(Press-News.org) (Santa Barbara, Calif.) — Architecture imitates life, at least when it comes to those spiral ramps in multistory parking garages. Stacked and connecting parallel levels, the ramps are replications of helical structures found in a ubiquitous membrane structure in the cells of the body.

Dubbed Terasaki ramps after their discoverer, they reside in an organelle called the endoplasmic reticulum (ER), a network of membranes found throughout the cell and connected to and surrounding the cell nucleus. Now, a trio of scientists, including UC Santa Barbara biological physicist Greg Huber, describe ER geometry using the language of theoretical physics. Their findings appear in print and online in the Oct. 31 issue of Physical Review Letters.

"Our work hypothesizes how the particular shape of this organelle forms, based on the interactions between Terasaki ramps," said Huber, who is deputy director of UCSB's Kavli Institute for Theoretical Physics. "A physicist would like to say there's a reason for the membrane's shape, that it's not just an accident. So by understanding better the physics responsible for the shape, one can start to think about other unsolved questions, including how its form relates to its function and, in the case of disease, to its dysfunction."

The rough ER consists of a number of more or less regular stacks of evenly spaced connected sheets, a structure that reflects its function as the shop floor of protein synthesis within a cell. Until recently, scientists assumed that the connections between adjacent sheets were like wormholes — that is, simple tubes.

Last year, however, it was discovered that these connections are formed by spiral ramps running up through the stack of sheets. According to lead author Jemal Guven of the Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México, this came as a surprise because spiral geometries had never previously been observed in biological membranes.

Attached to the membrane, ribosomes, which serve as the primary site for protein synthesis, dot the ER like cars populating a densely packed parking structure. "The ribosomes have to be a certain distance apart because otherwise they can't synthesize proteins," Huber explained.

"So how do you get as many ribosomes per unit volume as possible but not have them bump up against each other?" Huber asked. "The cell seems to have solved that problem by folding surfaces into layers that are nearly parallel to each other and allow a high density of ribosomes."

Different parts of the ER have different shapes: a network of tubes, a sphere that bounds the nucleus or a set of parallel sheets like the levels of a parking garage. The smooth ER consists of a tubular network of membranes meeting at three-way junctions. These junctions are also the location of lipid (or membrane) synthesis. As new lipids are produced within the smooth ER, they accumulate in these junctions, eventually cleaving apart the tubes meeting there.

In the rough ER, the parallel surfaces or stacks are connected by Terasaki spiral ramps. In some cases, one ramp is left-handed and the other right-handed — the parking-garage geometry — which is what Terasaki and colleagues (including Huber) found last year.

"We propose that the essential building blocks within the stack are not individual spiral ramps but a 'parking garage' organized around two gently pitched ramps, one of which is the mirror image of the other — a dipole," said Guven, who was assisted in his research by one of his students, Dulce María Valencia. "This architecture minimizes energy and is consistent with the laminar structure of the stacks but is also stable."

In physics, these helical structures, which connect one layer of the ER with the next, are called defects. That word, Huber noted, carries no negative connotation in this context. "When you look at this through the eyes of physics, there are certain mechanisms that suggest themselves almost immediately," Huber said. "The edge of an ER sheet is a region of high curvature because the sheet turns around and bends. The bend is actually the thing that's forming the helix."

The bend creates a U shape that looks like half of a tube. Huber and his colleagues applied the principles of differential geometry to this curved membrane. Pulling the halves of a tube apart creates a flat region spanning the two U-shaped halves, which then become part of a sheet.

"The geometrical idea is that one can actually get a sheet by pulling apart a network of tubes in a certain way," Huber explained. "Imagine that each of the U-shaped edges wants to bend, but when you try to connect those two U shapes together, each one is now bent. That's what the color figure is trying to show. A tube can generate a sheet if the edges come apart and they're allowed to bend in space."

According to Huber, this theoretical work provides a deeper story and richer vocabulary for discussing the shapes found in cell interiors. "One suspects that their shape is related to their function," he concluded. "In fact, scientists know that the shape of the ER can be an indicator of abnormal functions seen in certain diseases."

INFORMATION:

The heart holds its own pool of immune cells capable of helping it heal after injury, according to new research in mice at Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis.

Most of the time when the heart is injured, these beneficial immune cells are supplanted by immune cells from the bone marrow, which are spurred to converge in the heart and cause inflammation that leads to further damage. In both cases, these immune cells are called macrophages, whether they reside in the heart or arrive from the bone marrow. Although they share a name, where they originate appears ...

BOSTON — Findings published in the Archives of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation show that imperceptible vibratory stimulation applied to the soles of the feet improved balance by reducing postural sway and gait variability in elderly study participants. The vibratory stimulation is delivered by a urethane foam insole with embedded piezoelectric actuators, which generates the mechanical stimulation. The study was conducted by researchers from the Institute for Aging Research (IFAR) at Hebrew SeniorLife, Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center, the Wyss Institute for ...

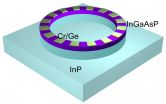

A significant breakthrough in laser technology has been reported by the U.S. Department of Energy (DOE)'s Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory (Berkeley Lab) and the University of California (UC) Berkeley. Scientists led by Xiang Zhang, a physicist with joint appointments at Berkeley Lab and UC Berkeley, have developed a unique microring laser cavity that can produce single-mode lasing even from a conventional multi-mode laser cavity. This ability to provide single-mode lasing on demand holds ramifications for a wide range of applications including optical metrology and ...

Lab-grown tissues could one day provide new treatments for injuries and damage to the joints, including articular cartilage, tendons and ligaments.

Cartilage, for example, is a hard material that caps the ends of bones and allows joints to work smoothly. UC Davis biomedical engineers, exploring ways to toughen up engineered cartilage and keep natural tissues strong outside the body, report new developments this week in the journal Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

"The problem with engineered tissue is that the mechanical properties are far from those ...

Washington, DC—The Endocrine Society today issued a Clinical Practice Guideline (CPG) for the diagnosis and treatment of acromegaly, a rare condition caused by excess growth hormone in the blood.

The CPG, entitled "Acromegaly: An Endocrine Society Clinical Practice Guideline," appeared in the November 2014 issue of the Journal of Clinical Endocrinology and Metabolism (JCEM), a publication of the Endocrine Society.

Acromegaly is usually caused by a non-cancerous tumor in the pituitary gland. The tumor manufactures too much growth hormone and spurs the body to overproduce ...

Chicago, October 30, 2014—Analysis of data from an institutional patient registry on stereotactic body radiotherapy (SBRT) indicates excellent long-term, local control, 79 percent of tumors, for medically inoperable, early stage lung cancer patients treated with SBRT from 2003 to 2012, according to research presented today at the 2014 Chicago Multidisciplinary Symposium in Thoracic Oncology. The Symposium is sponsored by the American Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO), the American Society for Radiation Oncology (ASTRO), the International Association for the Study ...

BUFFALO, N.Y. – You have to be at least 2 years old to be covered by U.S. dietary guidelines. For younger babies, no official U.S. guidance exists other than the general recommendation by national and international organizations that mothers exclusively breastfeed for at least the first six months.

So what do American babies eat?

That's the question that motivated researchers at the University at Buffalo School of Medicine and Biomedical Sciences to study the eating patterns of American infants at 6 months and 12 months old, critical ages for the development of ...

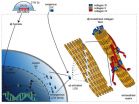

NOAA's GOES-West satellite captured an image of the birth of the Eastern Pacific Ocean's twenty-first tropical depression, located far south of Acapulco, Mexico.

NOAA's GOES-West satellite gathered infrared data on newborn Tropical Depression 21E (TD 21E) and that data was made into an image by NASA/NOAA's GOES Project at NASA's Goddard Space Flight Center in Greenbelt, Maryland. At 1200 UTC (9 a.m. EDT), the GOES-West image showed that thunderstorms circled the low-level center and extended northeast of the center indicating that southwesterly wind shear was affecting ...

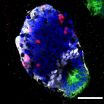

Professor Elly Tanaka and her research group at the DFG Research Center for Regenerative Therapies Dresden - Cluster of Excellence at the TU Dresden (CRTD) demonstrated for the first time the in vitro growth of a piece of spinal cord in three dimensions from mouse embryonic stem cells. Correct spatial organization of motor neurons, interneurons and dorsal interneurons along the dorsal/ventral axis was observed.

This study has been published online by the American journal "Stem Cell Reports" on 30.10.2014.

For many years Elly Tanaka and her research group have been studying ...

As transistors get smaller, they also grow less reliable. Increasing their operating voltage can help, but that means a corresponding increase in power consumption.

With information technology consuming a steadily growing fraction of the world's energy supplies, some researchers and hardware manufacturers are exploring the possibility of simply letting chips botch the occasional computation. In many popular applications — video rendering, for instance — users probably wouldn't notice the difference, and it could significantly improve energy efficiency.

At ...