(Press-News.org) Scientists from the Department of Energy's SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory and the University of California, Los Angeles have shown that a promising technique for accelerating electrons on waves of plasma is efficient enough to power a new generation of shorter, more economical accelerators. This could greatly expand their use in areas such as medicine, national security, industry and high-energy physics research.

This achievement is a milestone in demonstrating the practicality of plasma wakefield acceleration, a technique in which electrons gain energy by essentially surfing on a wave of electrons within an ionized gas.

Using SLAC's Facility for Advanced Accelerator Experimental Tests (FACET), a DOE Office of Science User Facility, the researchers boosted bunches of electrons to energies 400 to 500 times higher than they could reach traveling the same distance in a conventional accelerator. Just as important, energy was transferred to the electrons much more efficiently than in previous experiments. This crucial combination of energy and efficiency had never been reached before. The results are described in a paper published today in the journal Nature.

"Many of the practical aspects of an accelerator are determined by how quickly the particles can be accelerated," said SLAC accelerator physicist Mike Litos, lead author of the paper. "To put these results in context, we have now shown that we could use this technique to accelerate an electron beam to the same energies achieved in the 2-mile-long SLAC linear accelerator in less than 20 feet."

Plasma wakefields have been of interest to accelerator physicists for 35 years as one of the more promising ways to drive the smaller, cheaper accelerators of the future. The UCLA and SLAC groups have been at the forefront of research on plasma wakefield acceleration for more than a decade. In a 2007 paper, researchers announced they'd accelerated electrons in the tail end of a long electron bunch from 42 billion electronvolts to 85 billion electronvolts, causing a great deal of excitement in the scientific community. However, fewer than 1 billion of the 18 billion electrons in the pulse actually gained energy and they had a wide spread of energies, making them unsuitable for experiments.

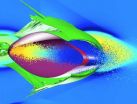

In this experiment, researchers sent pairs of electron bunches containing 5 billion to 6 billion electrons each into a laser-generated column of plasma inside an oven of hot lithium gas. The first bunch in each pair was the drive bunch; it blasted all the free electrons away from the lithium atoms, leaving the positively charged lithium nuclei behind – a configuration known as the "blowout regime." The blasted electrons then fell back in behind the second bunch of electrons, known as the trailing bunch, forming a "plasma wake" that propelled the trailing bunch to higher energy.

Previous experiments had demonstrated multi-bunch acceleration, but the team at SLAC was the first to reach the high energies of the blowout regime, where maximum energy gains at maximum efficiencies can be found. Of equal importance, the accelerated electrons wound up with a relatively small energy spread.

"These results have an additional significance beyond a successful experiment," said Mark Hogan, SLAC accelerator physicist and one of the principal investigators of the experiment. "Reaching the blowout regime with a two-bunch configuration has enabled us to increase the acceleration efficiency to a maximum of 50 percent – high enough to really show that plasma wakefield acceleration is a viable technology for future accelerators."

The plasma source used in the experiment was developed by a team of scientists led by Chandrashekhar Joshi, director of the Neptune Facility for Advanced Accelerator Research at UCLA. He is the UCLA principal investigator for this research, a faculty member with the UCLA Henry Samueli School of Engineering and Applied Science, and a long-time collaborator with the SLAC group.

"It is gratifying to see that the UCLA-SLAC collaboration on plasma wakefield acceleration continues to solve seemingly intractable problems one by one through systematic experimental work," Joshi said. "It is this kind of transformative research that attracts the best and the brightest students to this field, and it is imperative that they have facilities such as FACET to carry it out."

There are more milestones ahead. Before plasma wakefield acceleration can be put to use, Hogan said, the trailing bunches must be shaped and spaced just right so all the electrons in a bunch receive exactly the same boost in energy, while maintaining the high overall quality of the electron beam.

"We have our work cut out for us," Hogan said. "But you don't get many chances to conduct research that you know in advance has the potential to be immensely rewarding, both scientifically and practically."

INFORMATION:

Computer simulations used in the experiments were developed by Warren Mori's group at UCLA. Additional contributors included researchers from SLAC, the University of Oslo in Norway, Tsinghua University in China and Max Planck Institute for Physics in Germany. The research was funded by the DOE Office of Science.

SLAC is a multi-program laboratory exploring frontier questions in photon science, astrophysics, particle physics and accelerator research. Located in Menlo Park, Calif., SLAC is operated by Stanford University for the U.S. Department of Energy's Office of Science.

SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory is supported by the Office of Science of the U.S. Department of Energy. The Office of Science is the single largest supporter of basic research in the physical sciences in the United States, and is working to address some of the most pressing challenges of our time. For more information, please visit science.energy.gov.

Researchers hit milestone in accelerating particles with plasma

SLAC demonstration shows technique is powerful, efficient enough to drive future particle accelerators

2014-11-05

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

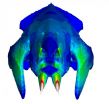

Madagascar: Fossil skull analysis offers clue to mammals' evolution

2014-11-05

AMHERST, Mass. – The surprise discovery of the fossilized skull of a 66- to 70-million-year-old, groundhog-like creature on Madagascar has led to new analyses of the lifestyle of the largest known mammal of its time by a team of specialists including biologist Elizabeth Dumont at the University of Massachusetts Amherst, an expert in jaw structure and bite mechanics.

The skull of this animal, named Vintana sertichi, was found in a geological formation deposited when a great variety of dinosaurs roamed the earth. With a skull that is almost five inches (125 mm) ...

New global wildfire analysis indicates humans need to coexist and adapt

2014-11-05

A new study led by the University of California, Berkeley and involving the University of Colorado Boulder indicates the current response to wildfires around the world—aggressively fighting them—is not making society less vulnerable to such events.

The study suggests the key is to treat fires like other natural hazards—including earthquakes, severe storms and flooding—by learning to coexist, adapt and identify vulnerabilities. The new study indicates government-sponsored firefighting and land management policies may actually encourage development ...

Bone drug should be seen in a new light for its anti-cancer properties

2014-11-05

Australian researchers have shown why calcium-binding drugs commonly used to treat people with osteoporosis, or with late-stage cancers that have spread to bone, may also benefit patients with tumours outside the skeleton, including breast cancer.

Several clinical trials – where women with breast cancer were given these drugs (bisphosphonates) alongside normal treatment for early-stage disease – showed that they can confer a 'survival advantage' and inhibit cancer spread in some women, although until now no-one has understood why.

A new study by Professor ...

Clearing a path for electrons in polymers: Closing in on the speed limits

2014-11-05

Researchers from the University of Cambridge have identified a class of low-cost, easily-processed semiconducting polymers which, despite their seemingly disorganised internal structure, can transport electrons as efficiently as expensive crystalline inorganic semiconductors.

In this new polymer, about 70% of the electrons are free to travel, whereas in conventional polymers that number can be less than 50%. The materials approach intrinsic disorder-free limits, which would enable faster, more efficient flexible electronics and displays. The results are published today ...

Sustainable co-existence with wildfire recognizes ecological benefits, human needs

2014-11-05

CHICAGO (November 5, 2014) – When wildfire and people intersect, it is often in the wildland-urban interface, or WUI, a geography where homes, roads and trails intermix with fire-prone vegetation. In an article published Thursday in the journal Nature, U.S. Forest Service scientist Sarah McCaffrey and her colleagues advocate for an approach to wildfire management that reflects ecological science as well as research on the human dimensions of wildfire and fire management.

"Learning to Coexist with Wildfire," a research review led by the University of California-Berkley, ...

Readmission rates above average for survivors of septic shock, Penn study finds

2014-11-05

PHILADELPHIA –A diagnosis of septic shock was once a near death sentence. At best, survivors suffered a substantially reduced quality of life.

Penn Medicine researchers have now shown that while most patients now survive a hospital stay for septic shock, 23 percent will return to the hospital within 30 days, many with another life-threatening condition -- a rate substantially higher than the normal readmission rate at a large academic medical center. The findings are published in the new issue of Critical Care Medicine.

"Half of patients diagnosed with sepsis ...

High rate of insomnia during early recovery from addiction

2014-11-05

November 5, 2014 – Insomnia is a "prevalent and persistent" problem for patients in the early phases of recovery from the disease of addiction—and may lead to an increased risk of relapse, according to a report in the November/December Journal of Addiction Medicine, the official journal of the American Society of Addiction Medicine. The journal is published by Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, a part of Wolters Kluwer Health.

"Treating sleep disturbance in early recovery may have considerable impact on maintenance of sobriety and quality of life," according ...

Betting on brain research

2014-11-05

Despite great advances in understanding how the human brain works, psychiatric conditions, neurodegenerative disorders, and brain injuries are on the rise. Progress in the development of new diagnostic and treatment approaches appears to have stalled. In a special issue of the Cell Press journal Neuron, experts look at the challenges associated with "translational neuroscience," or efforts to bring advances in the lab to the patients who need them.

"A variety of global impact studies have identified brain disorders as a leading contributor to disabilities and morbidity ...

Risk stratification model may aid in lung cancer staging and treatment decisions

2014-11-05

DENVER – A risk stratification model based on lymph node characteristics confirms with a high level of confidence the true lack of lung cancer in lymph nodes adequately sampled with endobronchial ultrasound-guided transbronchial needle aspiration and classified as negative.

Lung cancer treatment and prognosis is critically dependent on accurate staging that takes into account the extent to which cancer has spread from the primary lung tumor to other locations. Examination of lymph nodes containing lung cancer cells that have spread can be done by surgical removal, ...

Retinal-scan analysis can predict advance of macular degeneration, Stanford study finds

2014-11-05

Stanford University School of Medicine scientists have found a new way to forecast which patients with age-related macular degeneration are likely to suffer from the most debilitating form of the disease.

The new method predicts, on a personalized basis, which patients' AMD would, if untreated, probably make them blind, and roughly when this would occur. Simply by crunching imaging data that is already commonly collected in eye doctors' offices, ophthalmologists could make smarter decisions about when to schedule an individual patient's next office visit in order to optimize ...

LAST 30 PRESS RELEASES:

Increased risk of bullying in open-plan offices

Frequent scrolling affects perceptions of the work environment

Brain activity reveals how well we mentally size up others

Taiwanese and UK scientists identify FOXJ3 gene linked to drug-resistant focal epilepsy

Pregnancy complications impact women’s stress levels and cardiovascular risk long after delivery

Spring fatigue cannot be empirically proven

Do prostate cancer drugs interact with certain anticoagulants to increase bleeding and clotting risks?

Many patients want to talk about their faith. Neurologists often don't know how.

AI disclosure labels may do more harm than good

The ultra-high-energy neutrino may have begun its journey in blazars

Doubling of new prescriptions for ADHD medications among adults since start of COVID-19 pandemic

“Peculiar” ancient ancestor of the crocodile started life on four legs in adolescence before it began walking on two

AI can predict risk of serious heart disease from mammograms

New ultra-low-cost technique could slash the price of soft robotics

Increased connectivity in early Alzheimer’s is lowered by cancer drug in the lab

Study highlights stroke risk linked to recreational drugs, including among young users

Modeling brain aging and resilience over the lifespan reveals new individual factors

ESC launches guidelines for patients to empower women with cardiovascular disease to make informed pregnancy health decisions

Towards tailor-made heat expansion-free materials for precision technology

New research delves into the potential for AI to improve radiology workflows and healthcare delivery

Rice selected to lead US Space Force Strategic Technology Institute 4

A new clue to how the body detects physical force

Climate projections warn 20% of Colombia’s cocoa-growing areas could be lost by 2050, but adaptation options remain

New poll: American Heart Association most trusted public health source after personal physician

New ethanol-assisted catalyst design dramatically improves low-temperature nitrogen oxide removal

New review highlights overlooked role of soil erosion in the global nitrogen cycle

Biochar type shapes how water moves through phosphorus rich vegetable soils

Why does the body deem some foods safe and others unsafe?

Report examines cancer care access for Native patients

New book examines how COVID-19 crisis entrenched inequality for women around the world

[Press-News.org] Researchers hit milestone in accelerating particles with plasmaSLAC demonstration shows technique is powerful, efficient enough to drive future particle accelerators