(Press-News.org) COLUMBUS, Ohio—Our view of other solar systems just got a little more familiar, with the discovery of a planet 25,000 light-years away that resembles our own Uranus.

Astronomers have discovered hundreds of planets around the Milky Way, including rocky planets similar to Earth and gas planets similar to Jupiter. But there is a third type of planet in our solar system—part gas, part ice—and this is the first time anyone has spotted a twin for our so-called "ice giant" planets, Uranus and Neptune.

An international research team led by Radek Poleski, postdoctoral researcher at The Ohio State University, described the discovery in a paper appearing online in The Astrophysical Journal.

While Uranus and Neptune are mostly composed of hydrogen and helium, they both contain significant amounts of methane ice, which gives them their bluish appearance. Given that the newly discovered planet is so far away, astronomers can't actually tell anything about its composition. But its distance from its star suggests that it's an ice giant—and since the planet's orbit resembles that of Uranus, the astronomers are considering it to be a Uranus analog.

Regardless, the newly discovered planet leads a turbulent existence: it orbits one star in a binary star system, with the other star close enough to disturb the planet's orbit.

The find may help solve a mystery about the origins of the ice giants in our solar system, said Andrew Gould, professor of astronomy at Ohio State.

"Nobody knows for sure why Uranus and Neptune are located on the outskirts of our solar system, when our models suggest that they should have formed closer to the sun," Gould said. "One idea is that they did form much closer, but were jostled around by Jupiter and Saturn and knocked farther out."

"Maybe the existence of this Uranus-like planet is connected to interference from the second star," he continued. "Maybe you need some kind of jostling to make planets like Uranus and Neptune."

The binary star system lies in our Milky Way galaxy, in the direction of Sagittarius. The first star is about two thirds as massive as our sun, and the second star is about one sixth as massive. The planet is four times as massive as Uranus, but it orbits the first star at almost exactly the same distance as Uranus orbits our sun.

The astronomers spotted the solar system due to a phenomenon called gravitational microlensing—when the gravity of a star focuses the light from a more distant star and magnifies it like a lens. Very rarely, the signature of a planet orbiting the lens star appears within that magnified light signal.

In this case, there were two separate microlensing events, one in 2008 that revealed the main star and suggested the presence of the planet, and one in 2010 that confirmed the presence of the planet and revealed the second star. Both observations were done with the 1.3-meter Warsaw Telescope at Las Campanas Observatory in Chile as part of the Optical Gravitational Lensing Experiment (OGLE).

Poleski led the analysis, which entailed combining the two OGLE observations. When he did, he was able to calculate the masses of the two stars and the planet, and their distances from one another—a feat that he says can only be done via microlensing.

"Only microlensing can detect these cold ice giants that, like Uranus and Neptune, are far away from their host stars. This discovery demonstrates that microlensing is capable of discovering planets in very wide orbits," Poleski said.

"We were lucky to see the signal from the planet, its host star, and the companion star. If the orientation had been different, we would have seen only the planet, and we probably would have called it a free-floating planet," he added.

The 2008 and 2010 events are part of the OGLE database, which contains 13,000 microlensing events that have been recorded since the project began. Part of Poleski's job at Ohio State entails writing software to mine the database for other possible connections that could lead to additional planet discoveries—including more ice giants.

INFORMATION:

Coauthors on the paper hailed from Warsaw University Observatory, Chungbuk National University, University of Cambridge, Peking University, Institute for Advanced Study, and Universidad de Concepción in Chile.

Funding for this work came from the European Research Council, The Thomas Jefferson Chair for Discovery and Space Exploration, the Polish Ministry of Science and Higher Education, the National Research Foundation of Korea, the Chinese Academy of Sciences and the National Science Foundation.

Contacts

Andrew Gould

614-292-1892

Gould.34@osu.edu

Radek Poleski

614-292-1892

Poleski.1@osu.edu

Written by Pam Frost Gorder

614-292-9475

Gorder.1@osu.edu

This news release is available in German. Public spending appears to have contributed substantially to the fact that life expectancy in eastern Germany has not only increased, but is now almost equivalent to life expectancy in the west. While the possible connection of public spending and life expectancy has been a matter of debate, scientists at the Max Planck Institute for Demographic Research (MPIDR) have now for the first time quantified the effect. They found that for each additional euro the eastern Germans received in benefits from pensions and public health ...

VIDEO:

Fruit fly border cells form clusters of six to eight cells, which display directional migration during oogenesis. Migration of border cells in egg chambers can be examined in detail by...

Click here for more information.

Cell migration is important for development and physiology of multicellular organisms. During embryonic development individual cells and cell clusters can move over relatively long distances, and cell migration is also essential for wound healing and many ...

Researchers from the University of Sheffield have found vital new evidence on how to target and reverse the effects caused by one of the most common genetic causes of Parkinson's.

Mutations in a gene called LRRK2 carry a well-established risk for Parkinson's disease, however the basis for this link is unclear.

The team, led by Parkinson's UK funded researchers Dr Kurt De Vos from the Department of Neuroscience and Dr Alex Whitworth from the Department of Biomedical Sciences, found that certain drugs could fully restore movement problems observed in fruit flies carrying ...

CORVALLIS, Ore. – Since the first undersea methane seep was discovered 30 years ago, scientists have meticulously analyzed and measured how microbes in the seafloor sediments consume the greenhouse gas methane as part of understanding how the Earth works.

The sediment-based microbes form an important methane "sink," preventing much of the chemical from reaching the atmosphere and contributing to greenhouse gas accumulation. As a byproduct of this process, the microbes create a type of rock known as authigenic carbonate, which while interesting to scientists was ...

Just 14 per cent of the population has an Advance Directive, or "living will", detailing their end of life treatment and care preferences, according to an article led by QUT Australian Centre for Health Law Research director Professor Ben White.

This research is from a joint University of Queensland, QUT and Victoria University study, supported by the Australian Research Council in partnership with seven public trustee organisations across Australia.

An Advance Directive is a legal document in which a person specifies what treatment or end of life care they want, when ...

ITHACA, N.Y. – Have you ever noticed you find your candidate for political office more attractive than the opponent? New research from Cornell University shows you're not the only one.

"We showed pictures of familiar and unfamiliar political leaders to voters in two different samples and found that familiarity and partisanship each significantly influenced how candidates were perceived," said the study's lead researcher, said Kevin M. Kniffin, a postdoctoral research associate at Cornell's Dyson School of Applied Economics and Management. "For example, Democrats ...

PULLMAN, Wash. – With global food demand expected to outpace the availability of water by the year 2050, consumers can make a big difference in reducing the water used in livestock production.

"It's important to know that small changes on the consumer side can help, and in fact may be necessary, to achieve big results in a production system," said Robin White, lead researcher of a Washington State University study appearing in the journal Food Policy.

WSU economist Mike Brady demonstrated that the willingness of consumers to pay a little more for meat products labeled ...

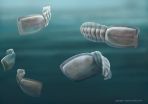

More than 100 years since they were first discovered, some of the world's most bizarre fossils have been identified as distant relatives of humans, thanks to the work of University of Adelaide researchers.

The fossils belong to 500-million-year-old blind water creatures, known to scientists as "vetulicolians" (pronounced: ve-TOO-lee-coal-ee-ans).

Alien-like in appearance, these marine creatures were "filter-feeders" shaped like a figure-of-8. Their strange anatomy has meant that no-one has been able to place them accurately on the tree of life, until now.

In a new ...

Philadelphia, PA, October 15, 2014 – Are deficits in attention limited to those with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) or is there a spectrum of attention function in the general population? The answer to this question has implications for psychiatric diagnoses and perhaps for society, broadly.

A new study published in the current issue of Biological Psychiatry, by researchers at Cardiff University School of Medicine and the University of Bristol, suggests that there is a spectrum of attention, hyperactivity/impulsiveness and language function in society, ...

Galaxy clusters are the largest objects in the Universe held together by gravity but their formation is not well understood. The Spiderweb Galaxy (formally known as MRC 1138-262 [1]) and its surroundings have been studied for twenty years, using ESO and other telescopes [2], and is thought to be one of the best examples of a protocluster in the process of assembly, more than ten billion years ago.

But Helmut Dannerbauer (University of Vienna, Austria) and his team strongly suspected that the story was far from complete. They wanted to probe the dark side of star formation ...