(Press-News.org) Researchers with UCLA's Jonsson Comprehensive Cancer Center have found that melanoma patients whose cancers are caused by mutation of the BRAF gene become resistant to a promising targeted treatment through another genetic mutation or the overexpression of a cell surface protein, both driving survival of the cancer and accounting for relapse.

The study, published Nov. 24, 2010, in the early online edition of the peer-reviewed journal Nature, could result in the development of new targeted therapies to fight resistance once the patient stops responding and the cancer begins to grow again, said Dr. Roger Lo, senior author of the study.

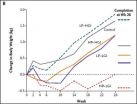

In a clinical trial at UCLA's Jonsson Cancer Center and other locations, patients with BRAF-mutated metastatic melanoma have been responding very well to an experimental drug, PLX4032. However, the responses are short lived, averaging seven to nine months in duration, because the cancer gets around the blockade put up by PLX4032, which targets the BRAF mutation found in 50 to 60 percent of melanoma patients.

Lo and his team spent two years studying tissue taken from patients enrolled in the Jonsson Cancer Center study to try to determine the mechanism of resistance. They also developed drug resistant cell lines to study, in collaboration with another team at UCLA's Jonsson Cancer Center led by Dr. Antoni Ribas, an associate professor of hematology/oncology

It had been theorized that BRAF was finding a way around the experimental drug by developing a secondary mutation. However, Lo determined that was not the case, an important finding because it means that second generation drugs targeting BRAF would not work and therefore should not be developed, saving precious time.

Lo said that while his team was studying resistance, they expected to find secondary mutations in BRAF.

"We were surprised that we couldn't find a single case where a secondary mutation in BRAF was driving drug resistance," said Lo, an assistant professor of dermatology. "In a big portion of cases where cancers acquire resistance to targeted drugs, the oncogene being targeted finds a way to get around the drug by developing other additional mutations."

Cancers, Lo said, are very adept at finding ways around the drugs being used to fight them.

"You hit it with an axe, but the cancer soon finds a way to mitigate the effects of the axe," he said.

Lo and his team found that these mutually exclusive mechanisms of acquired drug resistance account for about 40 percent of the patients who were treated with PLX4032 and later acquired resistance to it. In some cases, Lo found that the cancer cells began overexpressing a cell surface protein that created an alternate survival pathway for the cancer while the BRAF survival pathway was being blocked by PLX4032. In other cases, a second oncogene, NRAS, became mutated, allowing the cancer to short circuit the PLX4032-inhibited BRAF mutation and reactivate the BRAF survival pathway. PLX4032 does not target the NRAS mutation, so the cancer can begin to regrow.

Lo said he expects to find other mechanisms of resistance in the remaining 60 percent of relapsing patients where neither of the two new mechanisms were found.

"It's important to find all the mechanisms of acquired drug resistance in this type of melanoma and figure out how to target them using drugs designed to hit those specific mechanisms," he said. "We've found two mechanisms in two subsets of melanoma and we'll need different drugs to treat those two subsets."

Going forward, Lo and his team will study the resistance mechanisms of the two subsets discovered and any others uncovered later to perhaps find better targets for therapy. For example, targeting the cell surface protein overexpression may prove more difficult than finding what causes the overexpression further upstream and homing in on that.

"How does the cell surface receptor get turned on in the first place?" Lo said. "We need to trace it back to its origin, find out what machinery is turning it on and shut that down."

Lo's study is an example of the translational research focus at the Jonsson Cancer Center. The tissues from the patients in the clinic were studied in the lab, where Lo and his team found what was causing resistance in some cases. That information will be used to find drugs to target those mechanisms that will then be brought back into the clinic to be tested in clinical trials.

"Working with the patients and then working in the lab gives me a different perspective," Lo said. "When patients ask what will happen to them if the experimental drug stops working, we can tell them that we're working 24/7 in our laboratory to figure out why that happens and discover a way to stop it."

###

About 68,000 cases of melanoma will be diagnosed in Americans this year alone. Of those, more than 8,700 people will die. For patients with metastatic melanoma, like those in the Jonsson Cancer Center study, there are few effective treatments, so it's vital to come up with alternative therapies, Lo said.

The study was funded by the Dermatology Foundation, Burroughs Wellcome Fund, STOP CANCER Foundation, Margaret E. Early Medical Trust, Ian Copeland Memorial Melanoma Fund, V Foundation for Cancer Research, Melanoma Research Foundation, American Skin Association, Caltech-UCLA Joint Center for Translational Medicine and the Wesley Coyle Memorial Fund.

UCLA's Jonsson Comprehensive Cancer Center has more than 240 researchers and clinicians engaged in disease research, prevention, detection, control, treatment and education. One of the nation's largest comprehensive cancer centers, the Jonsson center is dedicated to promoting research and translating basic science into leading-edge clinical studies. In July 2010, the Jonsson Cancer Center was named among the top 10 cancer centers nationwide by U.S. News & World Report, a ranking it has held for 10 of the last 11 years. For more information on the Jonsson Cancer Center, visit our website at http://www.cancer.ucla.edu.

END

The past year has brought to light both the promise and the frustration of developing new drugs to treat melanoma, the most deadly form of skin cancer. Early clinical tests of a candidate drug aimed at a crucial cancer-causing gene revealed impressive results in patients whose cancers resisted all currently available treatments. Unfortunately, those effects proved short-lived, as the tumors invariably returned a few months later, able to withstand the same drug to which they first succumbed. Adding to the disappointment, the reasons behind these relapses were unclear.

Now, ...

Researchers appear to have an explanation for a longstanding question in HIV biology: how it is that the virus kills so many CD4 T cells, despite the fact that most of them appear to be "bystander" cells that are themselves not productively infected. That loss of CD4 T cells marks the progression from HIV infection to full-blown AIDS, explain the researchers who report their findings in studies of human tonsils and spleens in the November 24th issue of Cell, a Cell Press publication.

"In [infected] primary human tonsils and spleens, there is a profound depletion of CD4 ...

Researchers at the Faculty of Life Sciences (LIFE), University of Copenhagen, can now unveil the results of the world's largest diet study:

If you want to lose weight, you should maintain a diet that is high in proteins with more lean meat, low-fat dairy products and beans and fewer finely refined starch calories such as white bread and white rice. With this diet, you can also eat until you are full without counting calories and without gaining weight. Finally, the extensive study concludes that the official dietary recommendations are not sufficient for preventing obesity. ...

They are the largest fish species in the ocean, but the majestic gliding motion of the whale shark is, scientists argue, an astonishing feat of mathematics and energy conservation. In new research published today in the British Ecological Society's journal Functional Ecology marine scientists reveal how these massive sharks use geometry to enhance their natural negative buoyancy and stay afloat.

For most animals movement is crucial for survival, both for finding food and for evading predators. However, movement costs substantial amounts of energy and while this is true ...

An international team led by researchers from the Universities of Leicester and Cambridge has announced a breakthrough in identifying people at risk of developing potentially fatal blood clots that can lead to heart attack.

The discovery, published this week (25 November) in the leading haematology journal Blood, is expected to advance ways of detecting and treating coronary heart disease – the most common form of disease affecting the heart and an important cause of premature death.

The research led by Professor Alison Goodall from the University of Leicester and Professor ...

A new treatment has been developed for sudden sensorineural hearing loss (SSHL), a condition that causes deafness in 40,000 Americans each year, usually in early middle-age. Researchers writing in the open access journal BMC Medicine describe the positive results of a preliminary trial of insulin-like growth factor 1 (IGF1), applied as a topical gel.

Takayuki Nakagawa, from Kyoto University, Japan, worked with a team of researchers to test the gel in 25 patients whose SSHL had not responded to the normal treatment of systemic gluticosteroids. He said, "The results indicated ...

Every 5°C rise in maximum temperature pushes up the rate of hospital admissions for serious injuries among children, reveals one of the largest studies of its kind published online in Emergency Medicine Journal.

Conversely, each 5° C drop in the minimum daily temperature boosts adult admissions for serious injury by more than 3%, while snow prompts an 8% rise, the research shows.

The authors base their findings on the patterns of hospital treatment for both adults and children in 21 emergency care units across England, belonging to the Trauma Audit and research Network ...

Workplace asthma costs the UK at least £100 million a year, and may be as high as £135 million, reveals research published online in Thorax.

An estimated 3,000 new cases of occupational asthma are diagnosed every year in the UK, but the condition is under diagnosed, say the authors.

They reviewed published data on the costs of all asthma and workplace asthma, as well as the impact costs.

The evidence was then used to calculate the costs of workplace asthma on an individual's ability to work and their wider life, including their use of health services, based on a ...

New research from the Emory University School of Medicine offers reassurance for nursing mothers with epilepsy. According to a study published in the November 24 online issue of Neurology, the medical journal of the American Academy of Neurology, breastfeeding a baby while taking a seizure medication may have no harmful effect on the child's IQ later in life.

"Our results showed no difference in IQ scores between the children who were breastfed and those who were not," says study author Kimford Meador, MD, professor of neurology, Emory University School of Medicine and ...

Chronic jet lag alters the brain in ways that cause memory and learning problems long after one's return to a regular 24-hour schedule, according to research by University of California, Berkeley, psychologists.

Twice a week for four weeks, the researchers subjected female Syrian hamsters to six-hour time shifts – the equivalent of a New York-to-Paris airplane flight. During the last two weeks of jet lag and a month after recovery from it, the hamsters' performance on learning and memory tasks was measured.

As expected, during the jet lag period, the hamsters had trouble ...