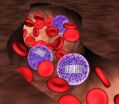

(Press-News.org) Researchers at University of California, San Diego School of Medicine have discovered that T-cells – a type of white blood cell that learns to recognize and attack microbial pathogens – are activated by a pain receptor.

The study, reported online Oct. 5 in Nature Immunology, shows that the receptor helps regulate intestinal inflammation in mice and that its activity can be manipulated, offering a potential new target for treating certain autoimmune disorders, such as Crohn's disease and possibly multiple sclerosis.

"We have a new way to regulate T-cell activation and potentially better control immune-mediated diseases," said senior author Eyal Raz, MD, professor of medicine.

The receptor, called a TRPV1 channel, has a well-recognized role on nerve cells that help regulate body temperature and alert the brain to heat and pain. It is also sometimes called the capsaicin receptor because of its role in producing the sensation of heat from chili peppers.

The study is the first to show that these channels are also present on T-cells, where they are involved in gating the influx of calcium ions into cells – a process that is required for T-cell activation.

"Our study breaks current dogma in which certain ion channels called CRAC are the only players involved in calcium entry required for T-cell function," said lead author Samuel Bertin, a postdoctoral researcher in the Raz laboratory. "Understanding the physical structures that enable calcium influx is critical to understanding the body's immune response."

T-cells are targeted by the HIV virus and their destruction is why people with AIDS have compromised immune function. Certain vaccines also exploit T-cells by harnessing their ability to recognize antigens and trigger the production of antibodies, conferring disease resistance. Allergies, in contrast, may occur when T-cells recognize harmless substances as pathogenic.

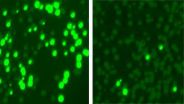

TRPV1 channels appear to offer a way to manipulate T-cell response as needed for health. Specifically, in in vitro experiments researchers showed that T-cell inflammatory response could be reduced by knocking down the gene that encodes for the protein that comprises the TRPV1 channel. Overexpression of this gene was shown to lead to a surge in T-cell activation, which in human health may contribute to autoimmune diseases. T-cells also responded to pharmaceutical agents that block or activate the TRPV1 channel.

In experiments with mice models, researchers were able to reduce colitis with a TRPV1-blocker, initially developed as a new painkiller. One of the promising discoveries is that colitis in mice could be treated with much lower doses than what is needed to dull pain. "This suggests we could potentially treat some autoimmune diseases with doses that would not affect people's protective pain response," Raz said.

INFORMATION:

Co-authors include Petrus Rudolf de Jong, Jihyung Lee, Keith To, Lior Abramson, Timothy Yu, Tiffany Han, Ranim Touma, Xiangli Li, José M. González-Navajas, Scott Herdman, Maripat Corr, Hui Dong, and Alessandra Franco, UC San Diego; Yukari Aoki-Nonaka, UC San Diego and Niigata University Graduate School of Medical and Dental Sciences, Japan; Lilian L. Nohara, Hongjian Xu, Shawna R. Stanwood and Wilfred A. Jefferies, University of British Columbia; Sonal Srikanth and Yousang Gwack, UCLA; and Guo Fu, The Scripps Research Institute.

This study was funded, in part, by National Institutes of Health (U01 AI095623, P01 DK35108 and P30 NS047101), The Broad Foundation, Crohn's and Colitis Foundation of America, Canadian Institutes of Health Research, Fulbright Association, Philippe Foundation Inc. and Japan Society for the Promotion of Science.

Experiments in mice with a bone disorder similar to that in women after menopause show that a scientifically overlooked group of cells are likely crucial to the process of bone loss caused by the disorder, according to Johns Hopkins researchers. Their discovery, they say, not only raises the research profile of the cells, called preosteoclasts, but also explains the success and activity of an experimental osteoporosis drug with promising results in phase III clinical trials.

A summary of their work will be published on Oct. 5 in the journal Nature Medicine.

"We didn't ...

The largest genome-wide association study (GWAS) to date, involving more than 300 institutions and more than 250,000 subjects, roughly doubles the number of known gene regions influencing height to more than 400. The study, from the international Genetic Investigation of Anthropometric Traits (GIANT) Consortium, provides a better glimpse at the biology of height and offers a model for investigating traits and diseases caused by many common gene changes acting together. Findings were published online October 5 by Nature Genetics.

"Height is almost completely determined ...

A 7-year-project to develop a barcoding and tracking system for tissue stem cells has revealed previously unrecognized features of normal blood production: New data from Harvard Stem Cell Institute scientists at Boston Children's Hospital suggests, surprisingly, that the billions of blood cells that we produce each day are made not by blood stem cells, but rather their less pluripotent descendants, called progenitor cells. The researchers hypothesize that blood comes from stable populations of different long-lived progenitor cells that are responsible for giving rise to ...

This news release is available in French and German. Physicians and researchers at CHU Sainte-Justine, Université de Montréal, CHU de Québec, Université Laval, and Hubrecht Institute have discovered a rare disease affecting both heart rate and intestinal movements. The disease, which has been named "Chronic Atrial Intestinal Dysrhythmia syndrome" (CAID), is a serious condition caused by a rare genetic mutation. This finding demonstrates that heart and guts rhythmic contractions are closely linked by a single gene in the human body, as shown in a study published on October ...

A new crystallographic technique developed at the University of Leeds is set to transform scientists' ability to observe how molecules work.

A research paper, published in the journal Nature Methods on October 5, describes a new way of doing time-resolved crystallography, a method that researchers use to observe changes within the structure of molecules.

Although fast time-resolved crystallography (Laue crystallography) has previously been possible, it has required advanced instrumentation that is only available at three sites worldwide. Only a handful of proteins ...

A study published in Nature Geoscience shows that air pollution has had a significant impact on the amount of water flowing through many rivers in the northern hemisphere.

The paper shows how such pollution, known as aerosols, can have an impact on the natural environment and highlights the importance of considering these factors in assessments of future climate change.

The research resulted from a collaboration between scientists at the Met Office, Centre for Ecology and Hydrology, University of Reading, Laboratoire de Météorologie Dynamique in France, and the University ...

The multitude of microbes scientists have found populating the human body have good, bad and mostly mysterious implications for our health. But when something goes wrong, we defend ourselves with the undiscriminating brute force of traditional antibiotics, which wipe out everything at once, regardless of the consequences.

Researchers at Rockefeller University and their collaborators are working on a smarter antibiotic. And in research to be published October 5 in Nature Biotechnology, the team describes a 'programmable' antibiotic technique that selectively targets the ...

Type 2 diabetes affects an estimated 28 million Americans according to the American Diabetes Association, but medications now available only treat symptoms, not the root cause of the disease. New research from Rutgers shows promising evidence that a modified form of a different drug, niclosamide – now used to eliminate intestinal parasites – may hold the key to battling the disease at its source.

The study, led by Victor Shengkan Jin, an associate professor of pharmacology at Rutgers Robert Wood Johnson Medical School, has been published online by the journal Nature ...

Montréal, October 2, 2014 – Scientists at the IRCM discovered a mechanism that promotes the progression of medulloblastoma, the most common brain tumour found in children. The team, led by Frédéric Charron, PhD, found that a protein known as Sonic Hedgehog induces DNA damage, which causes the cancer to develop. This important breakthrough will be published in the October 13 issue of the prestigious scientific journal Developmental Cell. The editors also selected the article to be featured on the journal's cover.

Sonic Hedgehog belongs to a family of proteins that gives ...

Despite the legalization of same-sex marriage in 19 states and the District of Columbia and an executive order to prohibit federal contractors from discrimination against lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender employees, LGBT individuals face tremendous hurdles in access to health care and basic human rights. A special report published by The Hastings Center, LGBT Bioethics: Visibility, Disparities, and Dialogue, is a call to action for the bioethics field to help right the wrongs in the ways that law, medicine, and society have treated LGBT people.

The editors are Tia ...