(Press-News.org) In a first step toward future human therapies, researchers at The Saban Research Institute of Children's Hospital Los Angeles have shown that esophageal tissue can be grown in vivo from both human and mouse cells. The study has been published online in the journal Tissue Engineering, Part A.

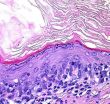

The tissue-engineered esophagus formed on a relatively simple biodegradable scaffold after the researchers transplanted mouse and human organ-specific stem/progenitor cells into a murine model, according to principal investigator Tracy C. Grikscheit, MD, of the Developmental Biology and Regenerative Medicine program of The Saban Research Institute and pediatric surgeon at Children's Hospital Los Angeles.

Progenitor cells have the ability to differentiate into specific types of cell, and can migrate to the tissue where they are needed. Their potential to differentiate depends on their type of "parent" stem cell and also on their niche. The tissue-engineering technique discovered by the CHLA researchers required only a simple polymer to deliver the cells, and multiple cellular groupings show the ability to generate a replacement organ with all cell layers and functions.

"We found that multiple combinations of cell populations allowed subsequent formation of engineered tissue. Different progenitor cells can find the right 'partner' cell in order to grow into specific esophageal cell types – such as epithelium, muscle or nerve cells – and without the need for exogenous growth factors. This means that successful tissue engineering of the esophagus is simpler than we previously thought," said Grikscheit.

She added that the study shows promise for one day applying the process in children who have been born with missing portions of the organ, which carries food, liquids and saliva from the mouth to the stomach. The process might also be used in patients who have had esophageal cancer – the fastest growing type of cancer in the U.S. – or otherwise damaged tissue, for example from accidentally swallowing caustic substances.

"We have demonstrated that a simple and versatile, biodegradable polymer is sufficient for the growth of tissue-engineered esophagus from human cells," added Grikscheit. "This not only serves as a potential source of tissue, but also a source of knowledge, as there are no other robust models available for studying esophageal stem cell dynamics. Understanding how these cells might behave in response to injury and how various donor cell types relate could expand the pool of potential donor cells for engineered tissue."

INFORMATION:

Additional contributors include first author Ryan G. Spurrier, MD, Allison L. Speer, MD, Xiaogang Hou, PhD and Wael N. El-Nachef, MD, of The Saban Research Institute of Children's Hospital Los Angeles. The study was supported by grants from the California Institute for Regenerative Medicine.

About Children's Hospital Los Angeles

Children's Hospital Los Angeles has been named the best children's hospital on the West Coast and among the top five in the nation for clinical excellence with its selection to the prestigious U.S. News & World Report Honor Roll. Children's Hospital is home to The Saban Research Institute, one of the largest and most productive pediatric research facilities in the United States. Children's Hospital is also one of America's premier teaching hospitals through its affiliation since 1932 with the Keck School of Medicine of the University of Southern California.

For more information, visit CHLA.org and follow us on ResearCHLAblog.org.

Media Contact: Debra Kain

dkain@chla.usc.edu

(323) 361-1812 or (323) 361-7628

First step: From human cells to tissue-engineered esophagus

2014-10-17

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

High-fat meals could be more harmful to males than females, according to new obesity research

2014-10-17

LOS ANGELES (Oct. 16, 2014) – Male and female brains are not equal when it comes to the biological response to a high-fat diet. Cedars-Sinai Diabetes and Obesity Research Institute scientist Deborah Clegg, PhD, and a team of international investigators found that the brains of male laboratory mice exposed to the same high-fat diet as their female counterparts developed brain inflammation and heart disease that were not seen in the females.

"For the first time, we have identified remarkable differences in the sexes when it comes to how the body responds to high-fat ...

Divide and conquer: Novel trick helps rare pathogen infect healthy people

2014-10-17

New research into a rare pathogen has shown how a unique evolutionary trait allows it to infect even the healthiest of hosts through a smart solution to the body's immune response against it.

Scientists at the University of Birmingham have explained how a particular strain of a fungus, Cryptococcus gattii, responds to the human immune response and triggers a 'division of labour' in its invading cells, which can lead to life-threatening infections.

Once inhaled, the pathogen can spread through the body to cause pneumonia or meningitis. The outbreak strain of this fungus ...

New pill-only regimens cure patients with hardest-to-treat hepatitis C infection

2014-10-17

(Vienna, October 17, 2014) Two new pill-only regimens that rapidly cure most patients with genotype 1 hepatitis C (HCV) infection could soon be widely prescribed across Europe. Two recently-published studies1,2 confirmed the efficacy and safety of combination therapy with two oral direct-acting antiviral agents (DAAs), with around 90% of patients cured after just 12-weeks of treatment.

At the 22nd United European Gastroenterology Week (UEG Week 2014) in Vienna, Austria, Professor Michael P. Manns from Hannover Medical School in Germany will be presenting this data and ...

Explosion first evidence of a hydrogen-deficient supernova progenitor

2014-10-17

A group of researchers led by Melina Bersten of the Kavli Institute for the Physics and Mathematics of the Universe recently presented a model that provides the first characterization of the progenitor for a hydrogen-deficient supernova. Their model predicts that a bright hot star, which is the binary companion to an exploding object, remains after the explosion. To verify their theory, the group secured observation time with the Hubble Space Telescope (HST) to search for such a remaining star. Their findings, which are reported in the October 2014 issue of The Astronomical ...

NASA's Hubble finds extremely distant galaxy through cosmic magnifying glass

2014-10-16

Peering through a giant cosmic magnifying glass, NASA's Hubble Space Telescope has spotted a tiny, faint galaxy -- one of the farthest galaxies ever seen. The diminutive object is estimated to be more than 13 billion light-years away.

This galaxy offers a peek back to the very early formative years of the universe and may just be the tip of the iceberg.

"This galaxy is an example of what is suspected to be an abundant, underlying population of extremely small, faint objects that existed about 500 million years after the big bang, the beginning of the universe," explained ...

NASA begins sixth year of airborne Antarctic ice change study

2014-10-16

NASA is carrying out its sixth consecutive year of Operation IceBridge research flights over Antarctica to study changes in the continent's ice sheet, glaciers and sea ice. This year's airborne campaign, which began its first flight Thursday morning, will revisit a section of the Antarctic ice sheet that recently was found to be in irreversible decline.

For the next several weeks, researchers will fly aboard NASA's DC-8 research aircraft out of Punta Arenas, Chile. This year also marks the return to western Antarctica following 2013's campaign based at the National Science ...

NASA spacecraft provides new information about sun's atmosphere

2014-10-16

NASA's Interface Region Imaging Spectrograph (IRIS) has provided scientists with five new findings into how the sun's atmosphere, or corona, is heated far hotter than its surface, what causes the sun's constant outflow of particles called the solar wind, and what mechanisms accelerate particles that power solar flares.

The new information will help researchers better understand how our nearest star transfers energy through its atmosphere and track the dynamic solar activity that can impact technological infrastructure in space and on Earth. Details of the findings appear ...

New Univeristy of Virginia study upends current theories of how mitochondria began

2014-10-16

Parasitic bacteria were the first cousins of the mitochondria that power cells in animals and plants – and first acted as energy parasites in those cells before becoming beneficial, according to a new University of Virginia study that used next-generation DNA sequencing technologies to decode the genomes of 18 bacteria that are close relatives of mitochondria.

The study appears this week in the online journal PLOS One, published by the Public Library of Science. It provides an alternative theory to two current theories of how simple bacterial cells were swallowed ...

Shrinking resource margins in Sahel region of Africa

2014-10-16

The need for food, animal feed and fuel in the Sahel belt is growing year on year, but supply is not increasing at the same rate. New figures from 22 countries indicate falling availability of resources per capita and a continued risk of famine in areas with low 'primary production' from plants. Rising temperatures present an alarming prospect, according to a study from Lund University in Sweden.

The research has investigated developments between the years 2000 and 2010 in the Sahel belt, south of the Sahara Desert. Over this ten-year period, the population of the region ...

How a molecular Superman protects the genome from damage

2014-10-16

Cold Spring Harbor, NY – How many times have we seen Superman swoop down from the heavens and rescue a would-be victim from a rapidly oncoming train?

It's a familiar scenario, played out hundreds of times in the movies. But the dramatic scene is reenacted in real life every time a cell divides. In order for division to occur, our genetic material must be faithfully replicated by a highly complicated machine, whose parts are tiny enough to navigate among the strands of the double helix.

The problem is that our DNA is constantly in use, with other molecular machines ...