(Press-News.org) DURHAM, N.C. -- Many marine animals are world travelers, and scientists who study and track them can rarely predict through which nations' territorial waters their paths will lead.

In a new paper in the journal Marine Policy, Duke University Marine Lab researchers argue that coastal nations along these migratory routes do not have precedent under the law of the sea to require scientists to seek advance permission to remotely track tagged animals in territorial waters.

Requiring scientists to gain advance consent to track these animals' unpredictable movements is impossible, the Duke scholars say. More importantly, it undermines the goals of the law, which are meant to encourage scientific research for conservation of marine animals.

Their paper aims to establish the legality of using various tagging technologies known as bio-logging to track migratory marine animals under an international law that was written before these technologies were widely used.

The United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea, or UNCLOS, requires in some circumstances that researchers obtain consent from coastal nations to conduct research within 200 nautical miles of their shores. The authors argue that this rule was established for research conducted from boat or aircraft, and makes little sense for research using tagged animals that swim or fly into that range.

Tracking animals through bio-logging techniques allows researchers to learn about the movement, behavior and abundance of a variety of marine animals including turtles, fish, mammals and birds. This knowledge is essential to marine animal conservation, an important goal of the UNCLOS, said David Johnston, assistant professor of the practice of marine conservation ecology at Duke. Johnston uses bio-logging in research that supports the conservation of marine vertebrates nationally and internationally.

The power of bio-logging stems from its ability to collect data remotely, but it provides no certainty about where animals will actually go. "It's essentially unknowable where tagged animals are going to go before you start tracking them," said Johnston. "You put tags on turtles in a single location in the Indian Ocean and one swims to South Africa while the other swims to Yemen. How would you predict that?"

Even if it were possible to predict where the tagged animals would go, waiting for consent from some coastal nations before collecting data in their waters via tagging would take too long, said Johnston. "A researcher could spend years trying to gain consent from some nations. And we would lose the moment -- we would lose our ability to do some really important things. And one of the most important things under the law of the sea is to work toward conserving marine resources."

The authors argue that, under UNCLOS, nations have the right to regulate traditional marine scientific research in their coastal waters, but research using bio-logging techniques can be regulated only by the nation with jurisdiction over the water where the tagging occurs. Nations whose water the animal traverses after being tagged do not enjoy this right, they said.

James Kraska, the Mary Derrickson McCurdy Visiting Scholar at the Duke University Marine Lab and an expert on the international law of the sea, said he hopes this paper will instill confidence in researchers who use bio-logging technologies and provide guidance for policy makers.

The goal, said Kraska, lead author of the paper, is to serve as reference point for dealing with any conflicts that may arise between researchers and coastal nations. "Regulators can see that people have thought about this, that we understand what the logistical issues are, what the legalities are, and that any attempts to restrict bio-logging through new interpretations of the law of the sea run counter to its overarching goals."

INFORMATION:

Funding for the study came from the Mary Derrickson McCurdy Visiting Scholar program and Duke University Marine Laboratory.

Guillermo Ortuño Crespo, who as an undergraduate studied under Kraska and Johnston at the Marine Lab, co-authored the study, which is accessible on the Web at http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0308597X14002322.

Citation: "Bio-logging of Marine Migratory Species in the Law of the Sea," James Kraska, Guillermo Ortuño Crespo, and David W. Johnston, published Oct. 23, 2014, in Marine Policy. DOI: 10.1016/j.marpol.2014.08.016

DURHAM, N.C. – Frogs are well-known for being among the loudest amphibians, but new research indicates that the development of this trait followed another: bright coloration. Scientists have found that the telltale colors of some poisonous frog species established them as an unappetizing option for would-be predators before the frogs evolved their elaborate songs. As a result, these initial warning signals allowed different species to diversify their calls over time.

Zoologists at the National Evolutionary Synthesis Center (NESCent), the University of British Columbia, ...

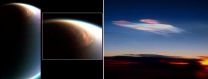

NASA scientists have identified an unexpected high-altitude methane ice cloud on Saturn's moon Titan that is similar to exotic clouds found far above Earth's poles.

This lofty cloud, imaged by NASA's Cassini spacecraft, was part of the winter cap of condensation over Titan's north pole. Now, eight years after spotting this mysterious bit of atmospheric fluff, researchers have determined that it contains methane ice, which produces a much denser cloud than the ethane ice previously identified there.

"The idea that methane clouds could form this high on Titan is completely ...

In a study just published in the International Journal of Cardiology, researchers from the K.G. Jebsen Center for Exercise in Medicine – Cardiac Exercise Research Group (CERG) at the Norwegian University of Science and Technology (NTNU) and the Department of Cardiothoracic Surgery at the St. Olavs Hospital in Trondheim, Norway have shown that shutting off the blood supply to an arm or leg before cardiac surgery protects the heart during the operation.

The research group wanted to see how the muscle of the left chamber of the heart was affected by a technique, called ...

Endurance athletes taking part in triathlons are at risk of the potentially life-threatening condition of swimming-induced pulmonary oedema. Cardiologists from Musgrove Park Hospital, Taunton, writing in the Journal of the Royal Society of Medicine, say the condition, which causes an excess collection of watery fluid in the lungs, is likely to become more common with the increase in participation in endurance sports. Increasing numbers of cases are being reported in community triathletes and army trainees. Episodes are more likely to occur in highly fit individuals undertaking ...

Six Case Western Reserve scientists are part of an international team that has discovered two compounds that show promise in decreasing inflammation associated with diseases such as ulcerative colitis, arthritis and multiple sclerosis. The compounds, dubbed OD36 and OD38, specifically appear to curtail inflammation-triggering signals from RIPK2 (serine/threonine/tyrosine kinase 2). RIPK2 is an enzyme that activates high-energy molecules to prompt the immune system to respond with inflammation. The findings of this research appear in the Journal of Biological Chemistry.

"This ...

Newly published findings from the University of Waterloo are giving women with bad backs renewed hope for better sex lives. The findings—part of the first-ever study to document how the spine moves during sex—outline which sex positions are best for women suffering from different types of low-back pain. The new recommendations follow on the heels of comparable guidelines for men released last month.

Published in European Spine Journal, the female findings debunk the popular belief that spooning—where couples lie on their sides curled in the same direction—is ...

Down syndrome is the most common chromosomal abnormality in humans, involving a third copy of all or part of chromosome 21. In addition to intellectual disability, individuals with Down syndrome have a high risk of congenital heart defects. However, not all people with Down syndrome have them – about half have structurally normal hearts.

Geneticists have been learning about the causes of congenital heart defects by studying people with Down syndrome. The high risk for congenital heart defects in this group provides a tool to identify changes in genes, both on and ...

In early drug discovery, you need a starting point, says Northeastern University associate professor of chemistry and chemical biology Michael Pollastri.

In a new research paper published Thursday in the journal PLOS Neglected Tropical Diseases, Pollastri and his colleagues present hundreds of such starting points for potentially treating African sleeping sickness, a deadly disease that claims thousands of lives annually.

Pollastri, who runs Northeastern's Laboratory for Neglected Disease Drug Discovery, ...

WASHINGTON – October 24, 2014 – Policy options for climate change risk management are straightforward and have well understood strengths and weaknesses, according to a new study by the American Meteorological Society (AMS) Policy Program.

"Large gaps remain in society's consideration of climate policy," said Paul Higgins, the author of the study. "This study can help in the development of a comprehensive strategy for climate change risk management because it explores a much larger set of policy options."

The study identifies four categories of climate ...

Washington, D.C., October 24, 2014 -- Only 6 percent of U.S. hospitals are well-prepared to receive a patient with the Ebola virus, according to a survey of infection prevention experts at U.S. hospitals conducted October 10-15 by the Association for Professionals in Infection Control and Epidemiology (APIC).

The survey asked APIC's infection preventionist members, "How prepared is your facility to receive a patient with the Ebola virus?" Of the 1,039 U.S.-based respondents working in acute care hospitals, about 6 percent reported their facility was well-prepared, while ...