(Press-News.org) PHILADELPHIA — Nearly 60,000 Americans suffer from myasthenia gravis (MG), a non-inherited autoimmune form of muscle weakness. The disease has no cure, and the primary treatments are nonspecific immunosuppressants and inhibitors of the enzyme cholinesterase.

Now, a pair of researchers from the Perelman School of Medicine at the University of Pennsylvania have developed a fast-acting "vaccine" that can reverse the course of the disease in rats, and, they hope, in humans. Jon Lindstrom, PhD, a Trustee Professor in the department of Neuroscience led the study, published in the most recent issue of the Journal of Immunology, with senior research investigator Jie Luo, PhD.

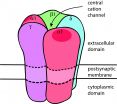

MG is caused by an autoimmune response to the acetylcholine receptor (AChR), a muscle protein that translates nervous system signals into muscle contractions. Autoantibodies target the part of these receptors found on the outer cell surface of muscle, leading to weakness.

Researchers can induce MG in rats by injecting the AChR protein, which produces an animal disease model called experimental autoimmune myasthenia gravis (EAMG). In this study, Lindstrom and Luo found that injecting rats with the part of the AChR found on the inside of the cell protects those animals from EAMG and reverses the course of the disease if administered after the EAMG has already been induced.

"We have an antigen-specific immunosuppressive therapy that works on the animal model and should work on human MG," says Lindstrom, adding that such therapies are "rarer than hens' teeth."

A vaccine dose of 1 mg per week for six weeks, the team found, was sufficient to block development of chronic EAMG in rats. But significantly, the vaccine also worked after induction of chronic EAMG, and could block re-induction of disease months later, as well. The vaccine appears to work by preventing synthesis of pathological antibodies to the extracellular surface of the AChR protein.

Although called a "vaccine," Lindstrom's therapeutic is not like a vaccine for influenza or measles. In those cases, the idea is to raise immunity to disease antigens that can then attack the pathogen should it infect the body in the future. In the case of MG, the vaccine targets immune cells that recognize and target a self protein – the acetylcholine receptor, which helps transmit neural signals from cell to cell – and marks them for death.

"We are trying to modulate a deviant immune response," Lindstrom explains.

The trick here is that the vaccine is made not from the portion of the AChR protein that the immune system normally would see – that part that is exposed on the outer surface of cells. Instead, it is built using the protein's cytoplasmic, or inner, cell regions. This formulation induces a robust, antigen-specific suppression of the immune response without also inducing MG itself. This may involve inhibition of cells involved in making pathological antibodies and regulating that response, but the exact mechanisms have not yet been determined.

Lindstrom's lab first described the vaccine itself in a 2010 publication in the Annals of Neurology. But this earlier work didn't try to block or treat chronic disease, and injected the vaccine without the use of a chemical cocktail that amplifies the resulting immune response, called an adjuvant. The present study suggests that pairing the vaccine with an adjuvant is safe – that is, it doesn't cause MG – and effective.

Now, says Lindstrom, the goal is to test this approach in animals with EAMG and MG using other human adjuvants and then move to human clinical trials.

INFORMATION:

The research was funded by the Muscular Dystrophy Association.

Penn Medicine is one of the world's leading academic medical centers, dedicated to the related missions of medical education, biomedical research, and excellence in patient care. Penn Medicine consists of the Raymond and Ruth Perelman School of Medicine at the University of Pennsylvania (founded in 1765 as the nation's first medical school) and the University of Pennsylvania Health System, which together form a $4.3 billion enterprise.

The Perelman School of Medicine has been ranked among the top five medical schools in the United States for the past 17 years, according to U.S. News & World Report's survey of research-oriented medical schools. The School is consistently among the nation's top recipients of funding from the National Institutes of Health, with $392 million awarded in the 2013 fiscal year.

The University of Pennsylvania Health System's patient care facilities include: The Hospital of the University of Pennsylvania -- recognized as one of the nation's top "Honor Roll" hospitals by U.S. News & World Report; Penn Presbyterian Medical Center; Chester County Hospital; Penn Wissahickon Hospice; and Pennsylvania Hospital -- the nation's first hospital, founded in 1751. Additional affiliated inpatient care facilities and services throughout the Philadelphia region include Chestnut Hill Hospital and Good Shepherd Penn Partners, a partnership between Good Shepherd Rehabilitation Network and Penn Medicine.

Penn Medicine is committed to improving lives and health through a variety of community-based programs and activities. In fiscal year 2013, Penn Medicine provided $814 million to benefit our community.

A new review of the way health care professionals emphasise weight to define health and wellbeing suggests the approach could be harmful to patients.

Author of the review article, Dr Rachel Calogero of the School of Psychology at the University of Kent, together with experts from other institutions and organisations, recommends that this approach, known as 'weight-normative', is replaced by health care professionals, public health officials and policy-makers with a 'weight-inclusive' approach.

Weight-inclusive approaches, such as the Health At Every Size initiative, ...

Hamilton, ON (October 7, 2014) – Hospital visitors and staff are greeted with hand sanitizer dispensers in the lobby, by the elevators and outside rooms as reminders to wash their hands to stop infections, but just how clean are patients' hands?

A study led by McMaster University researcher Dr. Jocelyn Srigley has found that hospitalized patients wash their hands infrequently. They wash about 30 per cent of the time while in the washroom, 40 per cent during meal times, and only three per cent of the time when using the kitchens on their units. Hand hygiene rates ...

LONDON, ON – New research shows probiotic yogurt can reduce the uptake of certain heavy metals and environmental toxins by up to 78% in pregnant women. Led by Scientists at Lawson Health Research Institute's Canadian Centre for Human Microbiome and Probiotic Research, this study provides the first clinical evidence that a probiotic yogurt can be used to reduce the deadly health risks associated with mercury and arsenic.

Environmental toxins like mercury and arsenic are commonly found in drinking water and food products, especially fish. These contaminants are particularly ...

Two years ago, Prof. Eshel Ben-Jacob of Tel Aviv University's School of Physics and Astronomy and Rice University's Center for Theoretical Biological Physics made the startling discovery that cancer, like an enemy hacker in cyberspace, targets the body's communication network to inflict widespread damage on the entire system. Cancer, he found, possessed special traits for cooperative behavior and used intricate communication to distribute tasks, share resources, and make decisions.

In research published in the Early Edition of the Proceedings of the National Academy of ...

NOAA's GOES-West satellite took a picture of Tropical Storm Simon weakening over Mexico's Baja California.

On Oct. 7, a Tropical Storm Watch was in effect for Punta Abreojos to Punta Eugenia, Mexico. The National Hurricane Center expects Simon to produce storm total rainfall amounts of 3 to 5 inches with isolated amounts around 8 inches through Wednesday, Oct. 8, across northern portions of the Baja California Peninsula and the state of Sonora in northwestern Mexico. Over the next few days, storm total rainfall amounts of 1 to 2 inches with isolated amounts of around ...

Eating disorders (ED) such as anorexia nervosa, bulimia, and binge eating disorder affect approximately 5-10% of the general population, but the biological mechanisms involved are unknown. Researchers at Inserm Unit 1073, "Nutrition, inflammation and dysfunction of the gut-brain axis" (Inserm/University of Rouen) have demonstrated the involvement of a protein produced by some intestinal bacteria that may be the source of these disorders. Antibodies produced by the body against this protein also react with the main satiety hormone, which is similar in structure. According ...

A new study led by Professor Kui Liu at the University of Gothenburg has identified the key molecule 'Greatwall kinase' which protects women's eggs against problems that can arise during the maturation process.

In order to be able to have a child, a woman needs eggs that can grow and mature. One of these eggs is then fertilised by a sperm, forming an embryo. During the maturation process, the egg needs to go through a number of stages of reductional division, called meiosis. If problems occur during any of these stages, the woman can become infertile. Around 10-15% of ...

The Gulf Sand gecko is a remarkable desert reptile in that it is the only lizard found habitually on sabkha substrate across large parts of the eastern Arabian Peninsula. These arid salt flats constitute one of the harshest habitats on earth, due to their extraordinary salinity.

The Gulf gecko, Pseudoceramodactylus khobarensis, belongs to a genus with a single species, and it is well adapted to this substrate featuring spiny scales beneath the fingers, long extremities and swollen nostrils.

Data on its distribution range showed a conspicuous gap between eastern United ...

October 7, 2014 – For women undergoing breast reconstruction using the advanced "DIEP" technique, a simple formula can reliably tell whether there will be sufficient blood flow to nourish the DIEP flap, reports a paper in Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery—Global Open®, the official open-access medical journal of the American Society of Plastic Surgeons (ASPS).

Drs Joseph Richard Dusseldorp and David G. Pennington of Macquarie University Hospital, Sydney, performed an ultrasound study to see how well the flap viability index (FVI) equation predicted blood ...

DETROIT – The only drug currently approved for treatment of stroke's crippling effects shows promise, when administered as a nasal spray, to help heal similar damage in less severe forms of traumatic brain injury.

In the first examination of its kind, researchers Ye Xiong, Ph.D, Zhongwu Liu, Ph.D., and Michael Chopp, Ph.D., Scientific Director of the Henry Ford Neuroscience Institute, found in animal studies that the brain's limited ability to repair itself after trauma can be enhanced when treated with the drug tPA, or tissue plasminogen activator.

"Using this ...