Researchers from MIT's Research Laboratory of Electronics, working with physicians from Harvard Medical School and the Einstein Medical Center in Philadelphia, believe that repurposing a piece of medical equipment standard in all ambulances in the United States and Europe could help paramedics make this type of field diagnosis.

In the December issue of IEEE Transactions on Biomedical Engineering, they present a new algorithm that can, with high accuracy, determine whether a patient is suffering from emphysema or heart failure based on readings from a capnograph --a machine that measures the concentration of carbon dioxide in a patient's exhalations.

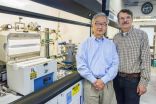

"This machine is ubiquitous," says George Verghese, the Henry Ellis Warren Professor of Electrical and Biomedical Engineering at MIT and one of the paper's coauthors. "It's actually in every emergency department and operating room. But the use that they've typically made of it is much more limited than what we were attempting here."

In the United States, capnography was first introduced in the 1980s, as a way to aid medical professionals inserting breathing tubes into the tracheas of sedated patients. If the tube were accidentally inserted into the esophagus -- which leads to the stomach, rather than the lungs -- the capnograph would measure no carbon dioxide concentrations at all.

In that context, a capnogram is easy to read. If the capnograph displays a regular wave pattern, with crests for exhalations and troughs for inhalations, the tube has been inserted properly. If the capnogram flatlines, it hasn't been.

Rich signal

But over time, physicians observed that the capnograms of patients with congestive heart failure and emphysema -- or chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, as it's known in the medical literature -- were subtly but consistently different both from each other and from those of healthy subjects.

One of those physicians, Baruch Krauss, an emergency-medicine specialist at Boston Children's Hospital and an associate professor at Harvard Medical School, thought that the capnographic signal could be a source of diagnostically useful information, particularly for paramedics. A blood test performed in a hospital lab can accurately distinguish emphysema and heart failure, but it takes about an hour from the time a sample is received -- too long for a patient who's distressed enough to call 911.

Krauss was aware that the Computational Physiology and Clinical Inference Group at RLE specialized in novel diagnostic applications of minimally invasive sensors, so he requested a meeting with the group's leaders, Verghese and assistant professor of electrical and biomedical engineering Thomas Heldt, who has since joined MIT's Institute of Medical Engineering and Science. "We didn't even know the word 'capnography' until Baruch set up a meeting with us and came and told us about it," Verghese says.

Verghese and Heldt recruited Rebecca Mieloszyk, a student in their group who had just begun her master's degree, to investigate the relationship between patients' capnograms and their ultimate diagnoses.

Mieloszyk's first task was to identify features of the capnographic signal that appeared to vary between populations. The crests of the waves in healthy subjects' capnograms seemed to plateau at a maximum concentration, for instance, while those in sick patients' didn't. Other obvious factors to consider were the duration of the exhalations and the intervals between them.

Once she had identified maybe a dozen such features, she wrote a machine-learning algorithm that would look for patterns in the features that seemed to correlate with patients' ultimate diagnoses. But that algorithm was somewhat unconventional.

Democratic decisions

Rather than training a single classifier on one set of data and then turning it loose on another set to see how it performed, she split the training data into 50 subsets. Each subset consisted of a random selection of about 70 percent of the data -- so there was significant overlap between subsets, but no two subsets were identical. Then she used those subsets to train 50 different classifiers. The algorithm's ultimate output was the result of a vote by the 50 classifiers.

Diagnostic techniques are generally assessed according to their true-positive rates -- the fraction of actual cases that they successfully diagnose -- and their false-positive rates -- the fraction of healthy subjects they classify as sick. These can be plotted against each other on a graph, with true-positive as the y-axis and false-positive as the x-axis.

The ideal diagnostic would yield a straight line across the top of the graph: Its true-positive rate is always 1, even when the false-positive rate is 0. The line produces a square with an area of 1, since its top stretches from (0,1) to (1,1). So a good diagnostic is one whose area under the curve is close to 1.

In their tests, the MIT researchers and their colleagues found that their algorithm for distinguishing healthy subjects from those with emphysema yielded an area under the curve of 0.98. The algorithm that distinguished emphysema patients from those with congestive heart failure checked in at 0.89.

"[That] is very good performance," Krauss says. "Now, when the ambulance system picks up an elderly person who's short of breath, a lot of times they can't determine whether they're short of breath from emphysema or heart failure, so they just take their best guess. So when we're talking about guesstimates, I think we really do pretty well."

INFORMATION:

Validation

To determine precisely how well, however, the researchers are currently conducting a double-blind experiment in which paramedics assess the conditions of patients while also taking capnograms, whose results are analyzed by the MIT researchers' algorithm. In other work, other members of Verghese's and Heldt's team are evaluating whether capnography can measure the severity of asthma attacks and the degree of sedation in patients undergoing medical procedures.

Written by Larry Hardesty, MIT News Office

Related links

Making sense of medical sensors

http://newsoffice.mit.edu/2013/making-sense-of-medical-sensors-0419

Sensing when the brain is under pressure

http://newsoffice.mit.edu/2012/intracranial-pressure-monitor-0411