(Press-News.org) PROVIDENCE, R.I. [Brown University] — Superconductors and magnetic fields do not usually get along. But a research team led by a Brown University physicist has produced new evidence for an exotic superconducting state, first predicted a half-century ago, that can indeed arise when a superconductor is exposed to a strong magnetic field.

"It took 50 years to show that this phenomenon indeed happens," said Vesna Mitrovic, associate professor of physics at Brown University, who led the work. "We have identified the microscopic nature of this exotic quantum state of matter."

The research is published in Nature Physics.

Superconductivity — the ability to conduct electric current without resistance — depends on the formation of electron twosomes known as Cooper pairs (named for Leon Cooper, a Brown University physicist who shared the Nobel Prize for identifying the phenomenon). In a normal conductor, electrons rattle around in the structure of the material, which creates resistance. But Cooper pairs move in concert in a way that keeps them from rattling around, enabling them to travel without resistance.

Magnetic fields are the enemy of Cooper pairs. In order to form a pair, electrons must be opposites in a property that physicists refer to as spin. Normally, a superconducting material has a roughly equal number of electrons with each spin, so nearly all electrons have a dance partner. But strong magnetic fields can flip "spin-down" electrons to "spin-up", making the spin population in the material unequal.

"The question is what happens when we have more electrons with one spin than the other," Mitrovic said. "What happens with the ones that don't have pairs? Can we actually form superconducting states that way, and what would that state look like?"

In 1964, physicists predicted that superconductivity could indeed persist in certain kinds of materials amid a magnetic field. The prediction was that the unpaired electrons would gather together in discrete bands or stripes across the superconducting material. Those bands would conduct normally, while the rest of the material would be superconducting. This modulated superconductive state came to be known as the FFLO phase, named for theorists Peter Fulde, Richard Ferrell, Anatoly Larkin, and Yuri Ovchinniko, who predicted its existence.

To investigate the phenomenon, Mitrovic and her team used an organic superconductor with the catchy name κ-(BEDT-TTF)2Cu(NCS)2. The material consists of ultra-thin sheets stacked on top of each other and is exactly the kind of material predicted to exhibit the FFLO state.

After applying an intense magnetic field to the material, Mitrovic and her collaborators from the French National High Magnetic Field Laboratory in Grenoble probed its properties using nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR).

What they found were regions across the material where unpaired, spin-up electrons had congregated. These "polarized" electrons behave, "like little particles constrained in a box," Mitrovic said, and they form what are known as Andreev bound states.

"What is remarkable about these bound states is that they enable transport of supercurrents through non-superconducting regions," Mitrovic said. "Thus, the current can travel without resistance throughout the entire material in this special superconducting state."

Experimentalists have been trying for years to provide solid evidence that the FFLO state exists, but to little avail. Mitrovic and her colleagues took some counterintuitive measures to arrive at their findings. Specifically, they probed their material at a much higher temperature than might be expected for quantum experiments.

"Normally to observe quantum states you want to be as cold as possible, to limit thermal motion," Mitrovic said. "But by raising the temperature we increased the energy window of our NMR probe to detect the states we were looking for. That was a breakthrough."

This new understanding of what happens when electron spin populations become unequal could have implications beyond superconductivity, according to Mitrovic.

It might help astrophysicists to understand pulsars — densely packed neutron stars believed to harbor both superconductivity and strong magnetic fields. It could also be relevant to the field of spintronics, devices that operate based on electron spin rather than charge, made of layered ferromagnetic-superconducting structures.

"This really goes beyond the problem of superconductivity," Mitrovic said. "It has implications for explaining many other things in the universe, such as behavior of dense quarks, particles that make up atomic nuclei."

INFORMATION:

Note to Editors:

Editors: Brown University has a fiber link television studio available for domestic and international live and taped interviews, and maintains an ISDN line for radio interviews. For more information, call (401) 863-2476.

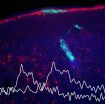

Scientists have created cells with fluorescent dyes that change color in response to specific neurochemicals. By implanting these cells into living mammalian brains, they have shown how neurochemical signaling changes as a food reward drives learning, they report in Nature Methods online October 26.

These cells, called CNiFERs (pronounced "sniffers"), can detect small amounts of a neurotransmitter, either dopamine or norepinephrine, with fine resolution in both location and timing. Dopamine has long been of interest to neuroscientists for its role in learning, reward, ...

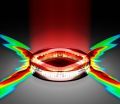

Lasers – devices that deliver beams of highly organized light – are so deeply integrated into modern technology that their basic operations would seem well understood. CD players, medical diagnostics and military surveillance all depend on lasers.

Re-examining longstanding beliefs about the physics of these devices, Princeton engineers have now shown that carefully restricting the delivery of power to certain areas within a laser could boost its output by many orders of magnitude. The finding, published Oct. 26 in the journal Nature Photonics, could allow ...

NEW YORK, NY (October 26, 2014)—Dietary cocoa flavanols—naturally occurring bioactives found in cocoa—reversed age-related memory decline in healthy older adults, according to a study led by Columbia University Medical Center (CUMC) scientists. The study, published today in the advance online issue of Nature Neuroscience, provides the first direct evidence that one component of age-related memory decline in humans is caused by changes in a specific region of the brain and that this form of memory decline can be improved by a dietary intervention.

As ...

MOUNT WILSON, Calif.–Astronomers at Georgia State University's Center for High Angular Resolution Astronomy (CHARA) have observed the expanding thermonuclear fireball from a nova that erupted last year in the constellation Delphinus with unprecedented clarity.

The observations produced the first images of a nova during the early fireball stage and revealed how the structure of the ejected material evolves as the gas expands and cools. It appears the expansion is more complicated than simple models previously predicted, scientists said. The results of these observations, ...

BOSTON –– Scientists say they have identified in about 20 percent of colorectal and endometrial cancers a genetic mutation that had been overlooked in recent large, comprehensive gene searches. With this discovery, the altered gene, called RNF43, now ranks as one of the most common mutations in the two cancer types.

Reporting in the October 26, 2014 edition of Nature Genetics, investigators from Dana-Farber Cancer Institute and the Broad Institute of MIT and Harvard said the mutated gene helps control an important cell-signaling pathway, Wnt, that has been ...

Why do we remember some things and not others? In a unique imaging study, two Northwestern University researchers have discovered how neurons in the brain might allow some experiences to be remembered while others are forgotten. It turns out, if you want to remember something about your environment, you better involve your dendrites.

Using a high-resolution, one-of-a-kind microscope, Daniel A. Dombeck and Mark E. J. Sheffield peered into the brain of a living animal and saw exactly what was happening in individual neurons called place cells as the animal navigated a virtual ...

Digoxin, a medication used in the treatment of heart failure, may be adaptable for the treatment of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS), a progressive, paralyzing disease, suggests new research at Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis.

ALS, also known as Lou Gehrig's disease, destroys the nerve cells that control muscles. This leads to loss of mobility, difficulty breathing and swallowing and eventually death. Riluzole, the sole medication approved to treat the disease, has only marginal benefits in patients.

But in a new study conducted in cell cultures ...

CHAMPAIGN, Ill. — Researchers report in the journal Nature that they have made a breakthrough in understanding how a powerful antibiotic agent is made in nature. Their discovery solves a decades-old mystery, and opens up new avenues of research into thousands of similar molecules, many of which are likely to be medically useful.

The team focused on a class of compounds that includes dozens with antibiotic properties. The most famous of these is nisin, a natural product in milk that can be synthesized in the lab and is added to foods as a preservative. Nisin has ...

Most of the concerns about climate change have focused on the amount of greenhouse gases that have been released into the atmosphere.

But in a new study published in Science, a group of Rutgers researchers have found that circulation of the ocean plays an equally important role in regulating the earth's climate.

In their study, the researchers say the major cooling of Earth and continental ice build-up in the Northern Hemisphere 2.7 million years ago coincided with a shift in the circulation of the ocean – which pulls in heat and carbon dioxide in the Atlantic ...

DENVER – A better survival outcome is associated with low blood levels of squamous cell carcinoma antigen, or absence of tumor invasion either into the space between the lungs and chest wall or into blood vessels of individuals with a peripheral squamous cell carcinoma, a type of non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC).

Lung cancer is the most common cause of cancer-related death worldwide and lung squamous cell carcinomas (SCC) account for 20-30% of all NSCLC. SCC can be classified as either central (c-SCC) or peripheral (p-SCC) depending on the primary location. While ...