(Press-News.org) The daily trimming of fingernails and toenails to make them more aesthetically pleasing could be detrimental and potentially lead to serious nail conditions. The research, carried out by experts in the School of Veterinary Medicine and Science at The University of Nottingham, will also improve our understanding of disease in the hooves of farm animals and horses.

Dr Cyril Rauch, a physicist and applied mathematician, together with his PhD Student Mohammed Cherkaoui-Rbati, devised equations to identify the physical laws that govern nail growth, and used them to throw light on the causes of some of the most common nail problems, such as ingrown toe nails, spoon-shaped nails and pincer nails.

According to their research, 'Physics of nail conditions: Why do ingrown nails always happen in the big toes?' published today, 17 October 2014, in the journal Physical Biology, regular poor trimming can tip the fine balance of nails, causing residual stress to occur across the entire nail. This residual stress can promote a change in shape or curvature of the nail over time which, in turn, can lead to serious nail conditions.

Dr Rauch also said: "Similar equations can be determined for conditions of the hoof and claw and applied to farm animals such as sheep, cattle, or horses and ponies. At a time when securing food across the world is important, a better understanding of the physics of hoof/claw has never been so essential to maintain the health of livestock and to sustain agriculture and food production."

It Started with Ingrowing Toe Nails

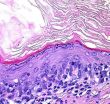

In their study the researchers focused specifically on ingrown toe nails which, though recognised for a long time, still lack a satisfactory treatment as the causes remain largely unknown. When devising their equations, the researchers accounted for the strong adhesion of nails to their bed through tiny, microscopic structures, which allow the nail to slide forwards and grow in a "ratchet-like" fashion by continuously binding and unbinding to the nail. By also taking into account the mechanical stresses and energies associated with the nail, the researchers came up with an overall nail shape equation.

The equation showed that when the balance between the growth stress and adhesive stress is broken — if a nail grows too quickly or slowly, or the number of adhesive structures changes — a residual stress across the entire nail can occur, causing it to change shape over time.

The results showed that residual stress can occur in any fingernail or toenail; however, the stress is greater for nails that are larger in size and have a flatter edge, which explains why ingrown toe nails predominantly occur in the big toe.

Although a residual stress can be brought about by age or a change in metabolic activity — ingrown toenails are often diagnosed in children/young adults and pregnant women — the equations also revealed that bad trimming of the nails can amplify the residual stress.

Physics Could Help Nail Down Stress

Dr Rauch said: "It is remarkable what some people are willing to do to make their nails look good, and it is in this context that I decided to look at what we really know about nails. Reading the scientific literature on nails I quickly realised that very little physics or maths had been applied to nails and their conditions.

"Looking at our results, we suggest that nail beauty fanatics who trim their nails on a daily basis opt for straight or parabolic edges, as otherwise they may amplify the imbalance of stresses which could lead to a number of serious conditions."

Rauch believes this research can be applied to farm animals and conditions associated with their hooves, which can be life threatening. He said: "I believe that physics can make a difference by promoting a new type of evidence-based veterinary medicine and help the veterinary and farrier communities by devising trimming methods to alleviate pain and potentially remove the cause of serious conditions."

INFORMATION:

A copy of the research paper is available on request.

This news release is available in German. To date, antidotes exist for only a very few drugs. When treating overdoses, doctors are often limited to supportive therapy such as induced vomiting. Treatment is especially difficult if there is a combination of drugs involved. So what can be done if a child is playing and accidentally swallows his grandmother's pills? ETH professor Jean-Christophe Leroux from the Institute of Pharmaceutical Sciences at ETH Zurich wanted to find an answer to this question. "The task was to develop an agent that could eliminate many different ...

Its central finding is that our nervous system uses past visual experiences to predict how blurred objects would look in sharp detail.

"In our study we are dealing with the question of why we believe that we see the world uniformly detailed," says Dr. Arvid Herwig from the Neuro-Cognitive Psychology research group of the Faculty of Psychology and Sports Science. The group is also affiliated to the Cluster of Excellence Cognitive Interaction Technology (CITEC) of Bielefeld University and is led by Professor Dr. Werner X. Schneider.

Only the fovea, the central area of ...

People who have suffered spinal cord injuries are often susceptible to bladder infections, and those infections can cause kidney damage and even death.

New UCLA research may go a long way toward solving the problem. A team of scientists studied 10 paralyzed rats that were trained daily for six weeks with epidural stimulation of the spinal cord and five rats that were untrained and did not receive the stimulation. They found that training and epidural stimulation enabled the rats to empty their bladders more fully and in a timelier manner.

The study was published in ...

In a first step toward future human therapies, researchers at The Saban Research Institute of Children's Hospital Los Angeles have shown that esophageal tissue can be grown in vivo from both human and mouse cells. The study has been published online in the journal Tissue Engineering, Part A.

The tissue-engineered esophagus formed on a relatively simple biodegradable scaffold after the researchers transplanted mouse and human organ-specific stem/progenitor cells into a murine model, according to principal investigator Tracy C. Grikscheit, MD, of the Developmental Biology ...

LOS ANGELES (Oct. 16, 2014) – Male and female brains are not equal when it comes to the biological response to a high-fat diet. Cedars-Sinai Diabetes and Obesity Research Institute scientist Deborah Clegg, PhD, and a team of international investigators found that the brains of male laboratory mice exposed to the same high-fat diet as their female counterparts developed brain inflammation and heart disease that were not seen in the females.

"For the first time, we have identified remarkable differences in the sexes when it comes to how the body responds to high-fat ...

New research into a rare pathogen has shown how a unique evolutionary trait allows it to infect even the healthiest of hosts through a smart solution to the body's immune response against it.

Scientists at the University of Birmingham have explained how a particular strain of a fungus, Cryptococcus gattii, responds to the human immune response and triggers a 'division of labour' in its invading cells, which can lead to life-threatening infections.

Once inhaled, the pathogen can spread through the body to cause pneumonia or meningitis. The outbreak strain of this fungus ...

(Vienna, October 17, 2014) Two new pill-only regimens that rapidly cure most patients with genotype 1 hepatitis C (HCV) infection could soon be widely prescribed across Europe. Two recently-published studies1,2 confirmed the efficacy and safety of combination therapy with two oral direct-acting antiviral agents (DAAs), with around 90% of patients cured after just 12-weeks of treatment.

At the 22nd United European Gastroenterology Week (UEG Week 2014) in Vienna, Austria, Professor Michael P. Manns from Hannover Medical School in Germany will be presenting this data and ...

A group of researchers led by Melina Bersten of the Kavli Institute for the Physics and Mathematics of the Universe recently presented a model that provides the first characterization of the progenitor for a hydrogen-deficient supernova. Their model predicts that a bright hot star, which is the binary companion to an exploding object, remains after the explosion. To verify their theory, the group secured observation time with the Hubble Space Telescope (HST) to search for such a remaining star. Their findings, which are reported in the October 2014 issue of The Astronomical ...

Peering through a giant cosmic magnifying glass, NASA's Hubble Space Telescope has spotted a tiny, faint galaxy -- one of the farthest galaxies ever seen. The diminutive object is estimated to be more than 13 billion light-years away.

This galaxy offers a peek back to the very early formative years of the universe and may just be the tip of the iceberg.

"This galaxy is an example of what is suspected to be an abundant, underlying population of extremely small, faint objects that existed about 500 million years after the big bang, the beginning of the universe," explained ...

NASA is carrying out its sixth consecutive year of Operation IceBridge research flights over Antarctica to study changes in the continent's ice sheet, glaciers and sea ice. This year's airborne campaign, which began its first flight Thursday morning, will revisit a section of the Antarctic ice sheet that recently was found to be in irreversible decline.

For the next several weeks, researchers will fly aboard NASA's DC-8 research aircraft out of Punta Arenas, Chile. This year also marks the return to western Antarctica following 2013's campaign based at the National Science ...