(Press-News.org) Over 500 million people worldwide carry a genetic mutation that disables a common metabolic protein called ALDH2. The mutation, which predominantly occurs in people of East Asian descent, leads to an increased risk of heart disease and poorer outcomes after a heart attack. It also causes facial flushing when carriers drink alcohol.

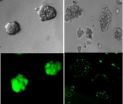

Now researchers at the Stanford University School of Medicine have learned for the first time specifically how the mutation affects heart health. They did so by comparing heart muscle cells made from induced pluripotent stem cells, or iPS cells, from people with the mutation versus those without the mutation. IPS cells are created in the laboratory from specialized adult cells like skin. They are "pluripotent," meaning they can be coaxed to become any cell in the body.

"This study is one of the first to show that we can use iPS cells to study ethnic-specific differences among populations," said Joseph Wu, MD, PhD, director of the Stanford Cardiovascular Institute and professor of cardiovascular medicine and of radiology.

"These findings may help us discover new therapeutic paths for heart disease for carriers of this mutation," said Wu. "In the future, I believe we will have banks of iPS cells generated from many different ethnic groups. Drug companies or clinicians can then compare how members of different ethnic groups respond to drugs or diseases, or study how one group might differ from another, or tailor specific drugs to fit particular groups."

The findings are described in a paper that will be published Sept. 24 in Science Translational Medicine. Wu and Daria Mochly-Rosen, PhD, professor of chemical and systems biology, are co-senior authors of the paper, and postdoctoral scholar Antje Ebert, PhD, is the lead author.

ALDH2 and cell death

The study showed that the ALDH2 mutation affects heart health by controlling the survival decisions cells make during times of stress. It is the first time ALDH2, which is involved in many common metabolic processes in cells of all types, has been shown to play a role in cell survival. In particular, ALDH2 activity, or the lack of it, influences whether a cell enters a state of programmed cell death called apoptosis in response to stressful growing conditions.

The use of heart muscle cells derived from iPS cells has opened important doors for scientists because tissue samples can be easily obtained and maintained in the laboratory for study. Until recently, researchers had to confine their studies to genetically engineered mice or to human heart cells obtained through a heart biopsy, an invasive procedure that yields cells which are difficult to keep alive long term in the laboratory.

"People have studied the enzyme ALDH2 for many years in animal models," said Ebert. "But there are many significant differences between mice and humans. Now we can study actual human heart muscle cells, conveniently grown in the lab."

The iPS cells in this study were created from skin samples donated by 10 men, ages 21-22, of East Asian descent.

About 8 percent of the world's population carries the mutation in one of their two copies of the ALDH2 gene, which encodes a protein known as aldehyde dehydrogenase 2. The mutation in the gene short-circuits the production of the functional protein. (Because most carriers have one normal and one mutated copy of the gene, they are not completely lacking in the functional ALDH2 protein.)

One of ALDH2's many jobs in a cell is to seek out and neutralize toxic aldehydes, harmful substances caused by a class of compounds called reactive oxygen species. One toxic aldehyde, called 4HNE, causes the accumulation of yet more reactive oxygen species. Left to their own devices, high levels of reactive oxygen species can signal a cell to undergo programmed cell death in response to stress, such as the lack of oxygen that mimics what happens during a heart attack.

In this study, Ebert and her colleagues first studied the skin cells obtained from the volunteers. Five of the 10 volunteers had an ALDH2 mutation; the other five did not. The researchers found that skin cells with the mutation in the ALDH2 gene had strongly decreased function of the ALDH2 protein compared with the cells without the mutation. The mutated cells also had significantly higher amounts of reactive oxygen species, and grew more slowly than the other cells.

They next created iPS cells from the donated skin samples, and stimulated the iPS cells to become heart muscle cells called cardiomyocytes. They then compared how the newly created cardiomyocytes responded to low-oxygen conditions. Cardiomyocytes with the ALDH2 mutation had higher levels of reactive oxygen species in response to low oxygen levels than those without the mutation, but this difference could be alleviated by treating the cells with a compound that boosts activity of the ALDH2 protein in patients with one unmutated copy of the gene.

Cells with the mutation also were less viable and more likely to undergo programmed cell death than were cells without the mutation. Further study has identified the involvement of a protein called JNK that is activated by high levels of reactive oxygen species. JNK activates a protein called c-Jun known to stimulate programmed cell death.

"This is an entirely new function attributed to this well-known metabolic enzyme," said Ebert. "It's the first time ALDH2 has been shown to play a role in cell survival. Now we have come to understand that when the ALDH2 gene is mutated, cells are more likely to undergo programmed cell death, causing tissue damage."

Establishing biobank of diverse iPS cells

The researchers plan to continue their studies of ALDH2 and its role in maintaining heart health. They would like to investigate further the signaling mechanisms and structural DNA changes that may occur in the presence of the mutation in the ALDH2 gene. This will also allow research on drugs that would increase the activity of the ALDH2 protein in carriers with one good copy and one mutated copy of the gene, which might become a useful therapy for coronary artery disease and heart attacks.

"With our current state of knowledge, it is very likely that we are ignorant of many functions that ALDH2 has in physiological processes," said Ebert.

Wu is working to start a biobank at the Stanford Cardiovascular Institute of iPS cells from about 1,000 people of many different ethnic backgrounds and health histories. "This is one of my main priorities," he said. "For example, in California, we boast one of the most diverse populations on Earth. We'd like to include male and female patients of major representative ethnicities, age ranges and cardiovascular histories. This will allow us to conduct 'clinical trials in a dish' on these cells, a very powerful new approach, to learn which therapies work best for each group. This would help physicians to understand for the first time disease process at a population level through observing these cells as surrogates."

INFORMATION:

Other Stanford co-authors are postdoctoral scholars Kazuki Kodo, MD, PhD, Ping Liang, PhD, HaoDi Wu, PhD, Bruno Huber, MD, Johannes Riegler, PhD, Jared Churko, PhD, Jaecheol Lee, PhD, Patricia de Almeida, PhD, DVM, Feng Lan, PhD, and Sebastian Diecke, PhD; instructor Paul Burridge, PhD; and Joseph Gold, PhD, assistant director of translational research at the Stanford Cardiovascular Institute.

The research was supported by the American Heart Association, the National Institutes of Health (grants R01HL113006, U01HL099776, R24HL117756, P01GM099130, and AA11147), the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft and the Fondation Leducq.

Wu is a cofounder of Stem Cell Theranostics. Mochly-Rosen is the founder of ALDEA Pharmaceuticals, a company that is developing a number of small-molecule modulators of ALDH activity for medical use. However, she has no role in the company. The research in her lab is supported only by the NIH and not disclosed to the company.

Information about Stanford's Department of Medicine, which also supported the work, is available at http://medicine.stanford.edu.

Print media contact: Krista Conger at (650) 725-5371 (kristac@stanford.edu)

Broadcast media contact: Margarita Gallardo at (650) 723-7897 (mjgallardo@stanford.edu)

The Stanford University School of Medicine consistently ranks among the nation's top medical schools, integrating research, medical education, patient care and community service. For more news about the school, please visit http://mednews.stanford.edu. The medical school is part of Stanford Medicine, which includes Stanford Health Care and Lucile Packard Children's Hospital Stanford. For information about all three, please visit http://med.stanford.edu.

Stanford scientists use stem cells to learn how common mutation in Asians affects heart health

2014-09-24

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

The plus side of population aging

2014-09-24

Around the world, people are living longer and having fewer children, leading to a population that is older, on average, than in the past. On average, life expectancy in developed countries has risen at a pace of three months per year, and fertility has fallen below replacement rate in the majority of Europe and other developed countries.

Most academic discussion of this trend has so far focused on potential problems it creates, including challenges to pension systems, economic growth, and healthcare costs.

But according to a new study published today in the journal PLOS ...

Brain scans reveal 'gray matter' differences in media multitaskers

2014-09-24

Simultaneously using mobile phones, laptops and other media devices could be changing the structure of our brains, according to new University of Sussex research.

A study published today (24 September) reveals that people who frequently use several media devices at the same time have lower grey-matter density in one particular region of the brain compared to those who use just one device occasionally.

The research supports earlier studies showing connections between high media-multitasking activity and poor attention in the face of distractions, along with emotional ...

Colorado's Front Range fire severity not much different than past, say CU study

2014-09-24

The perception that Colorado's Front Range wildfires are becoming increasingly severe does not hold much water scientifically, according to a massive new study led by the University of Colorado Boulder and Humboldt State University in Arcata, Calif.

The study authors, who looked at 1.3 million acres of ponderosa pine and mixed conifer forest from Teller County west of Colorado Springs through Larimer County west and north of Fort Collins, reconstructed the timing and severity of past fires using fire-scarred trees and tree-ring data going back to the 1600s. Only 16 percent ...

New dinosaur from New Mexico has relatives in Alberta

2014-09-24

(Edmonton) A newly discovered armoured dinosaur from New Mexico has close ties to the dinosaurs of Alberta, say University of Alberta paleontologists involved in the research.

From 76 to 66 million years ago, Alberta was home to at least five species of ankylosaurid dinosaurs, the group that includes club-tailed giants like Ankylosaurus. But fewer ankylosaurids are known from the southern parts of North America. The new species, Ziapelta sanjuanensis, was discovered in 2011 in the Bisti/De-na-zin Wilderness area of New Mexico by a team from the New Mexico Museum of Natural ...

A way to kill chemo-resistant ovarian cancer cells: Cut down its protector

2014-09-24

Ottawa, Canada – September 24, 2014 – Ovarian cancer is the most deadly gynecological cancer, claiming the lives of more than 50% of women who are diagnosed with the disease. A study involving Ottawa and Taiwan researchers, published today in the influential Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (PNAS), provides new insight into why ovarian cancer is often resistant to chemotherapy, as well as a potential way to improve its diagnosis and treatment.

It is estimated that 2,700 Canadian women will be diagnosed with ovarian cancer in 2014 and that 1,750 Canadian ...

Star Trekish, rafting scientists make bold discovery on Fraser River

2014-09-24

A Simon Fraser University-led team behind a new discovery has "…had the vision to go, like Star Trek, where no one has gone before: to a steep and violent bedrock canyon, with surprising results."

That comment comes from a reviewer about a truly groundbreaking study just published in the journal Nature.

Scientists studying river flow in bedrock canyons for the first time have discovered that previous conceptions of flow and incision in bedrock-rivers are wrong.

SFU geography professor Jeremy Venditti led the team of SFU, University of Ottawa and University of British ...

Bacterial 'communication system' could be used to stop and kill cancer cells, MU study finds

2014-09-24

COLUMBIA, Mo. – Cancer, while always dangerous, truly becomes life-threatening when cancer cells begin to spread to different areas throughout the body. Now, researchers at the University of Missouri have discovered that a molecule used as a communication system by bacteria can be manipulated to prevent cancer cells from spreading. Senthil Kumar, an assistant research professor and assistant director of the Comparative Oncology and Epigenetics Laboratory at the MU College of Veterinary Medicine, says this communication system can be used to "tell" cancer cells how to act, ...

Study: Biochar alters water flow to improve sand and clay

2014-09-24

As more gardeners and farmers add ground charcoal, or biochar, to soil to both boost crop yields and counter global climate change, a new study by researchers at Rice University and Colorado College could help settle the debate about one of biochar's biggest benefits -- the seemingly contradictory ability to make clay soils drain faster and sandy soils drain slower.

The study, available online this week in the journal PLOS ONE, offers the first detailed explanation for the hydrological mystery.

"Understanding the controls on water movement through biochar-amended soils ...

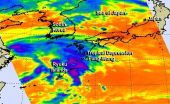

NASA sees the end of post-depression Fung-Wong

2014-09-24

Tropical Depression Fung-Wong looked more like a cold front on infrared satellite imagery from NASA than it did a low pressure area with a circulation.

NASA's Aqua satellite passed over Tropical Depression Fung-Wong on Sept. 23 at 12:23 a.m. EDT. The Atmospheric Infrared Sounder or AIRS instrument that flies aboard Aqua gathered infrared temperature data on the storm's clouds. The data was false-colored at NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory, Pasadena, California and showed that the storm resembled a frontal system more than a depression. The center of circulation was southwest ...

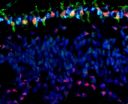

How a single, genetic change causes retinal tumors in young children

2014-09-24

Retinoblastoma is a childhood retinal tumor usually affecting children one to two years of age. Although rare, it is the most common malignant tumor of the eye in children. Left untreated, retinoblastoma can be fatal or result in blindness. It has also played a special role in understanding cancer, because retinoblastomas have been found to develop in response to the mutation of a single gene – the RB1 gene—demonstrating that some cells are only a step away from developing into a life-threatening malignancy.

David E. Cobrinik, MD, PhD, of The Vision Center at Children's ...