(Press-News.org) This news release is available in German.

Why do male animals need millions of sperms every day in order to reproduce? And why are there two sexes anyway? These and related questions are the topic of the latest issue of the research journal Molecular Human Reproduction published today (Oct. 16th, 2014). The evolutionary biologist Steven Ramm from Bielefeld University Bielefeld has compiled this special issue on sperm competition. In nature, it is not unusual for a female to copulate with several males in quick succession – chimpanzees are one good example. 'The sperm of the different males then compete within the female to fertilize the eggs,' says Ramm. 'Generally speaking, the best sperm wins. This may involve its speed or also be due to the amount of sperm transferred. It can also be useful for the seminal fluid to be viscous, meaning it sticks inside the female reproductive tract to try to keep other sperm at bay.'

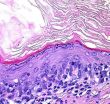

When the sperm of one male compete with those of another, the sperm cells they produce need to be well adapted to this 'fight over the egg'. 'Producing the optimum sperm type occurs in the testis, during spermatogenesis,' explains Ramm. This is the topic of his own article, written together with three colleagues from the Universities of Basel (Switzerland) and Münster. Sperm are considered to be the most diverse type of cell in the entire animal kingdom. The researchers describe how different sperm cells are formed in for example flies, roundworms, and vertebrates. They also show that it is not just the amount of sperm that is important, but also its form. 'Even just the size of the individual sperm cell may provide a competitive advantage,' says Ramm. Alongside human sperm that are tiny and swim with their tails, there are, for example, spherical and crawling sperm or even giant sperm that are larger than the male that produces them.

Evolutionary biologists study how living creatures have developed over millions of years. They focus on asking how they are adapted to their environment. 'The main concern in our special issue is to try to understand why reproduction in animals happens in the way that it does,' says Ramm. 'In the long term, this knowledge could, for example, help reproductive biologists to modify sperm genetically to increase the chance of fertilization. One possible application of such methods could be to help conserve endangered species.'

Dr. Steven Ramm has been engaged in research at Bielefeld University's Faculty of Biology since 2012. One of his research topics in the Department of Evolutionary Biology is to identify what characteristics of male animals enable them to successfully reproduce. In 2006, Ramm graduated with his doctorate from the University of Liverpool (England) where he carried on doing research until 2009. This was followed by research at the University of Innsbruck (Austria) and the University of Basel (Switzerland). Ramm is leading the project 'Functional and evolutionary genetics of seminal fluid', funded by the German Research Foundation (DFG). He is also responsible for the EU research project 'SpermEvolution'.

INFORMATION:

Original publication:

Steven A. Ramm, Sperm competition and the evolution of reproductive systems (Editorial). Molecular Human Reproduction, http://dx.doi.org/10.1093/molehr/gau076, published on 16 October 2014

Steven A. Ramm, Lukas Schärer, Jens Ehmcke, Joachim Wistuba, Sperm competition and the evolution of spermatogenesis. Molecular Human Reproduction, http://dx.doi.org/10.1093/molehr/gau070, published on 16 October 2014

Sperm wars

Evolutionary biologist at Bielefeld University compiles international special issue on sperm competition

2014-10-17

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

Presence of enzyme may worsen effects of spinal cord injury and impair long-term recovery

2014-10-17

Philadelphia, PA, October 16, 2014 – Traumatic spinal cord injury (SCI) is a devastating condition with few treatment options. Studies show that damage to the barrier separating blood from the spinal cord can contribute to the neurologic deficits that arise secondary to the initial trauma. Through a series of sophisticated experiments, researchers reporting in The American Journal of Pathology suggest that matrix metalloproteinase-3 (MMP-3) plays a pivotal role in disruption of the brain/spinal cord barrier (BSCB), cell death, and functional deficits after SCI. This ...

Scientists opens black box on bacterial growth in cystic fibrosis lung infection

2014-10-17

Researchers from the University of Copenhagen have shown for the first time how bacteria can grow directly in the lungs of Cystic fibrosis patients, giving them the opportunity to get tremendous insights into bacteria behavior and growth in chronic infections.

The study also discovered the bacterial growth in chronic lung infections among cystic fibrosis (CF) patients was halted or slowed down by the immune cells. The researchers discovered the immune cells consumed all the oxygen and helped "suffocate" the bacteria, forcing the bacteria to switch to a much slower growth.

The ...

High-speed evolution in the lab

2014-10-17

DNA analysis has become increasingly efficient and cost-effective since the human genome was first fully sequenced in the year 2001. Sequencing a complete genome, however, still costs around US$1,000. Sequencing the genetic code of hundreds of individuals would therefore be very expensive and time-consuming. In particular for non-human studies, researchers very quickly hit the limit of financial feasibility.

Sequencing Groups Instead of Individuals

The solution to this problem is pool sequencing (Pool-Seq). Schlötterer and his team sequence entire groups of fruit ...

Scientific breakthrough will help design the antibiotics of the future

2014-10-17

Scientists have used computer simulations to show how bacteria are able to destroy antibiotics – a breakthrough which will help develop drugs which can effectively tackle infections in the future.

Researchers at the University of Bristol focused on the role of enzymes in the bacteria, which split the structure of the antibiotic and stop it working, making the bacteria resistant.

The new findings, published in Chemical Communications, show that it's possible to test how enzymes react to certain antibiotics.

It's hoped this insight will help scientists to develop ...

Physicists warning to 'nail beauty fans' applies to animals too

2014-10-17

The daily trimming of fingernails and toenails to make them more aesthetically pleasing could be detrimental and potentially lead to serious nail conditions. The research, carried out by experts in the School of Veterinary Medicine and Science at The University of Nottingham, will also improve our understanding of disease in the hooves of farm animals and horses.

Dr Cyril Rauch, a physicist and applied mathematician, together with his PhD Student Mohammed Cherkaoui-Rbati, devised equations to identify the physical laws that govern nail growth, and used them to throw ...

Emergency aid for overdoses

2014-10-17

This news release is available in German. To date, antidotes exist for only a very few drugs. When treating overdoses, doctors are often limited to supportive therapy such as induced vomiting. Treatment is especially difficult if there is a combination of drugs involved. So what can be done if a child is playing and accidentally swallows his grandmother's pills? ETH professor Jean-Christophe Leroux from the Institute of Pharmaceutical Sciences at ETH Zurich wanted to find an answer to this question. "The task was to develop an agent that could eliminate many different ...

How the brain leads us to believe we have sharp vision

2014-10-17

Its central finding is that our nervous system uses past visual experiences to predict how blurred objects would look in sharp detail.

"In our study we are dealing with the question of why we believe that we see the world uniformly detailed," says Dr. Arvid Herwig from the Neuro-Cognitive Psychology research group of the Faculty of Psychology and Sports Science. The group is also affiliated to the Cluster of Excellence Cognitive Interaction Technology (CITEC) of Bielefeld University and is led by Professor Dr. Werner X. Schneider.

Only the fovea, the central area of ...

UCLA research could help improve bladder function among people with spinal cord injuries

2014-10-17

People who have suffered spinal cord injuries are often susceptible to bladder infections, and those infections can cause kidney damage and even death.

New UCLA research may go a long way toward solving the problem. A team of scientists studied 10 paralyzed rats that were trained daily for six weeks with epidural stimulation of the spinal cord and five rats that were untrained and did not receive the stimulation. They found that training and epidural stimulation enabled the rats to empty their bladders more fully and in a timelier manner.

The study was published in ...

First step: From human cells to tissue-engineered esophagus

2014-10-17

In a first step toward future human therapies, researchers at The Saban Research Institute of Children's Hospital Los Angeles have shown that esophageal tissue can be grown in vivo from both human and mouse cells. The study has been published online in the journal Tissue Engineering, Part A.

The tissue-engineered esophagus formed on a relatively simple biodegradable scaffold after the researchers transplanted mouse and human organ-specific stem/progenitor cells into a murine model, according to principal investigator Tracy C. Grikscheit, MD, of the Developmental Biology ...

High-fat meals could be more harmful to males than females, according to new obesity research

2014-10-17

LOS ANGELES (Oct. 16, 2014) – Male and female brains are not equal when it comes to the biological response to a high-fat diet. Cedars-Sinai Diabetes and Obesity Research Institute scientist Deborah Clegg, PhD, and a team of international investigators found that the brains of male laboratory mice exposed to the same high-fat diet as their female counterparts developed brain inflammation and heart disease that were not seen in the females.

"For the first time, we have identified remarkable differences in the sexes when it comes to how the body responds to high-fat ...

LAST 30 PRESS RELEASES:

Subglacial weathering may have slowed Earth's escape from snowball Earth

Simple test could transform time to endometriosis diagnosis

Why ‘being squeezed’ helps breast cancer cells to thrive

Mpox immune test validated during Rwandan outbreak

Scientists pinpoint protein shapes that track Alzheimer’s progression

Researchers achieve efficient bicarbonate-mediated integrated capture and electrolysis of carbon dioxide

Study reveals ancient needles and awls served many purposes

Key protein SYFO2 enables 'self-fertilization’ of leguminous plants

AI tool streamlines drug synthesis

Turning orchard waste into climate solutions: A simple method boosts biochar carbon storage

New ACP papers say health care must be more accessible and inclusive for patients and physicians with disabilities

Moisture powered materials could make cleaning CO₂ from air more efficient

Scientists identify the gatekeeper of retinal progenitor cell identity

American Indian and Alaska native peoples experience higher rates of fatal police violence in and around reservations

Research alert: Long-read genome sequencing uncovers new autism gene variants

Genetic mapping of Baltic Sea herring important for sustainable fishing

In the ocean’s marine ‘snow,’ a scientist seeks clues to future climate

Understanding how “marine snow” acts as a carbon sink

In search of the room temperature superconductor: international team formulates research agenda

Index provides flu risk for each state

Altered brain networks in newborns with congenital heart disease

Can people distinguish between AI-generated and human speech?

New robotic microfluidic platform brings ai to lipid nanoparticle design

COSMOS trial results show daily multivitamin use may slow biological aging

Immune cells play key role in regulating eye pressure linked to glaucoma

National policy to remedy harms of race-based kidney function estimation associated with increased transplants for Black patients

Study finds teens spend nearly one-third of the school day on smartphones, with frequent checking linked to poorer attention

Team simulates a living cell that grows and divides

Study illuminates the experiences of people needing to seek abortion care out of state

Digital media use and child health and development

[Press-News.org] Sperm warsEvolutionary biologist at Bielefeld University compiles international special issue on sperm competition