(Press-News.org) CHAMPAIGN, Ill. — Researchers report in the journal Nature that they have made a breakthrough in understanding how a powerful antibiotic agent is made in nature. Their discovery solves a decades-old mystery, and opens up new avenues of research into thousands of similar molecules, many of which are likely to be medically useful.

The team focused on a class of compounds that includes dozens with antibiotic properties. The most famous of these is nisin, a natural product in milk that can be synthesized in the lab and is added to foods as a preservative. Nisin has been used to combat food-borne pathogens since the late 1960s.

Researchers have long known the sequence of the nisin gene, and they can assemble the chain of amino acids (called a peptide) that are encoded by this gene. But the peptide undergoes several modifications in the cell after it is made, changes that give it its final form and function. Researchers have tried for more than 25 years to understand how these changes occur.

"Peptides are a little bit like spaghetti; they're too flexible to do their jobs," said University of Illinois chemistry professor Wilfred van der Donk, who led the research with biochemistry professor Satish K. Nair. "So what nature does is it starts putting knobs in, or starts making the peptide cyclical."

Special enzymes do this work. For nisin, an enzyme called a dehydratase removes water to help give the antibiotic its final, three-dimensional shape. This is the first step in converting the spaghetti-like peptide into a five-ringed structure, van der Donk said.

The rings are essential to nisin's antibiotic function: Two of them disrupt the construction of bacterial cell walls, while the other three punch holes in bacterial membranes. This dual action is especially effective, making it much more difficult for microbes to evolve resistance to the antibiotic.

Previous studies showed that the dehydratase was involved in making these modifications, but researchers have been unable to determine how it did so. This lack of insight has prevented the discovery, production and study of dozens of similar compounds that also could be useful in fighting food-borne diseases or dangerous microbial infections, van der Donk said.

Through a painstaking process of elimination, Manuel Ortega, a graduate student in van der Donk's lab, established that the amino acid glutamate was essential to nisin's transformation.

"They discovered that the dehydratase did two things," Nair said. "One is that it added glutamate (to the nisin peptide), and the second thing it did was it eliminated glutamate. But how does one enzyme have two different activities?"

To help answer this question, Yue Hao, a graduate student in Nair's lab, used X-ray crystallography to visualize how the dehydratase bound to the nisin peptide. She found that the enzyme interacted with the peptide in two ways: It grasped one part of the peptide and held it fast, while a different part of the dehydratase helped install the ring structures.

"There's a part of the nisin precursor peptide that is held steady, and there's a part that is flexible. And the flexible part is actually where the chemistry is carried out," Nair said.

Ortega also made another a surprising discovery: transfer-RNA, a molecule best known for its role in protein production, supplies the glutamate that allows the dehydratase to help shape the nisin into its final, active form.

"In this study, we solve a lot of questions that people have had about how dehydration works on a chemical level," van der Donk said. "And it turns out that in nature a fairly large number of natural products – many of them with therapeutic potential – are made in a similar fashion. This really is like turning on a light where it was dark before, and now we and other labs can do all kinds of things that we couldn't do previously."

INFORMATION:

Van der Donk is a Howard Hughes Medical Institute investigator. He and Nair also are faculty in the Institute for Genomic Biology at Illinois.

The National Institute of General Medical Sciences at the National Institutes of Health and the Ford Foundation supported this work.

To reach Satish Nair, call 217-333-0641; email snair@illinois.edu.

To reach Wilfred van der Donk, call 217-244-5360; email vddonk@illinois.edu.

The paper, "Structure and mechanism of the tRNA-dependent lantibiotic dehydratase NisB," is available online or to members of the media from the U. of I. News Bureau.

Most of the concerns about climate change have focused on the amount of greenhouse gases that have been released into the atmosphere.

But in a new study published in Science, a group of Rutgers researchers have found that circulation of the ocean plays an equally important role in regulating the earth's climate.

In their study, the researchers say the major cooling of Earth and continental ice build-up in the Northern Hemisphere 2.7 million years ago coincided with a shift in the circulation of the ocean – which pulls in heat and carbon dioxide in the Atlantic ...

DENVER – A better survival outcome is associated with low blood levels of squamous cell carcinoma antigen, or absence of tumor invasion either into the space between the lungs and chest wall or into blood vessels of individuals with a peripheral squamous cell carcinoma, a type of non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC).

Lung cancer is the most common cause of cancer-related death worldwide and lung squamous cell carcinomas (SCC) account for 20-30% of all NSCLC. SCC can be classified as either central (c-SCC) or peripheral (p-SCC) depending on the primary location. While ...

VIDEO:

On Oct. 23, while North America was witnessing a partial eclipse of the sun, the Hinode spacecraft observed a 'ring of fire' or annular eclipse from its location hundreds of...

Click here for more information.

The moon passed between the Earth and the sun on Thursday, Oct. 23. While avid stargazers in North America looked up to watch the spectacle, the best vantage point was several hundred miles above the North Pole.

The Hinode spacecraft was in the right place at the ...

DURHAM, N.C. -- Many marine animals are world travelers, and scientists who study and track them can rarely predict through which nations' territorial waters their paths will lead.

In a new paper in the journal Marine Policy, Duke University Marine Lab researchers argue that coastal nations along these migratory routes do not have precedent under the law of the sea to require scientists to seek advance permission to remotely track tagged animals in territorial waters.

Requiring scientists to gain advance consent to track these animals' unpredictable movements is impossible, ...

DURHAM, N.C. – Frogs are well-known for being among the loudest amphibians, but new research indicates that the development of this trait followed another: bright coloration. Scientists have found that the telltale colors of some poisonous frog species established them as an unappetizing option for would-be predators before the frogs evolved their elaborate songs. As a result, these initial warning signals allowed different species to diversify their calls over time.

Zoologists at the National Evolutionary Synthesis Center (NESCent), the University of British Columbia, ...

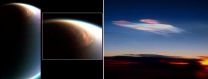

NASA scientists have identified an unexpected high-altitude methane ice cloud on Saturn's moon Titan that is similar to exotic clouds found far above Earth's poles.

This lofty cloud, imaged by NASA's Cassini spacecraft, was part of the winter cap of condensation over Titan's north pole. Now, eight years after spotting this mysterious bit of atmospheric fluff, researchers have determined that it contains methane ice, which produces a much denser cloud than the ethane ice previously identified there.

"The idea that methane clouds could form this high on Titan is completely ...

In a study just published in the International Journal of Cardiology, researchers from the K.G. Jebsen Center for Exercise in Medicine – Cardiac Exercise Research Group (CERG) at the Norwegian University of Science and Technology (NTNU) and the Department of Cardiothoracic Surgery at the St. Olavs Hospital in Trondheim, Norway have shown that shutting off the blood supply to an arm or leg before cardiac surgery protects the heart during the operation.

The research group wanted to see how the muscle of the left chamber of the heart was affected by a technique, called ...

Endurance athletes taking part in triathlons are at risk of the potentially life-threatening condition of swimming-induced pulmonary oedema. Cardiologists from Musgrove Park Hospital, Taunton, writing in the Journal of the Royal Society of Medicine, say the condition, which causes an excess collection of watery fluid in the lungs, is likely to become more common with the increase in participation in endurance sports. Increasing numbers of cases are being reported in community triathletes and army trainees. Episodes are more likely to occur in highly fit individuals undertaking ...

Six Case Western Reserve scientists are part of an international team that has discovered two compounds that show promise in decreasing inflammation associated with diseases such as ulcerative colitis, arthritis and multiple sclerosis. The compounds, dubbed OD36 and OD38, specifically appear to curtail inflammation-triggering signals from RIPK2 (serine/threonine/tyrosine kinase 2). RIPK2 is an enzyme that activates high-energy molecules to prompt the immune system to respond with inflammation. The findings of this research appear in the Journal of Biological Chemistry.

"This ...

Newly published findings from the University of Waterloo are giving women with bad backs renewed hope for better sex lives. The findings—part of the first-ever study to document how the spine moves during sex—outline which sex positions are best for women suffering from different types of low-back pain. The new recommendations follow on the heels of comparable guidelines for men released last month.

Published in European Spine Journal, the female findings debunk the popular belief that spooning—where couples lie on their sides curled in the same direction—is ...