(Press-News.org) Toronto, Canada – Making mistakes while learning can benefit memory and lead to the correct answer, but only if the guesses are close-but-no-cigar, according to new research findings from Baycrest Health Sciences.

"Making random guesses does not appear to benefit later memory for the right answer , but near-miss guesses act as stepping stones for retrieval of the correct information – and this benefit is seen in younger and older adults," says lead investigator Andrée-Ann Cyr, a graduate student with Baycrest's Rotman Research Institute and the Department of Psychology at the University of Toronto.

Cyr's paper is posted online today in the Journal of Experimental Psychology: Learning, Memory, and Cognition (ahead of print publication). The study expands upon a previous paper she published in Psychology and Aging in 2012 that found that learning information the hard way by making mistakes (as opposed to just being told the correct answer) may be the best boot camp for older brains.

That paper raised eyebrows since the scientific literature has traditionally recommended that older adults avoid making mistakes – unlike their younger peers who actually benefit from them. But recent evidence from Cyr and other researchers is challenging this perspective and prompting professional educators and cognitive rehabilitation clinicians to take note.

Cyr's latest research provides evidence that trial-and-error learning can benefit memory in both young and old when errors are meaningfully related to the right answer, and can actually harm memory when they are not.

In their latest study, 65 healthy younger adults (average age 22) and 64 healthy older adults (average age 72) learned target words (e.g., rose) based either on the semantic category it belongs to (e.g., a flower) or its word stem (e.g., a word that begins with the letters 'ro'). For half of the words, participants were given the answer right away (e.g., "the answer is rose") and for the other half, they were asked to guess at it before seeing the answer (e.g., a flower: "Is it tulip?" or ro___ : "is it rope?").

On a later memory test, participants were shown the categories or word stems and had to come up with the right answer. The researchers wanted to know if participants would be better at remembering rose if they had made wrong guesses prior to studying it rather than seeing it right away. They found that this was only true if participants learned based on the categories (e.g., a flower). Guessing actually made memory worse when words were learned based on word stems (e.g., ro___). This was the case for both younger and older adults. Cyr and her colleagues suggest this is because our memory organizes information based on how it is conceptually rather than lexically related to other information. For example, when you think of the word pear, your mind is more likely to jump to another fruit, such as apple, than to a word that looks similar, such as peer. Wrong guesses only add value when they have something meaningful in common with right answers. The guess tulip may be wrong, but it is still conceptually close to the right answer rose (both are flowers).

By guessing first as opposed to just reading the answer, one is thinking harder about the information and making useful connections that can help memory. Indeed, younger and older participants were more likely to remember the answer if they also remembered their wrong guesses, suggesting that these acted as stepping stones. By contrast, when guesses only have letters in common with answers, they clutter memory because one cannot link them meaningfully. The word rope is nowhere close to rose in our memory. In these situations, where your guesses are likely to be out in left field, it is best to bypass mistakes altogether.

"The fact that this pattern was found for older adults as well shows that aging does not influence how we learn from mistakes," says Cyr.

"These results have profound clinical and practical implications. They turn traditional views of best practices in memory rehabilitation for healthy seniors on their head by demonstrating that making the right kind of errors can be beneficial. They also provide great hope for lifelong learning and guidance for how seniors should study," says Dr. Nicole Anderson, senior scientist with Baycrest's Rotman Research Institute and senior author on the study.

INFORMATION:

The study was funded by the Canadian Institutes of Health Research.

VANCOUVER ─ Different ethnic groups have widely varying differences in both the prevalence and awareness of cardiovascular risk factors, a finding that highlights the need for specially designed education and intervention programs, according to a study presented today at the 2014 Canadian Cardiovascular Congress.

The conclusion comes from a study of more than 3,000 patients at an urgent-care clinic serving an ethnically diverse area of Toronto. Participants were asked to self-identify their ethnicity and, from a list of 20 activities or conditions, asked to identify ...

VANCOUVER ─ People facing mental health challenges are significantly more likely to have heart disease or stroke, according to a study presented today at the Canadian Cardiovascular Congress.

"This population is at high risk, and it's even greater for people with multiple mental health issues," says Dr. Katie Goldie, lead author of the study and a postdoctoral fellow at the Centre for Addiction and Mental Health in Toronto

Using data from the Canadian Community Health Survey, Dr. Goldie explored the associations between cardiovascular risk and disease, mental ...

VANCOUVER ─ Heart surgery patients who received newly donated blood have significantly fewer post-operative complications than those who received blood that had been donated more than two weeks before their surgery, a study presented at the Canadian Cardiovascular Congress has shown.

The study examined records at the New Brunswick Heart Centre (NBHC) in Saint John for non-emergency heart surgeries performed over almost nine years, from January 2005 to September 2013, on patients who received red blood cells either during their surgery or afterwards and who stayed ...

This news release is available in French.

In less than a minute, a miniature device developed at the University of Montreal can measure a patient's blood for methotrexate, a commonly used but potentially toxic cancer drug. Just as accurate and ten times less expensive than equipment currently used in hospitals, this nanoscale device has an optical system that can rapidly gauge the optimal dose of methotrexate a patient needs, while minimizing the drug's adverse effects. The research was led by Jean-François Masson and Joelle Pelletier of the university's Department ...

In an analysis that included approximately 35,000 participants, genetic predisposition to elevated low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL-C) was associated with aortic valve calcium and narrowing of the aortic valve, findings that support a causal association between LDL-C and aortic valve disease, according to a study appearing in JAMA. The study is being released to coincide with its presentation at the Canadian Cardiovascular Congress.

Aortic valve disease remains the most common form of heart valve disease in Europe and North America and is the most common indication ...

Stanford, CA— Proteins are the machinery that accomplishes almost every task in every cell in every living organism. The instructions for how to build each protein are written into a cell's DNA. But once the proteins are constructed, they must be shipped off to the proper place to perform their jobs. New work from a team of scientists led by Carnegie's Munevver Aksoy and Arthur Grossman, describes a potentially new pathway for targeting newly manufactured proteins to the correct location. Their work is published by The Plant Cell.

The team's discovery concerns ...

October 26, 2014, New York, NY – Ludwig Oxford researchers have discovered a key mechanism that governs how cells of the epithelia, the soft lining of inner body cavities, shift between a rigid, highly structured and immobile state and a flexible and motile form. Published in the current issue of Nature Cell Biology, their study shows that a tumor suppressor protein named ASPP2 functions as a molecular switch that controls this process and its reverse, both of which play a critical role in a number of biological phenomena, including wound healing, embryonic development ...

PROVIDENCE, R.I. [Brown University] — Superconductors and magnetic fields do not usually get along. But a research team led by a Brown University physicist has produced new evidence for an exotic superconducting state, first predicted a half-century ago, that can indeed arise when a superconductor is exposed to a strong magnetic field.

"It took 50 years to show that this phenomenon indeed happens," said Vesna Mitrovic, associate professor of physics at Brown University, who led the work. "We have identified the microscopic nature of this exotic quantum state of ...

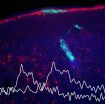

Scientists have created cells with fluorescent dyes that change color in response to specific neurochemicals. By implanting these cells into living mammalian brains, they have shown how neurochemical signaling changes as a food reward drives learning, they report in Nature Methods online October 26.

These cells, called CNiFERs (pronounced "sniffers"), can detect small amounts of a neurotransmitter, either dopamine or norepinephrine, with fine resolution in both location and timing. Dopamine has long been of interest to neuroscientists for its role in learning, reward, ...

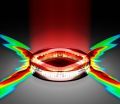

Lasers – devices that deliver beams of highly organized light – are so deeply integrated into modern technology that their basic operations would seem well understood. CD players, medical diagnostics and military surveillance all depend on lasers.

Re-examining longstanding beliefs about the physics of these devices, Princeton engineers have now shown that carefully restricting the delivery of power to certain areas within a laser could boost its output by many orders of magnitude. The finding, published Oct. 26 in the journal Nature Photonics, could allow ...