(Press-News.org) Women born with a rare condition that gives them a Y chromosome don't only look like women physically, they also have the same brain responses to visual sexual stimuli, a new study shows.

The journal Hormones and Behavior published the results of the first brain imaging study of women with complete androgen insensitivity, or CAIS, led by psychologists at Emory.

"Our findings clearly rule out a direct effect of the Y chromosome in producing masculine patterns of response," says Kim Wallen, an Emory professor of psychology and behavioral neuroendocrinology. "It's further evidence that we need to revamp our thinking about what we mean by 'man' and 'woman.'"

Wallen conducted the research with Stephan Hamann, Emory professor of psychology, and graduate students in their labs. Researchers from Pennsylvania State University and Indiana University also contributed to the study.

The Y chromosome was identified as the sex-determining chromosome in 1905. Females normally have an XX chromosome pair and males have an XY chromosome pair.

By the 1920s, biochemists also began intensively studying androgens and estrogens, chemical substances commonly referred to as "sex hormones." During pregnancy, the presence of a Y chromosome leads the fetus to produce testes. The testes then secrete androgens that stimulate the formation of a penis, scrotum and other male characteristics.

Women with CAIS are born with an XY chromosome pair. Because of the Y chromosome, the women have testes that remain hidden within their groins but they lack neural receptors for androgens so they cannot respond to the androgens that their testes produce. They can, however, respond to the estrogens that their testes produce so they develop physically as women and undergo a feminizing puberty. Since they do not have ovaries or a uterus and do not menstruate they cannot have children.

"Women with CAIS have androgen floating around in their brains but no receptors for it to connect to," Wallen says. "Essentially, they have this default female pattern and it's as though they were never exposed to androgen at all."

Wallen and Hamann are focused on teasing out neural differences between men and women. In a 2004 study, they used functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) to study the neural activity of typical men and typical women while they were viewing photos of people engaged in sexual activity.

The patterns were distinctively clear, Hamann says. "Men showed a lot more activity than women in two areas of the brain – the amygdala, which is involved in emotion and motivation, and the hypothalamus which is involved in regulations of hormones and possibly sexual behavior."

For the most recent study, the researchers repeated the experiment while also including 13 women with CAIS in addition to women without CAIS and men.

"We didn't find any difference between the neural responses of women with CAIS and typical women, although they were both very different from those of the men in the study," Hamann says. "This result supports the theory that androgen is the key to a masculine response. And it further confirms that women with CAIS are typical women psychologically, as well as their physical phenotype, despite having a Y chromosome."

A limitation of the study is that it did not measure environmental effects on women with CAIS. "These women look the same as other women," Wallen explains. "They're reared as girls and they're treated as girls, so their whole developmental experience is feminized. We can't rule out that experience as a factor in their brain responses."

The findings may have broader applications in cognition and health. "Anything that we can learn about sex differences in the brain," Wallen says, "may help answer important questions such as why autism is more common in males and depression more common in females."

INFORMATION: END

Having a Y chromosome doesn't affect women's response to sexual images, brain study shows

2014-11-05

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

Mosquitofish genitalia change rapidly due to human impacts

2014-11-05

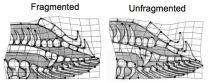

The road that connects also divides.

This dichotomy – half-century-old roads connecting portions of Bahamian islands while fragmenting the tidal waters below – leads to rapid and interesting changes in the fish living in those fragmented sections, according to a new study from North Carolina State University.

NC State Ph.D. student Justa Heinen-Kay and assistant professor of biological sciences R. Brian Langerhans show, in a paper published in the journal Evolutionary Applications, that the male genitalia of three different species of Bahamian mosquitofish ...

'Direct writing' of diamond patterns from graphite a potential technological leap

2014-11-05

WEST LAFAYETTE, Ind. – What began as research into a method to strengthen metals has led to the discovery of a new technique that uses a pulsing laser to create synthetic nanodiamond films and patterns from graphite, with potential applications from biosensors to computer chips.

"The biggest advantage is that you can selectively deposit nanodiamond on rigid surfaces without the high temperatures and pressures normally needed to produce synthetic diamond," said Gary Cheng, an associate professor of industrial engineering at Purdue University. "We do this at room temperature ...

Piglet brain atlas new tool in understanding human infant brain development

2014-11-05

URBANA, Ill. – A new online tool developed by researchers at the University of Illinois will further aid studies into postnatal brain growth in human infants based on the similarities seen in the development of the piglet brain, said Rod Johnson, a U of I professor of animal sciences.

Through a cooperative effort between researchers in animal sciences, bioengineering, and U of I's Beckman Institute, Johnson and colleagues Ryan Dilger and Brad Sutton have developed a magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) based brain atlas for the four-week old piglet that offers a three-dimensional ...

Expansion of gambling does not lead to more problem gamblers, study finds

2014-11-05

BUFFALO, N.Y. – In the past decade, online gambling has exploded and several states, including New York, have approved measures to legalize various types of gambling. So, it's only natural that the number of people with gambling problems has also increased, right?

Wrong, say researchers at the University at Buffalo Research Institute on Addictions (RIA).

"We compared results from two nationwide telephone surveys, conducted a decade apart. We found no significant increase in the rates of problem gambling in the U.S., despite a nationwide increase in gambling opportunities," ...

Financial experts may not always be so expert new Notre Dame study reveals

2014-11-05

When in doubt, an expert always knows better. Except in the case of mutual-fund managers. There may be some room for doubt in their case a new study by Andriy Bodnaruk, an assistant finance professor at the University of Notre Dame, and colleague Andrei Simonov from Michigan State University, suggests.

Bodnaruk and Simonov studied 84 mutual-fund managers in Sweden to determine how well they manage their own finances.

"We asked the question whether financial experts make better investment decisions than ordinary investors," Bodnaruk said. "We identified a group of investors ...

ADHD-air pollution link

2014-11-05

Prenatal exposure to polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons, or PAH, a component of air pollution, raises the odds of behavior problems associated with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder, or ADHD, at age 9, according to researchers at the Columbia Center for Children's Environmental Health at the Mailman School of Public Health. Results are published online in the journal PLOS ONE.

The researchers followed 233 nonsmoking pregnant women and their children in New York City from pregnancy into childhood, and found that children born to mothers exposed to high levels of PAH ...

Small New Zealand population initiated rapid forest transition c. 750 years ago

2014-11-05

Human-set fires by a small Polynesian population in New Zealand ~750 years ago may have caused fire-vulnerable forests to shift to shrub land over decades, rather than over centuries, as previously thought, according to a study published November 5, 2014 in the open-access journal PLOS ONE by David McWethy from Montana State University and colleagues.

Human impacts on forest composition and structure have been documented worldwide; however, the rate at which ancient human activities led to permanent deforestation is poorly understood. In South Island, New Zealand, the ...

Ah-choo! Expect higher grass pollen and allergen exposure in the coming century

2014-11-05

AMHERST, Mass. – Results of a new study by scientists at the University of Massachusetts Amherst strongly suggest that there will be notable increases in grass pollen production and allergen exposure up to 202 percent in the next 100 years, leading to a significant, worldwide impact on human health due to predicted rises in carbon dioxide (CO2) and ozone (O3) due to climate change.

While CO2 stimulates reproduction and growth in plants, ozone has a negative impact on plant growth, the authors point out. In this study in Timothy grass, researchers led by environmental ...

Scientists on NOAA-led mission discover new coral species off California

2014-11-05

A NOAA-led research team has discovered a new species of deep-sea coral and a nursery area for catsharks and skates in the underwater canyons located close to the Gulf of Farallones and Cordell Bank national marine sanctuaries off the Sonoma coast.

In the first intensive exploration of California's offshore areas north of Bodega Head, a consortium of federal and state marine scientists used small submersibles and other innovative technologies to investigate, film and photograph marine life that has adapted to survive in offshore waters reaching 1,000 feet deep.

The ...

A fraction of the global military spending could save the planet's biodiversity

2014-11-05

A fundamental step-change involving an increase in funding and political commitment is urgently needed to ensure that protected areas deliver their full conservation, social and economic potential, according to an article published today in Nature by experts from Wildlife Conservation Society, the University of Queensland, and the IUCN World Commission on Protected Areas (WCPA).

The paper, The performance and potential of protected areas, comes ahead of the IUCN World Parks Congress 2014 – a once-in-a-decade global forum on protected areas opening next week in ...