Manipulating complex molecules by hand

New method in scanning probe microscopy: Jülich researchers create a word using 47 molecules

2014-11-06

(Press-News.org) This news release is available in German.

"The technique makes it possible for the first time to remove large organic molecules from associated structures and place them elsewhere in a controlled manner," explains Dr. Ruslan Temirov from Jülich's Peter Grünberg Institute. This brings the scientists one step closer to finding a technology that will enable single molecules to be freely assembled to form complex structures. Research groups around the world are working on a modular system like this for nanotechnology, which is considered imperative for the development of novel, next-generation electronic components.

Using motion tracking, Temirov's young investigators group coupled the movements of an operator's hand directly to the scanning probe microscope. The tip of this microscope can be used to lift molecules and re-deposit them, much like a crane. With a magnification of five hundred million to one, the relatively crude human movements are transferred to atomic dimensions. "A hand motion of five centimetres causes the sharp tip of the scanning probe microscope to move just one angstrom over the specimen. This corresponds to the typical magnitude of atomic radii and bond lengths in molecules," explains Ruslan Temirov.

Controlling the system in this way, however, requires some practice. "The first few attempts to remove a molecule took 40 minutes. Towards the end we needed only around 10 minutes," says Matthew Green. It took the PhD student four days in total to remove 47 molecules and thus stencil the word "JÜLICH" into a perylenetetracarboxylic acid dianhydride (PTCDA) monolayer. PTCDA is an organic semiconductor that plays an important role in the development of organic electronics - a field that makes it possible to print flexible components or cheap disposable chips, for example, which is inconceivable with conventional silicon technology.

Small spelling mistakes can even be corrected without difficulty using the new method. A molecule removed by mistake when creating the horizontal line in "H" was easily replaced by Green using a new molecule that he removed from the edge of the layer. "And exactly this is the advantage of this method. The experimenter can intervene in the process and find a solution if a molecule is accidentally removed or if it unexpectedly jumps back to its original position," says the physicist.

The interactive approach makes it possible to manipulate molecules that are part of large associated structures in a controlled manner. In contrast to single atoms and molecules, the manipulation of which using scanning probe microscopes has long been routine, larger molecular assemblies were almost impossible to manipulate in a targeted manner until now. The reason for this is that the bonding forces of the molecules, which are bound to all of the surrounding neighbouring molecules, are almost impossible to predict exactly. Only during the experiment it becomes clear what force is required to lift a molecule and via what path it can be successfully removed.

The experience gained will help to speed up time-consuming operations. "In future, self-learning computers will take over complex molecule manipulation. We are now gaining the intuition for nanomechanics that is so essential for this project using our novel control system and quite literally by hand," says Dr. Christian Wagner, who is also part of the Jülich group.

INFORMATION:

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

2014-11-06

New research reports that the rate of hospitalization due to hepatitis A virus (HAV) infection has significantly declined in the U.S. from 2002 to 2011. Findings published in Hepatology, a journal of the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases, show that older patients and those with chronic liver disease are most likely to be hospitalized for HAV. Vaccination of adults with chronic liver disease may prevent infection with hepatitis A and the need for hospitalization.

The World Health Organization (WHO) estimates that each year 1.4 million individuals worldwide ...

2014-11-06

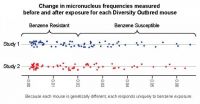

A genetically diverse mouse model is able to predict the range of response to chemical exposures that might be observed in human populations, researchers from the National Institutes of Health have found. Like humans, each Diversity Outbred mouse is genetically unique, and the extent of genetic variability among these mice is similar to the genetic variation seen among humans.

Using these mice, researchers from the National Toxicology Program (NTP), an interagency program headquartered at the National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences (NIEHS), were able to identify ...

2014-11-06

WASHINGTON, D.C., November 6, 2014--Short-term certificate programs at community colleges offer limited labor-market returns, on average, in most fields of study, according to new research published today in Educational Evaluation and Policy Analysis (EEPA), a peer-reviewed journal of the American Educational Research Association. The results of the study, which focused on community college programs in Washington State, are in line with recent research in other states (Kentucky, North Carolina, and Virginia) that found only small economic returns from short-term programs. ...

2014-11-06

WASHINGTON, DC (November 6, 2014)--In honor of Veterans Day, the peer-reviewed journal Women's Health Issues (WHI) today released a new Special Collection on women veterans' health, with a focus on mental health. The special collection also highlights recent studies addressing healthcare services, reproductive health and cardiovascular health of women veterans.

"In recent years, we have seen the Veterans Administration working to improve care and health outcomes of women veterans and service members," said Chloe Bird, editor-in-chief of Women's Health Issues. "The studies ...

2014-11-06

Paramedics respond to a 911 call to find an elderly patient who's having difficulty breathing. Anxious and disoriented, the patient has trouble remembering all the medications he's taking, and with his shortness of breath, speaking is difficult. Is he suffering from acute emphysema or heart failure? The symptoms look the same, but initiating the wrong treatment regimen will increase the patient's risk of severe complications.

Researchers from MIT's Research Laboratory of Electronics, working with physicians from Harvard Medical School and the Einstein Medical Center in ...

2014-11-06

CORVALLIS, Ore. – Power outages have never been more costly. Electricity is critical to communication, transportation, commerce and national security systems, and wide-spread or prolonged outages have the potential to threaten public safety and cause millions, even billions, of dollars in damages.

"It doesn't seem that dire until a storm hits, or somebody makes a mistake, and then you are risking a blackout," said Inara Scott, an assistant professor in the College of Business at Oregon State University.

"You have to consider the magnitude of the potential harm ...

2014-11-06

High-speed reading of the genetic code should get a boost with the creation of the world's first graphene nanopores - pores measuring approximately 2 nanometers in diameter - that feature a "built-in" optical antenna. Researchers with Berkeley Lab and the University of California (UC) Berkeley have invented a simple, one-step process for producing these nanopores in a graphene membrane using the photothermal properties of gold nanorods.

"With our integrated graphene nanopore with plasmonic optical antenna, we can obtain direct optical DNA sequence detection," says Luke ...

2014-11-06

ATLANTA, GA (November 6, 2014) – Whether allergy sufferers have symptoms that are mild or severe, they really only want one thing: relief. So it's particularly distressing that the very medication they hope will ease symptoms can cause different, sometimes more severe, allergic responses.

According to a presentation at the American College of Allergy, Asthma and Immunology (ACAAI) Annual Scientific Meeting, an allergic response to a medication for allergies can often go undiagnosed. The presentation sheds light on adverse responses to topical skin preparations; ...

2014-11-06

Berlin, Germany (November, 2014) – A specimen of the ancient horse Eurohippus messelensis has been discovered in Germany that preserves a fetus as well as parts of the uterus and associated tissues. It demonstrates that reproduction in early horses was very similar to that of modern horses, despite great differences in size and structure. Eurohippus messelensis had four toes on each forefoot and three toes on each the hind foot, and it was about the size of a modern fox terrier. The new find was unveiled at the 2014 Annual Meeting of the Society of Vertebrate Paleontology ...

2014-11-06

VIDEO:

Scientists at the SUNY College of Environmental Science and Forestry (ESF) are growing the first American chestnut trees that can withstand the blight that virtually eliminated the once-dominant tree from...

Click here for more information.

SYRACUSE, N.Y. — Scientists at the SUNY College of Environmental Science and Forestry (ESF) are growing the first American chestnut trees that can withstand the blight that virtually eliminated the once-dominant tree from the eastern ...

LAST 30 PRESS RELEASES:

[Press-News.org] Manipulating complex molecules by hand

New method in scanning probe microscopy: Jülich researchers create a word using 47 molecules