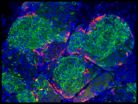

From human embryonic stem cells to billions of human insulin producing cells

Giant step toward new diabetes treatment

2014-10-09

(Press-News.org) Harvard stem cell researchers today announced that they have made a giant leap forward in the quest to find a truly effective treatment for type 1 diabetes, a condition that affects an estimated three million Americans at a cost of about $15 billion annually:

With human embryonic stem cells as a starting point, the scientists are for the first time able to produce, in the kind of massive quantities needed for cell transplantation and pharmaceutical purposes, human insulin-producing beta cells equivalent in most every way to normally functioning beta cells.

Doug Melton, who led the work and who twenty-three years ago, when his then infant son Sam was diagnosed with type 1 diabetes, dedicated his career to finding a cure for the disease, said he hopes to have human transplantation trials using the cells to be underway within a few years.

"We are now just one pre-clinical step away from the finish line," said Melton, whose daughter Emma also has type 1 diabetes.

A report on the new work has today been published by the journal Cell.

Felicia W. Pagliuca, Jeff Millman, and Mads Gurtler of Melton's lab are co-first authors on the Cell paper. The research group and paper authors include a Harvard undergraduate.

"You never know for sure that something like this is going to work until you've tested it numerous ways," said Melton, Harvard's Xander University Professor and a Howard Hughes Medical Institute Investigator. "We've given these cells three separate challenges with glucose in mice and they've responded appropriately; that was really exciting.

"It was gratifying to know that we could do something that we always thought was possible," he continued, "but many people felt it wouldn't work. If we had shown this was not possible, then I would have had to give up on this whole approach. Now I'm really energized."

The stem cell-derived beta cells are presently undergoing trials in animal models, including non-human primates, Melton said.

Elaine Fuchs, the Rebecca C. Lancefield Professor at Rockefeller University, and a Howard Hughes Medical Institute Investigator who is not involved in the work, hailed it as "one of the most important advances to date in the stem cell field, and I join the many people throughout the world in applauding my colleague for this remarkable achievement.

"For decades, researchers have tried to generate human pancreatic beta cells that could be cultured and passaged long term under conditions where they produce insulin. Melton and his colleagues have now overcome this hurdle and opened the door for drug discovery and transplantation therapy in diabetes," Fuchs said.

And Jose Oberholtzer, M.D., Associate Professor of Surgery, Endocrinology and Diabetes, and Bioengineering at the University of Illinois at Chicago, and its Director of the Islet and Pancreas Transplant Program and the Chief of the Division of Transplantation, said work described in today's Cell "will leave a dent in the history of diabetes. Doug Melton has put in a life-time of hard work in finding a way of generating human islet cells in vitro. He made it. This is a phenomenal accomplishment."

Melton, co-scientific director of the Harvard Stem Cell Institute, and the University's Department of Stem Cell and Regenerative Biology – both of which were created more than a decade after he began his quest – said that when he told his son and daughter they were surprisingly calm. "I think like all kids, they always assumed that if I said I'd do this, I'd do it," he said with a self-deprecating grin.

Type 1 diabetes is an autoimmune metabolic condition in which the body kills off all the pancreatic beta cells that produce the insulin needed for glucose regulation in the body. Thus the final pre-clinical step in the development of a treatment involves protecting from immune system attack the approximately 150 million cells that would have to be transplanted into each patient being treated. Melton is collaborating on the development of an implantation device to protect the cells with Daniel G. Anderson, the Samuel A. Goldblith Professor of Applied Biology, Associate Professor in the Department of Chemical Engineering, the Institute of Medical Engineering and Science, and the Koch Institute at MIT.

Melton said that the device Anderson and his colleagues at MIT are currently testing has thus far protected beta cells implanted in mice from immune attack for many months. "They are still producing insulin," Melton said.

Cell transplantation as a treatment for diabetes is still essentially experimental, uses cells from cadavers, requires the use of powerful immunosuppressive drugs, and has been available to only a very small number of patients.

MIT's Anderson said the new work by Melton's lab is "an incredibly important advance for diabetes. There is no question that ability to generate glucose-responsive, human beta cells through controlled differentiation of stem cells will accelerate the development of new therapeutics. In particular, this advance opens to doors to an essentially limitless supply of tissue for diabetic patients awaiting cell therapy."

Richard A. Insel, M.D., chief scientific officer of the Juvenile Diabetes Research Foundation, a funder of Melton's work, said the "JDRF is thrilled with this advancement toward large scale production of mature, functional human beta cells by Dr. Melton and his team. This significant accomplishment has the potential to serve as a cell source for islet replacement in people with type 1 diabetes and may provide a resource for discovery of beta cell therapies that promote survival or regeneration of beta cells and development of screening biomarkers to monitor beta cell health and survival to guide therapeutic strategies for all stages of the disease."

Melton expressed gratitude to both the Juvenile Diabetes Research Foundation and the Helmsley Trust, saying "their support has been, and continues to be essential."

While diabetics can keep their glucose metabolism under general control by injecting insulin multiple times a day, that does not provide the kind of exquisite fine tuning necessary to properly control metabolism, and that lack of control leads to devastating complications from blindness to loss of limbs.

About 10 percent of the more than 26 million Americans living with type 2 diabetes are also dependent upon insulin injections, and would presumably be candidates for beta cell transplants, Melton said.

"There have been previous reports of other labs deriving beta cell types from stem cells, no other group has produced mature beta cells as suitable for use in patients," he said. "The biggest hurdle has been to get to glucose sensing, insulin secreting beta cells, and that's what our group has done."

INFORMATION:In addition to the institutions cited above, the work was funded by the Harvard Stem Cell Institute, the National Institutes of Health, the JPB Foundation, and Mike and Amy Barry.

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

Special chromosomal structures control key genes

2014-10-09

CAMBRIDGE, Mass. (October 9, 2014) – Within almost every human cell is a nucleus six microns in diameter—about one 300th of a human hair's width—that is filled with roughly three meters of DNA. As the instructions for all cell processes, the DNA must be accessible to the cell's transcription machinery yet be compressed tightly enough to fit inside the nucleus. Scientists have long theorized that the way DNA is packaged affects gene expression. Whitehead Institute researchers present the first evidence that DNA scaffolding is responsible for enhancing and ...

Researchers identify a new class of 'good' fats

2014-10-09

BOSTON – The surprising discovery of a previously unidentified class of lipid molecules that enhance insulin sensitivity and blood sugar control offers a promising new avenue for the prevention and treatment of type 2 diabetes.

The new findings, made by a team of scientists from Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center (BIDMC) and the Salk Institute, are described in the October 9 online issue of the journal Cell.

"We were blown away to discover this completely new class of molecules," says senior author Barbara Kahn, MD, Vice Chair of the Department of Medicine ...

Scientists reveal why beer tastes good to us and to flies

2014-10-09

Beer yeasts produce chemicals that mimic the aroma of fruits in order to attract flies that can transport the yeast cells to new niches, report scientists from VIB, KU Leuven and NERF in the reputed journal Cell Reports. Interestingly, these volatile compounds are also essential for the flavor of beverages such as beer and wine.

Kevin Verstrepen (VIB/KU Leuven): "The importance of yeast in beer brewing has long been underestimated. But recent research shows that the choice of a particular yeast strain or variety explains differences in taste between different beers and ...

Set of molecules found to link insulin resistance in the brain to diabetes

2014-10-09

A key mechanism behind diabetes may start in the brain, with early signs of the disease detectable through rising levels of molecules not previously linked to insulin signaling, according to a study led by researchers at the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai published today in the journal Cell Metabolism.

Past studies had found that levels of a key set of protein building blocks, branched-chain amino acids (BCAAs), are higher in obese and diabetic patient, and that this rise occurs many years before someone develops diabetes. Why and how BCAA breakdown may be ...

New computational approach finds gene that drives aggressive brain cancer

2014-10-09

NEW YORK, NY (October 9, 2014)—Using an innovative algorithm that analyzes gene regulatory and signaling networks, Columbia University Medical Center (CUMC) researchers have found that loss of a gene called KLHL9 is the driving force behind the most aggressive form of glioblastoma, the most common form of brain cancer. The CUMC team demonstrated in mice transplants that these tumors can be suppressed by reintroducing KLHL9 protein, offering a possible strategy for treating this lethal disease. The study was published today in the online issue of Cell.

The team used ...

Scientists discover a 'good' fat that fights diabetes

2014-10-09

VIDEO:

Salk researchers explain how a new class of lipids may be tied to diabetes.

Click here for more information.

LA JOLLA—Scientists at the Salk Institute and Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center (BIDMC) in Boston have discovered a new class of molecules—produced in human and mouse fat—that protects against diabetes.

The researchers found that giving this new fat, or lipid, to mice with the equivalent of type 2 diabetes lowered their elevated blood sugar, ...

Long-term treatment success using gene therapy to correct a lethal metabolic disorder

2014-10-09

New Rochelle, NY, October 9, 2014—Excessive and often lethal blood levels of bilirubin can result from mutations in a single gene that are the cause of the metabolic disease known as Crigler-Najjar syndrome type 1 (CNS1). A new gene therapy approach to correcting this metabolic error achieved significant, long-lasting reductions in bilirubin levels in a mouse model of CNS1 and is described in an Open Access article in Human Gene Therapy, a peer-reviewed journal from Mary Ann Liebert, Inc., publishers. The article is available on the Human Gene Therapy website at http://online.liebertpub.com/doi/full/10.1089/hum.2013.233. ...

Clove oil tested for weed control in organic Vidalia sweet onion

2014-10-09

TIFTON, GA – Weed control is one of the most challenging aspects of organic crop production. Most growers of certified organic crops rely heavily on proven cultural and mechanical weed control methods while limiting the use of approved herbicides. A new study of herbicides derived from clove oil tested the natural products' effectiveness in controlling weeds in Vidalia® sweet onion crops.

"Cultivation with a tine weeder and hand weeding are the primary tools currently used for weed control in organic sweet onion (Allium ceps)," explained scientist W. Carroll ...

Wild tomato species focus of antioxidant study

2014-10-09

IZMIR, TURKEY – Tomatoes are known to be rich in antioxidants such as vitamin C, lycopene, β-carotene, and phenolics. Antioxidants, substances capable of delaying or inhibiting oxidation processes caused by free radicals, are of interest to consumers for their health-related contributions, and to plant breeders for their ability to provide plants with natural resistance to biotic and abiotic stresses. While tomato domestication and breeding programs have typically focused on traits such as fruit weight, color, shape, and disease resistance, scientists are now ...

Study examines effect of antibiotic susceptibility for patients with bloodstream infection

2014-10-09

In an analysis of more than 8,000 episodes of Staphylococcus aureus bloodstream infections, there were no significant differences in the risk of death when comparing patients exhibiting less susceptibility to the antibiotic vancomycin to patients with more vancomycin susceptible strains of S. aureus, according to a study published in JAMA. The study is being released early online to coincide with the IDWeek 2014 meeting.

Staphylococcus aureus is among the most common causes of health care-associated infection throughout the world. It causes a wide range of infections, ...

LAST 30 PRESS RELEASES:

The RESIL-Card tool launches across Europe to strengthen cardiovascular care preparedness against crises

Tools to glimpse how “helicity” impacts matter and light

Smartphone app can help men last longer in bed

Longest recorded journey of a juvenile fisher to find new forest home

Indiana signs landmark education law to advance data science in schools

A new RNA therapy could help the heart repair itself

The dehumanization effect: New PSU research examines how abusive supervision impacts employee agency and burnout

New gel-based system allows bacteria to act as bioelectrical sensors

The power of photonics

From pioneer to leader: Alex Zhavoronkov chairs precision aging discussion and presents Luminary Award to OpenAI president at PMWC 2026

Bursting cancer-seeking microbubbles to deliver deadly drugs

In a South Carolina swamp, researchers uncover secrets of firefly synchrony

American Meteorological Society and partners issue statement on public availability of scientific evidence on climate change

How far will seniors go for a doctor visit? Often much farther than expected

Selfish sperm hijack genetic gatekeeper to kill healthy rivals

Excessive smartphone use associated with symptoms of eating disorder and body dissatisfaction in young people

‘Just-shoring’ puts justice at the center of critical minerals policy

A new method produces CAR-T cells to keep fighting disease longer

Scientists confirm existence of molecule long believed to occur in oxidation

The ghosts we see

ACC/AHA issue updated guideline for managing lipids, cholesterol

Targeting two flu proteins sharply reduces airborne spread

Heavy water expands energy potential of carbon nanotube yarns

AMS Science Preview: Mississippi River, ocean carbon storage, gender and floods

High-altitude survival gene may help reverse nerve damage

Spatially decoupling active-sites strategy proposed for efficient methanol synthesis from carbon dioxide

Recovery experiences of older adults and their caregivers after major elective noncardiac surgery

Geographic accessibility of deceased organ donor care units

How materials informatics aids photocatalyst design for hydrogen production

BSO recapitulates anti-obesity effects of sulfur amino acid restriction without bone loss

[Press-News.org] From human embryonic stem cells to billions of human insulin producing cellsGiant step toward new diabetes treatment