(Press-News.org) A new study published in the Cell Press journal Current Biology on October 2 could rewrite the story of ape and human brain evolution. While the neocortex of the brain has been called "the crowning achievement of evolution and the biological substrate of human mental prowess," newly reported evolutionary rate comparisons show that the cerebellum expanded up to six times faster than anticipated throughout the evolution of apes, including humans.

The findings suggest that technical intelligence was likely at least as important as social intelligence in human cognitive evolution, the researchers say.

"Our results highlight a previously unappreciated role of the cerebellum in ape and human brain evolution that has the potential to refocus researchers' thinking about how and why the brains in these species have become distinct and to shift attention away from an almost exclusive focus on the neocortex as the seat of our humanity," says Robert Barton of Durham University in the United Kingdom.

The cerebellum had been seen primarily as a brain region involved in movement control, adds Chris Venditti of the University of Reading. But more recent evidence has begun to suggest that the cerebellum has a broader range of functions. The cerebellum also contains an intriguingly large number of densely packed neurons.

"In humans, the cerebellum contains about 70 billion neurons—four times more than in the neocortex," Barton says. "Nobody really knows what all these neurons are for, but they must be doing something important."

The neocortex had gotten most of the attention in part because it is such a large structure to begin with. As a result, in looking at variation in the size of various brain regions, the neocortex appeared to show the most expansion. But much of that increase in size could be explained away by the size of the animal as a whole. Sperm whales have a neocortex that is proportionally larger than that of humans, for example.

By using a comparative method that controlled for those differences in the way the two brain structures correlate, Barton and Venditti uncovered a striking pattern: both nonhuman apes and humans depart from the otherwise tight correlation in size between the cerebellum and neocortex found across other primates due to relatively rapid evolutionary expansion of the cerebellum.

Barton and Venditti say that the cerebellum seems to be particularly involved in the temporal organization of complex behavioral sequences, such as those involved in making and using tools, for instance. Interestingly, evidence is now emerging for a critical role of the cerebellum in language, too.

While plenty of work remains, the new study establishes the cerebellum as "a new frontier for investigations into the neural basis of advanced cognitive abilities," the researchers say.

INFORMATION:

Current Biology Barton et al.: "Rapid evolution of the cerebellum in humans and other great apes."

Unexpectedly speedy expansion of human, ape cerebellum

2014-10-02

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

How curiosity changes the brain to enhance learning

2014-10-02

The more curious we are about a topic, the easier it is to learn information about that topic. New research publishing online October 2 in the Cell Press journal Neuron provides insights into what happens in our brains when curiosity is piqued. The findings could help scientists find ways to enhance overall learning and memory in both healthy individuals and those with neurological conditions.

"Our findings potentially have far-reaching implications for the public because they reveal insights into how a form of intrinsic motivation—curiosity—affects memory. These findings ...

Stopping liver cancer in its tracks

2014-10-02

This release is available in Japanese.

A University of Tokyo research group has discovered that AIM (Apoptosis Inhibitor of Macrophage), a protein that plays a preventive role in obesity progression, can also prevent tumor development in mice liver cells. This discovery may lead to a therapy for hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC), the most common type of liver cancer and the third most common cause of cancer deaths.

Professor Toru Miyazaki's group at the Laboratory of Molecular Biomedicine from Pathogenesis, in the Faculty of Medicine has shown that AIM (also known ...

Ancient protein-making enzyme moonlights as DNA protector

2014-10-02

LA JOLLA, CA—October 2, 2014—Scientists at The Scripps Research Institute (TSRI) have found that an enzyme best known for its fundamental role in building proteins has a second major function: to protect DNA during times of cellular stress.

The finding is remarkable on a basic science level but also points the way to possible therapeutic applications. Strategies that enhance the DNA-protection function of the enzyme, TyrRS, could help protect people from radiation injuries as well as from hereditary defects in DNA repair systems.

"We overexpressed TyrRS in zebrafish ...

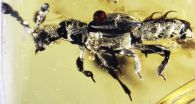

52-million-year-old amber preserves 'ant-loving' beetle

2014-10-02

Scientists have uncovered the fossil of a 52-million-year old beetle that likely was able to live alongside ants—preying on their eggs and usurping resources—within the comfort of their nest. The fossil, encased in a piece of amber from India, is the oldest-known example of this kind of social parasitism, known as "myrmecophily." Published today in the journal Current Biology, the research also shows that the diversification of these stealth beetles, which infiltrate ant nests around the world today, correlates with the ecological rise of modern ants.

"Although ants ...

Counting the seconds for immunological tolerance

2014-10-02

Our immune system must distinguish between self and foreign and in order to fight infections without damaging the body's own cells at the same time. The immune system is loyal to cells in the body, but how this works is not fully understood. Researchers in the Departments of Biomedicine and Nephrology at the University Hospital and the University of Basel have discovered that the immune system uses a molecular biological clock to target intolerant T cells during their maturation process. These recent findings have been reported in the scientific journal Cell.

A functioning ...

DNA 'bias' may keep some diseases in circulation, Penn biologists show

2014-10-02

It's an early lesson in genetics: we get half our DNA from Mom, half from Dad.

But that straightforward explanation does not account for a process that sometimes occurs when cells divide. Called gene conversion, the copy of a gene from Mom can replace the one from Dad, or vice versa, making the two copies identical.

In a new study published in the American Journal of Human Genetics, University of Pennsylvania researchers Joseph Lachance and Sarah A. Tishkoff investigated this process in the context of the evolution of human populations. They found that a bias toward ...

Study indicates possible new way to treat endometrial, colon cancers

2014-10-02

Scientists love acronyms.

In the quest to solve cancer's mysteries, they come in handy when describing tongue-twisting processes and pathways that somehow allow tumors to form and thrive. Two examples are ERK (extracellular-signal-related kinase) and JNK (c-June N-Terminal Kinase), enzymes that may offer unexpected solutions for treating some endometrial and colon cancers.

A study led by Gordon Mills, M.D., Ph.D., professor and chair of Systems Biology at The University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center with Lydia Cheung, Ph.D. as the first author, points to cellular ...

Study gauges humor by age

2014-10-02

Television sitcoms in which characters make jokes at someone else's expense are no laughing matter for older adults, according to a University of Akron researcher.

Jennifer Tehan Stanley, an assistant professor of psychology, studied how young, middle-aged and older adults reacted to so-called "aggressive humor"—the kind that is a staple on shows like The Office.

By showing clips from The Office and other sitcoms (Golden Girls, Mr. Bean, Curb Your Enthusiasm) to adults of varying ages, she and colleagues at two other universities found that young and middle-aged adults ...

Strong working memory puts brakes on problematic drug use

2014-10-02

AUDIO:

Atika Khurana, assistant professor in the University of Oregon's Department of Counseling Psychology and Human Services, provides a short summary and the implications of a study that looked at the...

Click here for more information.

EUGENE, Ore. -- Oct. 2, 2014 -- Adolescents with strong working memory are better equipped to escape early drug experimentation without progressing into substance abuse issues, says a University of Oregon researcher.

Most important in the picture ...

Sense of invalidation uniquely risky for troubled teens

2014-10-02

PROVIDENCE, R.I. [Brown University] — Among the negative feelings that can plague a teen's psyche is a perception of "invalidation," or a lack of acceptance. A new study by Brown University and Butler Hospital researchers suggests that independent of other known risk factors, measuring teens' sense of invalidation by family members or peers can help predict whether they will try to harm themselves or even attempt suicide.

In some cases, as with peers, that sense of invalidation could come from being bullied, but it could also be more subtle. In the case of family, for ...