(Press-News.org) MADISON, Wis. — As Dane County begins the long slide into winter and the days become frostier this fall, three spots stake their claim as the chilliest in the area.

One is a cornfield in a broad valley and two are wetlands. In contrast, the isthmus makes an island — an urban heat island.

In a new study published this month in the Journal of Applied Meteorology and Climatology, University of Wisconsin-Madison researchers highlight the urban heat island effect in Madison: The city's concentrated asphalt, brick and concrete lead to higher temperatures than its nonurban surroundings.

After collecting and analyzing more than two years of temperature and humidity data from a network of 151 sensors throughout the Madison region, they have found some of the area's hottest, and coldest, spots.

The study was aimed at helping the Madison region plan for the future, to think about the impacts of the structures and local environments it creates. As more people across the globe choose to live in cities and as existing cities expand and grow — particularly the small and midsize ones like Madison — understanding how development impacts people and the environment is crucial.

While warmer temperatures may sound nice this time of year, just months ago, that same heat may have been far less welcome. Combined with climate change, hotter cities impact the health, quality of life, and environment for all that live within them.

"Cities tend to be warmer than their rural surroundings; they retain more heat," says Jason Schatz, a graduate student in the Nelson Institute for Environmental Studies and affiliate of the Water Sustainability and Climate (WSC) project, who co-authored the study with WSC lead investigator, Chris Kucharik.

The take-home message: Local climates matter.

"Cities have experienced their own warming," says Kucharik, also a UW-Madison associate professor in the Department of Agronomy in the College of Agricultural and Life Sciences and with the Nelson Institute. "It's not a magnitude of change that can be easily dismissed."

The study is one of only a few to examine a city with fewer than 500,000 people and it created one of the most extensive climate sensor networks to date, the researchers say. Other cities may generate their own useful data with the methods they developed.

Additionally, because of the robustness of their data, the researchers were able to create a statistical tool to examine the relationship between air temperature and land cover. That data was freely available through the U.S. National Land Cover Database. Any city that can measure its air temperature can use the method.

In March 2012, Schatz worked with Dane County officials, local city governments, UW-Madison, Alliant Energy, and Madison Gas and Electric to install a network of sensors on utility poles throughout the region. The sensors collected data every 15 minutes.

Analyzing tens of thousands of data points, Schatz and Kucharik found the urban heat island effect peaked in summer, when downtown Madison averaged 7 degrees Fahrenheit warmer at night and 3 degrees warmer during the day when compared to rural Dane County.

In winter, the effect was smaller but snow cover played a role in an average 2 degree temperature difference between urban and rural areas. During the day, the percent of the area covered by snow had a strong impact, while at night, the depth of that snow cover was most important.

The study is one of the first to examine the relationship between snow cover and the urban heat island effect.

Cities are typically warmer than rural and suburban areas. Schatz and Kucharik suspect that increased vegetation in the region's rural areas accounts for the greater difference in temperature during the summer. Indeed, they found the magnitude of the urban heat island effect decreased toward the start of the fall harvest season, when vegetation is removed from farm fields, leaves fall from trees, and plants become less active.

The Madison region's coldest spots are likely that way because of the abundant vegetation they contain, their openness and their lower elevation. Cooler air tends to settle in low-lying areas, a phenomenon known as katabatic drainage.

As Madison and other cities contemplate future growth and development, the impact of the urban island effect should be part of the conversation, Schatz and Kucharik say, with the goal of making cities more livable and more resilient.

"Land-use discussions here are fundamental," says Schatz. "There is a lot Madison will have to decide in the coming decades."

INFORMATION:

The study was funded by the Water Sustainability and Climate Program of the National Science Foundation and a University of Wisconsin-Madison University Fellowship.

— Kelly April Tyrrell, ktyrrell2@wisc.edu, 608-262-9772

CONTACT: Jason Schatz, 608-263-1859, jschatz2@wisc.edu; Chris Kucharik, 608-263-1859 or 608-890-3021, kucharik@wisc.edu

BETHESDA, MD – Age-related loss of the Y chromosome (LOY) from blood cells, a frequent occurrence among elderly men, is associated with elevated risk of various cancers and earlier death, according to research presented at the American Society of Human Genetics (ASHG) 2014 Annual Meeting in San Diego.

This finding could help explain why men tend to have a shorter life span and higher rates of sex-unspecific cancers than women, who do not have a Y chromosome, said Lars Forsberg, PhD, lead author of the study and a geneticist at Uppsala University in Sweden.

LOY, ...

(Philadelphia, PA) – Chest pain doesn't necessarily come from the heart. An estimated 200,000 Americans each year experience non-cardiac chest pain, which in addition to pain can involve painful swallowing, discomfort and anxiety. Non-cardiac chest pain can be frightening for patients and result in visits to the emergency room because the painful symptoms, while often originating in the esophagus, can mimic a heart attack. Current treatment — which includes pain modulators such as selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRI) — has a partial 40 to 50 ...

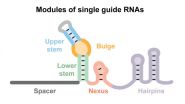

Customized genome editing – the ability to edit desired DNA sequences to add, delete, activate or suppress specific genes – has major potential for application in medicine, biotechnology, food and agriculture.

Now, in a paper published in Molecular Cell, North Carolina State University researchers and colleagues examine six key molecular elements that help drive this genome editing system, which is known as CRISPR-Cas.

NC State's Dr. Rodolphe Barrangou, an associate professor of food, bioprocessing and nutrition sciences, and Dr. Chase Beisel, an assistant ...

A longstanding question among scientists is whether evolution is predictable. A team of researchers from UC Santa Barbara may have found a preliminary answer. The genetic underpinnings of complex traits in cephalopods may in fact be predictable because they evolved in the same way in two distinct species of squid.

Last, year, UCSB professor Todd Oakley and then-Ph.D. student Sabrina Pankey profiled bioluminescent organs in two species of squid and found that while they evolved separately, they did so in a remarkably similar manner. Their findings are published today in ...

Research in recent years has shown that people associate specific facial traits with an individual's personality. For instance, people consistently rate faces that appear more feminine or that naturally appear happy as looking more trustworthy. In addition to trustworthiness, people also consistently associate competence, dominance, and friendliness with specific facial traits. According to an article published by Cell Press on October 21st in Trends in Cognitive Sciences, people rely on these subtle and arbitrary facial traits to make important decisions, from voting for ...

(SALT LAKE CITY)—Workers punching in for the graveyard shift may be better off not eating high-iron foods at night so they don't disrupt the circadian clock in their livers.

Disrupted circadian clocks, researchers believe, are the reason that shift workers experience higher incidences of type 2 diabetes, obesity and cancer. The body's primary circadian clock, which regulates sleep and eating, is in the brain. But other body tissues also have circadian clocks, including the liver, which regulates blood glucose levels.

In a new study in Diabetes online, University ...

DURHAM, N.H. –- Crewed missions to Mars remain an essential goal for NASA, but scientists are only now beginning to understand and characterize the radiation hazards that could make such ventures risky, concludes a new paper by University of New Hampshire scientists.

In a paper published online in the journal Space Weather, associate professor Nathan Schwadron of the UNH Institute for the Study of Earth, Oceans, and Space (EOS) and the department of physics says that due to a highly abnormal and extended lack of solar activity, the solar wind is exhibiting extremely ...

DURHAM, N.H. – Six percent of U.S. children and youth missed a day of school over the course of a year because they were the victim of violence or abuse at school. This was a major finding of a study on school safety by University of New Hampshire researchers published this month in the Journal of School Violence.

"This study really highlights the way school violence can interfere with learning," says lead author David Finkelhor, professor of sociology and director of the Crimes Against Children Research Center (CCRC) at UNH. "Too many kids are missing school ...

New research shows that a preservation technique known as sequential subnormothermic ex vivo liver perfusion (SNEVLP) prevents ischemic type biliary stricture following liver transplantation using grafts from donations after cardiac death (DCD). Findings published in Liver Transplantation, a journal of the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases and the International Liver Transplantation Society, indicate that the preservation of DCD grafts using SNEVLP versus cold storage reduces bile duct and endothelial cell injury post transplantation.

The shortage ...

VIDEO:

Scientists at the US Department of Energy's Ames Laboratory modeled the 'passing probability' of molecules within the narrow pores of mesoporous nanoparticles. This understanding will help determine the optimal diameter...

Click here for more information.

Scientists at the U.S. Department of Energy's Ames Laboratory have developed deeper understanding of the ideal design for mesoporous nanoparticles used in catalytic reactions, such as hydrocarbon conversion to biofuels. ...