Liquid helium offers a fascinating new way to make charged molecules

University of Leicester chemist involved in 'startling' new discovery

2014-10-24

(Press-News.org) A collaboration between researchers at the Universities of Leicester and Innsbruck has developed a completely new way of forming charged molecules which offers tremendous potential for new areas of chemical research.

Professor Andrew Ellis from our Department of Chemistry has been working for several years with colleagues at the Institute of Ion Physics in Austria on exploring the chemistry of molecules inside liquid helium. The team's latest and most startling discovery is that helium atoms can acquire an excess negative charge which enables them to become aggressive new chemical reagents.

Helium is a famously unreactive gas but when cooled to just above absolute zero it becomes a superfluid, a strange form of liquid. (Among other bizarre properties, liquid helium can flow upwards because it has zero viscosity and its capillary action is stronger than gravity.) The Anglo-Austrian team manufacture droplets of superfluid liquid helium by subjecting helium gas to a combination of high pressure and low temperature and then force it through a pinhole just 5 µm in diameter into a vacuum chamber. These droplets provide a controlled environment into which molecules can be added to study chemistry.

The molecules in this case were fullerenes, a class of large carbon molecules, named after their geometrical similarity to the geodesic spheres developed by architect Buckminster Fuller in the 1950s. The droplets of helium were passed through a cell containing C60 or C70 fullerenes and the resultant mixture was hit by an electron beam of energy between 0 and 150 eV.

What Professor Ellis and his colleagues discovered was that clusters of five or more fullerene molecules became dianions (gained a double negative charge) when targeted by a beam of about 22 eV. Dianions are not uncommon in chemistry but they are normally very unstable and short-lived outside of common chemical solutions (such as water). The creation of relatively stable fullerene dianions in liquid helium opens up a whole new research area for chemists.

So how have these dianions come about? Adding two electrons sequentially to something is difficult because of Coulomb's Law: the negative charge of the first electron will tend to repel the second electron. What has evidently happened is that two electrons have attached themselves to a fullerene molecule simultaneously. The key question is where do these two electrons come from and why don't they repel each other?

The answer seems to lie with helium. Helium atoms have two electrons in their natural, neutral state, their negative charge being balanced by two positively charged protons. The first orbit or shell around an atomic nucleus can only hold two electrons, which is why helium is generally disinterested in reacting with anything.

However, in these new experiments an electron beam with the right energy excites one of these electrons, causing it jump up to the next orbit where it is joined by an electron from the beam, creating an anion of helium. There are now two electrons in large orbits around the helium nucleus which makes this helium anion very reactive. When a suitably sized target, such as a clump of fullerene molecules, presents itself the two outer electrons jump ship, ending up on the fullerene. This pairing of two electrons which would normally repel each other is most likely aided by the very low temperature (0.4 K) inside the helium droplets and has echoes of the behaviour of electron pairs in superconductors.

Professor Ellis said: "Nothing like this has been observed before and the idea of helium as an electron donor is something completely new. This is really just the beginning of a new branch of chemistry and our research team is now exploring how other chemical processes might be influenced by this remarkable chemical reagent."

INFORMATION:

The paper 'Formation of Dianions in Helium Droplets' by Mauracher at al has been published (in English) in the international journal Angewandte Chemie. This work was funded by the European Union and the Austrian Science Foundation (FWF).

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

2014-10-24

The critically endangered Saimaa ringed seal, which inhabits Lake Saimaa in Finland, has extremely low genetic diversity and this development seems to continue, according to a recent study completed at the University of Eastern Finland. In her doctoral dissertation, Mia Valtonen, MSc, analysed the temporal and regional variation in the genetic diversity of the endangered Saimaa ringed seal. The population is only around 300 individuals divided into smaller sub-populations and with very little migration among between them.

The study developed a method allowing the identification ...

2014-10-24

BUFFALO, N.Y. — A new study is helping to rewrite Ebola's family history.

The research shows that filoviruses — a family to which Ebola and its similarly lethal relative, Marburg, belong — are at least 16-23 million years old.

Filoviruses likely existed in the Miocene Epoch, and at that time, the evolutionary lines leading to Ebola and Marburg had already diverged, the study concludes.

The research was published in the journal PeerJ in September. It adds to scientists' developing knowledge about known filoviruses, which experts once believed came ...

2014-10-24

Adherent cells, the kind that form the architecture of all multi-cellular organisms, are mechanically engineered with precise forces that allow them to move around and stick to things. Proteins called integrin receptors act like little hands and feet to pull these cells across a surface or to anchor them in place. When groups of these cells are put into a petri dish with a variety of substrates they can sense the differences in the surfaces and they will "crawl" toward the stiffest one they can find.

Now chemists have devised a method using DNA-based tension probes to ...

2014-10-24

Tempe, Ariz. (Oct. 23, 2014) - New research findings from a team of prevention scientists at Arizona State University demonstrates that a family-focused intervention program for middle-school Mexican American children leads to fewer drop-out rates and lower rates of alcohol and illegal drug use.

"This is the first randomized prevention trial that we're aware of to show effects on school dropout for this population," said Nancy Gonzales, Foundation Professor in the REACH Institute and Psychology Department, College of Liberal Arts and Sciences at Arizona State University. ...

2014-10-24

RIVERSIDE, Calif. – Plant breeders have long identified and cultivated disease-resistant varieties. A research team at the University of California, Riverside has now revealed a new molecular mechanism for resistance and susceptibility to a common fungus that causes wilt in susceptible tomato plants.

Study results appeared Oct. 16 in PLOS Pathogens.

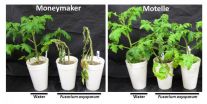

Katherine Borkovich, a professor of plant pathology and the chair of the Department of Plant Pathology and Microbiology, and colleagues started with two closely related tomato cultivars: "Moneymaker" is susceptible ...

2014-10-24

ORLANDO, Fla. – New research shows obese children with asthma may mistake symptoms of breathlessness for loss of asthma control leading to high and unnecessary use of rescue medications. The study was published online in the Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology (JACI), the official scientific journal of the American Association of Allergy, Asthma and Immunology.

"Obese children with asthma need to develop a greater understanding of the distinct feeling of breathlessness in order to avoid not just unnecessary medication use, but also the anxiety, reduced quality ...

2014-10-24

Just three years ago, a patient at Sahlgrenska University Hospital received a blood vessel transplant grown from her own stem cells.

Suchitra Sumitran-Holgersson, Professor of Transplantation Biology at The Univerisity of Gothenburg, and Michael Olausson, Surgeon/Medical Director of the Transplant Center and Professor at Sahlgrenska Academy, came up with the idea, planned and carried out the procedure.

Missing a vein

Professors Sumitran-Holgersson and Olausson have published a new study in EBioMedicine based on two other transplants that were performed in 2012 at Sahlgrenska ...

2014-10-24

Gossip is pervasive in our society, and our penchant for gossip can be found in most of our everyday conversations. Why are individuals interested in hearing gossip about others' achievements and failures? Researchers at the University of Groningen in the Netherlands studied the effect positive and negative gossip has on how the recipient evaluates him or herself. The study is published in Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin.

In spite of some positive consequences, gossip is typically seen as destructive and negative. However, hearing gossip may help individuals ...

2014-10-24

New data shows that healthcare and personal costs to support survivors of stroke remains high 10 years on.

The Monash University research, published today in the journal Stroke, is the first to look at the long-term costs for the two main causes of stroke; ischemic where the blood supply stops due to a blood clot, and hemorrhagic, which occurs when a weakened blood vessel supplying the brain bursts.

Previous studies based on estimating the lifetime costs using patient data up to 5 years after a stroke, suggested that costs peaked in the first year and then declined ...

2014-10-24

Metamaterials, a hot area of research today, are artificial materials engineered with resonant elements to display properties that are not found in natural materials. By organizing materials in a specific way, scientists can build materials with a negative refractivity, for example, which refract light at a reverse angle from normal materials. However, metamaterials up to now have harbored a significant downside. Unlike natural materials, they are two-dimensional and inherently anisotropic, meaning that they are designed to act in a certain direction. By contrast, three-dimensional ...

LAST 30 PRESS RELEASES:

[Press-News.org] Liquid helium offers a fascinating new way to make charged molecules

University of Leicester chemist involved in 'startling' new discovery