(Press-News.org) DURHAM, N.C. – Frogs are well-known for being among the loudest amphibians, but new research indicates that the development of this trait followed another: bright coloration. Scientists have found that the telltale colors of some poisonous frog species established them as an unappetizing option for would-be predators before the frogs evolved their elaborate songs. As a result, these initial warning signals allowed different species to diversify their calls over time.

Zoologists at the National Evolutionary Synthesis Center (NESCent), the University of British Columbia, and other research universities assembled an acoustic database to analyze more than 16,000 calls from 172 species within the poison frog family, Dendrobatidae. The paper, which will appear in the December issue of the Proceedings of the Royal Society B, is now available online.

The study included both frogs that display bright colors and others that rely on camouflage for protection. Each call was examined in terms of pitch and duration, and researchers also factored in the size of the frogs and their visibility to predators. They found that because warning coloration protected them from predators, they were better able to attract a mate with low-pitch, pulsing vocalizations in plain sight than their quieter, darker-hued relatives.

"This allows the frog to have a unique type of call—a noisy call," said lead author Juan C. Santos, formerly of NESCent and now at the University of British Columbia. "These noisy kinds of calls, in general, are what the females really like."

Scientists already understood that predators shied away from brightly colored frogs because of visual cues, but Santos and his colleagues hypothesized that some species evolved to include audio signals, as well. Such a warning system is not unprecedented: Tiger moths emit ultrasonic chirps to communicate their unsavory taste to bats. Without a similar ability, frogs navigate a precarious dilemma in which they must either risk detection by predators or forgo possible courtship.

Initially the researchers expected that audio warnings predated coloration, but the results indicate the opposite. Using molecular data and statistical analyses, they were able to infer a phylogenetic tree and pinpoint which trait came first. Their findings indicate that visual traits established the frogs as poisonous and cleared the way for louder, more elaborate calls.

Species relying on camouflage for defense will not invite attention with boisterous calls, while their protected relatives—including nonpoisonous frogs that mimic the appearance of their toxic counterparts— can be loud and more nuanced.

"The type of color they have is in the range of the noisy ones," Santos said. "When you're mimicking somebody that's already protected, you have some freedom to be found by potential mates."

These calls require high energy expenditures, but the boon of attracting females without predatory threats makes it a rewarding behavior for males. Less is known about the reasons females are attracted to the noisier males and how they appraise the various calls. Santos explained that if the females are being especially picky, it will drive male diversity by pushing them to create even more complex songs.

"What can the females get from this information? Maybe females— by being very picky— increase male diversity," Santos said. A more diverse pool of potential mates increases the likelihood that their offspring will have more advantageous genes over time.

INFORMATION:

This work was supported by the National Science Foundation (DEB: 0949899), the National Evolutionary Synthesis Center (NSF EF-0905606 and EF-0423641), and the University of Texas and the Amphibian Tree of Life project (NSF EF-0334952).

Santos, Juan C. et al. (2014). "Aposematism increases acoustic diversification and speciation in poison frogs" Proceedings of the Royal Society B. http://rspb.royalsocietypublishing.org/content/281/1796/20141761.abstract

The National Evolutionary Synthesis Center (NESCent) is a nonprofit science center dedicated to cross-disciplinary research in evolution. Funded by the National Science Foundation, NESCent is jointly operated by Duke University, The University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, and North Carolina State University. For more information about research and training opportunities at NESCent, visit http://www.nescent.org.

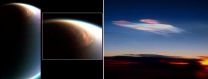

NASA scientists have identified an unexpected high-altitude methane ice cloud on Saturn's moon Titan that is similar to exotic clouds found far above Earth's poles.

This lofty cloud, imaged by NASA's Cassini spacecraft, was part of the winter cap of condensation over Titan's north pole. Now, eight years after spotting this mysterious bit of atmospheric fluff, researchers have determined that it contains methane ice, which produces a much denser cloud than the ethane ice previously identified there.

"The idea that methane clouds could form this high on Titan is completely ...

In a study just published in the International Journal of Cardiology, researchers from the K.G. Jebsen Center for Exercise in Medicine – Cardiac Exercise Research Group (CERG) at the Norwegian University of Science and Technology (NTNU) and the Department of Cardiothoracic Surgery at the St. Olavs Hospital in Trondheim, Norway have shown that shutting off the blood supply to an arm or leg before cardiac surgery protects the heart during the operation.

The research group wanted to see how the muscle of the left chamber of the heart was affected by a technique, called ...

Endurance athletes taking part in triathlons are at risk of the potentially life-threatening condition of swimming-induced pulmonary oedema. Cardiologists from Musgrove Park Hospital, Taunton, writing in the Journal of the Royal Society of Medicine, say the condition, which causes an excess collection of watery fluid in the lungs, is likely to become more common with the increase in participation in endurance sports. Increasing numbers of cases are being reported in community triathletes and army trainees. Episodes are more likely to occur in highly fit individuals undertaking ...

Six Case Western Reserve scientists are part of an international team that has discovered two compounds that show promise in decreasing inflammation associated with diseases such as ulcerative colitis, arthritis and multiple sclerosis. The compounds, dubbed OD36 and OD38, specifically appear to curtail inflammation-triggering signals from RIPK2 (serine/threonine/tyrosine kinase 2). RIPK2 is an enzyme that activates high-energy molecules to prompt the immune system to respond with inflammation. The findings of this research appear in the Journal of Biological Chemistry.

"This ...

Newly published findings from the University of Waterloo are giving women with bad backs renewed hope for better sex lives. The findings—part of the first-ever study to document how the spine moves during sex—outline which sex positions are best for women suffering from different types of low-back pain. The new recommendations follow on the heels of comparable guidelines for men released last month.

Published in European Spine Journal, the female findings debunk the popular belief that spooning—where couples lie on their sides curled in the same direction—is ...

Down syndrome is the most common chromosomal abnormality in humans, involving a third copy of all or part of chromosome 21. In addition to intellectual disability, individuals with Down syndrome have a high risk of congenital heart defects. However, not all people with Down syndrome have them – about half have structurally normal hearts.

Geneticists have been learning about the causes of congenital heart defects by studying people with Down syndrome. The high risk for congenital heart defects in this group provides a tool to identify changes in genes, both on and ...

In early drug discovery, you need a starting point, says Northeastern University associate professor of chemistry and chemical biology Michael Pollastri.

In a new research paper published Thursday in the journal PLOS Neglected Tropical Diseases, Pollastri and his colleagues present hundreds of such starting points for potentially treating African sleeping sickness, a deadly disease that claims thousands of lives annually.

Pollastri, who runs Northeastern's Laboratory for Neglected Disease Drug Discovery, ...

WASHINGTON – October 24, 2014 – Policy options for climate change risk management are straightforward and have well understood strengths and weaknesses, according to a new study by the American Meteorological Society (AMS) Policy Program.

"Large gaps remain in society's consideration of climate policy," said Paul Higgins, the author of the study. "This study can help in the development of a comprehensive strategy for climate change risk management because it explores a much larger set of policy options."

The study identifies four categories of climate ...

Washington, D.C., October 24, 2014 -- Only 6 percent of U.S. hospitals are well-prepared to receive a patient with the Ebola virus, according to a survey of infection prevention experts at U.S. hospitals conducted October 10-15 by the Association for Professionals in Infection Control and Epidemiology (APIC).

The survey asked APIC's infection preventionist members, "How prepared is your facility to receive a patient with the Ebola virus?" Of the 1,039 U.S.-based respondents working in acute care hospitals, about 6 percent reported their facility was well-prepared, while ...

LAWRENCE – 'Call your mother' may be the familiar refrain, but research from the University of Kansas shows that being able to text, email and Facebook dad may be just as important for young adults.

Jennifer Schon, a doctoral student in communication studies, found that adult children's relationship satisfaction with their parents is modestly influenced by the number of communication tools, such as cell phones, email, social networking sites, they use to communicate.

Schon had 367 adults between the ages of 18 and 29 fill out a survey on what methods of communications ...