(Press-News.org) NEW YORK, NY (October 26, 2014)—Dietary cocoa flavanols—naturally occurring bioactives found in cocoa—reversed age-related memory decline in healthy older adults, according to a study led by Columbia University Medical Center (CUMC) scientists. The study, published today in the advance online issue of Nature Neuroscience, provides the first direct evidence that one component of age-related memory decline in humans is caused by changes in a specific region of the brain and that this form of memory decline can be improved by a dietary intervention.

As people age, they typically show some decline in cognitive abilities, including learning and remembering such things as the names of new acquaintances or where one parked the car or placed one's keys. This normal age-related memory decline starts in early adulthood but usually does not have any noticeable impact on quality of life until people reach their fifties or sixties. Age-related memory decline is different from the often-devastating memory impairment that occurs with Alzheimer's, in which a disease process damages and destroys neurons in various parts of the brain, including the memory circuits.

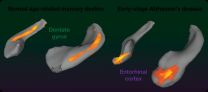

Previous work, including by the laboratory of senior author Scott A. Small, MD, had shown that changes in a specific part of the brain—the dentate gyrus—are associated with age-related memory decline. Until now, however, the evidence in humans showed only a correlational link, not a causal one. To see if the dentate gyrus is the source of age-related memory decline in humans, Dr. Small and his colleagues tested whether compounds called cocoa flavanols can improve the function of this brain region and improve memory. Flavanols extracted from cocoa beans had previously been found to improve neuronal connections in the dentate gyrus of mice.

Dr. Small is the Boris and Rose Katz Professor of Neurology (in the Taub Institute for Research on Alzheimer's Disease and the Aging Brain, the Sergievsky Center, and the Departments of Radiology and Psychiatry) and director of the Alzheimer's Disease Research Center in the Taub Institute at CUMC.

A cocoa flavanol-containing test drink prepared specifically for research purposes was produced by the food company Mars, Incorporated, which also partly supported the research, using a proprietary process to extract flavanols from cocoa beans. Most methods of processing cocoa remove many of the flavanols found in the raw plant.

In the CUMC study, 37 healthy volunteers, ages 50 to 69, were randomized to receive either a high-flavanol diet (900 mg of flavanols a day) or a low-flavanol diet (10 mg of flavanols a day) for three months. Brain imaging and memory tests were administered to each participant before and after the study. The brain imaging measured blood volume in the dentate gyrus, a measure of metabolism, and the memory test involved a 20-minute pattern-recognition exercise designed to evaluate a type of memory controlled by the dentate gyrus.

"When we imaged our research subjects' brains, we found noticeable improvements in the function of the dentate gyrus in those who consumed the high-cocoa-flavanol drink," said

lead author Adam M. Brickman, PhD, associate professor of neuropsychology at the Taub Institute.

The high-flavanol group also performed significantly better on the memory test. "If a participant had the memory of a typical 60-year-old at the beginning of the study, after three months that person on average had the memory of a typical 30- or 40-year-old," said Dr. Small. He cautioned, however, that the findings need to be replicated in a larger study—which he and his team plan to do.

Flavanols are also found naturally in tea leaves and in certain fruits and vegetables, but the overall amounts, as well as the specific forms and mixtures, vary widely.

The precise formulation used in the CUMC study has also been shown to improve cardiovascular health. Brigham and Women's Hospital in Boston recently launched an NIH-funded study of 18,000 men and women to see whether flavanols can help prevent heart attacks and strokes.

The researchers point out that the product used in the study is not the same as chocolate, and they caution against an increase in chocolate consumption in an attempt to gain this effect.

Two innovations by the investigators made the study possible. One was a new information-processing tool that allows the imaging data to be presented in a single, three-dimensional snapshot, rather than in numerous individual slices. The tool was developed in Dr. Small's lab by Usman A. Khan, an MD-PhD student in the lab, and Frank A. Provenzano, a biomedical engineering graduate student at Columbia. The other innovation was a modification to a classic neuropsychological test, allowing the researchers to evaluate memory function specifically localized to the dentate gyrus. The revised test was developed by Drs. Brickman and Small.

Besides flavanols, exercise has been shown in previous studies, including those of Dr. Small, to improve memory and dentate gyrus function in younger people. In the current study, the researchers were unable to assess whether exercise had an effect on memory or on dentate gyrus activity. "Since we didn't reach the intended VO2max (maximal oxygen uptake) target," said Dr. Small, "we couldn't evaluate whether exercise was beneficial in this context. This is not to saythat exercise is not beneficial for cognition. It may be that older people need more intense exercise to reach VO2max levels that have therapeutic effects."

INFORMATION:

MOUNT WILSON, Calif.–Astronomers at Georgia State University's Center for High Angular Resolution Astronomy (CHARA) have observed the expanding thermonuclear fireball from a nova that erupted last year in the constellation Delphinus with unprecedented clarity.

The observations produced the first images of a nova during the early fireball stage and revealed how the structure of the ejected material evolves as the gas expands and cools. It appears the expansion is more complicated than simple models previously predicted, scientists said. The results of these observations, ...

BOSTON –– Scientists say they have identified in about 20 percent of colorectal and endometrial cancers a genetic mutation that had been overlooked in recent large, comprehensive gene searches. With this discovery, the altered gene, called RNF43, now ranks as one of the most common mutations in the two cancer types.

Reporting in the October 26, 2014 edition of Nature Genetics, investigators from Dana-Farber Cancer Institute and the Broad Institute of MIT and Harvard said the mutated gene helps control an important cell-signaling pathway, Wnt, that has been ...

Why do we remember some things and not others? In a unique imaging study, two Northwestern University researchers have discovered how neurons in the brain might allow some experiences to be remembered while others are forgotten. It turns out, if you want to remember something about your environment, you better involve your dendrites.

Using a high-resolution, one-of-a-kind microscope, Daniel A. Dombeck and Mark E. J. Sheffield peered into the brain of a living animal and saw exactly what was happening in individual neurons called place cells as the animal navigated a virtual ...

Digoxin, a medication used in the treatment of heart failure, may be adaptable for the treatment of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS), a progressive, paralyzing disease, suggests new research at Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis.

ALS, also known as Lou Gehrig's disease, destroys the nerve cells that control muscles. This leads to loss of mobility, difficulty breathing and swallowing and eventually death. Riluzole, the sole medication approved to treat the disease, has only marginal benefits in patients.

But in a new study conducted in cell cultures ...

CHAMPAIGN, Ill. — Researchers report in the journal Nature that they have made a breakthrough in understanding how a powerful antibiotic agent is made in nature. Their discovery solves a decades-old mystery, and opens up new avenues of research into thousands of similar molecules, many of which are likely to be medically useful.

The team focused on a class of compounds that includes dozens with antibiotic properties. The most famous of these is nisin, a natural product in milk that can be synthesized in the lab and is added to foods as a preservative. Nisin has ...

Most of the concerns about climate change have focused on the amount of greenhouse gases that have been released into the atmosphere.

But in a new study published in Science, a group of Rutgers researchers have found that circulation of the ocean plays an equally important role in regulating the earth's climate.

In their study, the researchers say the major cooling of Earth and continental ice build-up in the Northern Hemisphere 2.7 million years ago coincided with a shift in the circulation of the ocean – which pulls in heat and carbon dioxide in the Atlantic ...

DENVER – A better survival outcome is associated with low blood levels of squamous cell carcinoma antigen, or absence of tumor invasion either into the space between the lungs and chest wall or into blood vessels of individuals with a peripheral squamous cell carcinoma, a type of non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC).

Lung cancer is the most common cause of cancer-related death worldwide and lung squamous cell carcinomas (SCC) account for 20-30% of all NSCLC. SCC can be classified as either central (c-SCC) or peripheral (p-SCC) depending on the primary location. While ...

VIDEO:

On Oct. 23, while North America was witnessing a partial eclipse of the sun, the Hinode spacecraft observed a 'ring of fire' or annular eclipse from its location hundreds of...

Click here for more information.

The moon passed between the Earth and the sun on Thursday, Oct. 23. While avid stargazers in North America looked up to watch the spectacle, the best vantage point was several hundred miles above the North Pole.

The Hinode spacecraft was in the right place at the ...

DURHAM, N.C. -- Many marine animals are world travelers, and scientists who study and track them can rarely predict through which nations' territorial waters their paths will lead.

In a new paper in the journal Marine Policy, Duke University Marine Lab researchers argue that coastal nations along these migratory routes do not have precedent under the law of the sea to require scientists to seek advance permission to remotely track tagged animals in territorial waters.

Requiring scientists to gain advance consent to track these animals' unpredictable movements is impossible, ...

DURHAM, N.C. – Frogs are well-known for being among the loudest amphibians, but new research indicates that the development of this trait followed another: bright coloration. Scientists have found that the telltale colors of some poisonous frog species established them as an unappetizing option for would-be predators before the frogs evolved their elaborate songs. As a result, these initial warning signals allowed different species to diversify their calls over time.

Zoologists at the National Evolutionary Synthesis Center (NESCent), the University of British Columbia, ...