(Press-News.org) Noonan syndrome is a rare disease that is characterised by a set of pathologies, including heart, facial and skeletal alterations, pulmonary stenosis, short stature, and a greater incidence of haematological problems (mainly juvenile myeloid leukaemia, or childhood leukaemia). There is an estimated incidence of 1 case for every 1,000–2,500 births, and calculations show some 20,000–40,000 people suffer from the disease in Spain. From a genetic point of view, this syndrome is associated to mutations in 11 different genes —the K-Ras gene among them— that belong to the same cell signalling pathway: RAS/MAPK. Despite mutations in the K-Ras gene not being the most frequent, 2-5% of patients, they are associated with more aggressive manifestations of the disease.

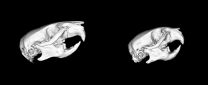

A team from the Spanish National Cancer Research Centre's (CNIO) Experimental Oncology Group has developed a mouse model that expresses the most common K-Ras mutation found in Noonan patients and reproduced its most representative features. This study has been done alongside the research groups of Xosé R. Bustelo at the Cancer Research Centre in Salamanca; Manuel Desco at the Gregorio Marañón's Healthcare Research Institute, and Christopher Heeschen at CNIO. Their conclusions have been published in PNAS (Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences).

"Given the wide variety of mutations associated with this syndrome, these animal models are important tools for investigating the physical alterations associated with each one of them," says Isabel Hernández-Porras, first author of the study. "That way these models will allow for the development of specific treatments for each mutation and for better clinical follow up of patients."

PRENATAL TREATMENT PREVENTS SYMPTOMS IN MICE

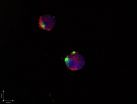

The researchers used a commercial MEK inhibitor in a preventive treatment; the inhibitor was applied to mice with a genetic alteration in K-Ras from the embryonic stage until weaning.

"We saw that all of the developmental alterations disappeared: at the end of the treatment, the heart, facial features and size of the mouse were normal," says Hernández-Porras. "Leukaemia, however, which usually manifests in about 10% of Noonan patients, was still present. We think there might be other pathways that influence its appearance and development".

The study is fundamental for broadening current knowledge about the syndrome and opening up possibilities for the development of treatments. "We have seen, as with other research groups, that the seriousness or intensity of each of the alterations is related not only to the mutation the syndrome is attributed to [in this case the K-Ras gene] but also to changes in the rest of the genome," says Hernández-Porras, who concludes that: "These mouse models will allow us to determine which modifications have a beneficial or harmful effect on this syndrome and to design potential therapeutic targets."

Alberto J. Schuhmacher, a researcher who took part in the study, says: "In the next few years, diagnostic prenatal testing could be performed, similar to the screening test used for Down's syndrome; sequencing the genome of the foetus by analysing cells extracted from the amniotic fluid or foetal DNA from the mother's blood. Once these mouse models have helped us advance our knowledge of these illnesses and develop more precise drugs, we might be able to treat embryo defects without endangering the health of the mother or the foetus."

This model also confirms that different mutations give rise to syndromes that are similar in appearance, so researchers warn of the need to stop classifying them as a function of the observed physical features, which at times leads to wrong diagnoses. "We need to classify them based on genetic sequencing, so that in the future each patient can receive the most appropriate treatment," says Schuhmacher.

INFORMATION:

This study was funded by the Ramón Areces Foundation, the European Research Council and the National Institute of Health Carlos III (FIS).

Reference article:

K-RasV14I recapitulates Noonan syndrome in mice. http://www.pnas.org/cgi/doi/10.1073/pnas.1418126111

PATIENTS with a specific type of oesophageal cancer survived longer when they were given the latest lung cancer drug, according to trial results being presented at the National Cancer Research Institute (NCRI) Cancer Conference today (Wednesday).

Up to one in six patients with oesophageal cancer were found to have EGFR duplication in their tumour cells and taking the drug gefitinib, which targets this fault, boosted their survival by up to six months, and sometimes beyond.

This is the first treatment for advanced oesophageal cancer shown to improve survival in patients ...

Fatih Uckun, Jianjun Cheng and their colleagues have taken the first steps towards developing a so-called "smart bomb" to attack the most common and deadly form of childhood cancer — called B-lineage acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL).

In a November study in the new peer-reviewed, open-access journal EBioMedicine, they describe how this approach could eventually prove lifesaving for children who have relapsed after initial chemotherapy and face a less than 20 percent chance of long-term survival.

"We knew that we could kill chemotherapy-resistant leukemia cells ...

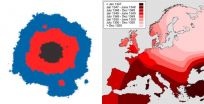

The current Ebola outbreak shows how quickly diseases can spread with global jet travel.

Yet, knowing how to predict the spread of these epidemics is still uncertain, because the complicated models used are not fully understood, says a University of California, Berkeley biophysicist.

Using a very simple model of disease spread, Oskar Hallatschek, assistant professor of physics, proved that one common assumption is actually wrong. Most models have taken for granted that if disease vectors, such as humans, have any chance of "jumping" outside the initial outbreak area ...

Researchers using a new type of tracking device on female elephant seals have discovered that adding body fat helps the seals dive more efficiently by changing their buoyancy.

The study, published November 5 in the Proceedings of the Royal Society B, looked at the swimming efficiency of elephant seals during their feeding dives and how that changed in the course of months-long migrations at sea as the seals put on more fat. The results showed that when elephant seals are neutrally buoyant--meaning they don't float up or sink down in the water--they spend less energy ...

A University of Oregon researcher wants those "R" words to resonate among young athletes. They are key terms used in an online educational tool designed to teach coaches, educators, teens and parents about concussions.

Brain 101: The Concussion Playbook successfully increased knowledge and attitudes related to brain injuries among students and parents in a study that compared its use in 12 high schools with the usual care practices of 13 other high schools during the fall 2011 sports season. The findings are online ahead of print in the Journal of Adolescent Health.

Participants, ...

A study led by a researcher from Plymouth University in the UK, has discovered that the inhibition of a particular mitochondrial fission protein could hold the key to potential treatment for Parkinson's Disease (PD).

The findings of the research are published today, 5th November 2014, in Nature Communications.

PD is a progressive neurological condition that affects movement. At present there is no cure and little understanding of why some people get the condition. In the UK one on 500 people, around 127,000, have PD.

The debilitating movement symptoms of the disease ...

ANN ARBOR, Mich. — Millions of people with diabetes take medicine to ease the shooting, burning nerve pain that their disease can cause. And new research suggests that no matter which medicine their doctor prescribes, they'll get relief.

But some of those medicines cost nearly 10 times as much as others, apparently with no major differences in how well they ease pain, say a pair of University of Michigan Medical School experts in a new commentary in the Annals of Internal Medicine.

That makes cost -- not effect -- a crucial factor in deciding which medicine ...

TALLAHASSEE, Fla. — A new study by a Florida State University researcher reveals that a new dietary supplement is superior to calcium and vitamin D when it comes to bone health.

Over 12 months, Bahram H. Arjmandi, Margaret A. Sitton Professor in the Department of Nutrition, Food and Exercise Sciences and Director of the Center for Advancing Exercise and Nutrition Research on Aging (CAENRA) at Florida State, studied the impact of the dietary supplement KoACT® versus calcium and vitamin D on bone loss. KoACT is a calcium-collagen chelate, a compound containing ...

A child's ability to distinguish musical rhythm is related to his or her capacity for understanding grammar, according to a recent study from a researcher at the Vanderbilt Kennedy Center.

Reyna Gordon, Ph.D., a research fellow in the Department of Otolaryngology and at the Vanderbilt Kennedy Center, is the lead author of the study that was published online recently in the journal Developmental Science. She notes that the study is the first of its kind to show an association between musical rhythm and grammar.

Though Gordon emphasizes that more research will be necessary ...

VTT Technical Research Centre of Finland has developed an innovative magnetometer that can replace conventional technology in applications such as neuroimaging, mineral exploration and molecular diagnostics. Its manufacturing costs are between 70 and 80 per cent lower than those of traditional technology, and the device is not as sensitive to external magnetic fields as its predecessors. The design of the magnetometer also makes it easier to integrate into measuring systems.

Magnetometers are sensors that measure magnetic fields or changes in magnetic fields. The kinetic ...