parameters are represented by different populations of neurons. This ...

Environmental pollutants make worms susceptible to cold

2014-09-19

Imagine you are a species which over thousands of years has adapted to the arctic cold, and then you get exposed to a substance that makes the cold dangerous for you.

This is happening to the small white worm Enchytraeus albidus, and the cold provoking substance, called nonylphenol, comes from the use of certain detergents, pesticides and cosmetics.

Nonylphenol is suspected of being a endocrine disruptor, but when entering the worm it has another dangerous effect: It inhibits the worm's ability to protect the cells in its body from cold damage.

Enchytraeus albidus ...

Quick-change materials break the silicon speed limit for computers

2014-09-19

The present size and speed limitations of computer processors and memory could be overcome by replacing silicon with 'phase-change materials' (PCMs), which are capable of reversibly switching between two structural phases with different electrical states – one crystalline and conducting and the other glassy and insulating – in billionths of a second.

Modelling and tests of PCM-based devices have shown that logic-processing operations can be performed in non-volatile memory cells using particular combinations of ultra-short voltage pulses, which is not possible with silicon-based ...

Milestone in chemical studies of superheavy elements

2014-09-19

An international collaboration led by research groups from Mainz and Darmstadt, Germany, has achieved the synthesis of a new class of chemical compounds for superheavy elements at the RIKEN Nishina Center for Accelerator-based Research (RNC) in Japan. For the first time, a chemical bond was established between a superheavy element – seaborgium (element 106) in the present study – and a carbon atom. Eighteen atoms of seaborgium were converted into seaborgium hexacarbonyl complexes, which include six carbon monoxide molecules bound to the seaborgium. Its gaseous properties ...

Technique to model infections shows why live vaccines may be most effective

2014-09-19

Vaccines against Salmonella that use a live, but weakened, form of the bacteria are more effective than those that use only dead fragments because of the particular way in which they stimulate the immune system, according to research from the University of Cambridge published today in the journal PLOS Pathogens.

The BBSRC-funded researchers used a new technique that they have developed where several populations of bacteria, each of which has been individually tagged with a unique DNA sequence, are administered to the same host (in this case, a mouse). This allows the ...

How pneumonia bacteria can compromise heart health

2014-09-19

Bacterial pneumonia in adults carries an elevated risk for adverse cardiac events (such as heart failure, arrhythmias, and heart attacks) that contribute substantially to mortality—but how the heart is compromised has been unclear. A study published on September 18th in PLOS Pathogens now demonstrates that Streptococcus pneumoniae, the bacterium responsible for most cases of bacterial pneumonia, can invade the heart and cause the death of heart muscle cells.

Carlos Orihuela, from the University of Texas Health Science Center in San Antonio, USA, and colleagues initially ...