(Press-News.org) Not long ago, it would have taken several years to run a high-resolution simulation on a global climate model. But using some of the most powerful supercomputers now available, Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory (Berkeley Lab) climate scientist Michael Wehner was able to complete a run in just three months.

What he found was that not only were the simulations much closer to actual observations, but the high-resolution models were far better at reproducing intense storms, such as hurricanes and cyclones. The study, "The effect of horizontal resolution on simulation quality in the Community Atmospheric Model, CAM5.1," has been published online in the Journal of Advances in Modeling Earth Systems.

"I've been calling this a golden age for high-resolution climate modeling because these supercomputers are enabling us to do gee-whiz science in a way we haven't been able to do before," said Wehner, who was also a lead author for the recent Fifth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC). "These kinds of calculations have gone from basically intractable to heroic to now doable."

Using version 5.1 of the Community Atmospheric Model, developed by the Department of Energy (DOE) and the National Science Foundation (NSF) for use by the scientific community, Wehner and his co-authors conducted an analysis for the period 1979 to 2005 at three spatial resolutions: 25 km, 100 km, and 200 km. They then compared those results to each other and to observations.

One simulation generated 100 terabytes of data, or 100,000 gigabytes. The computing was performed at Berkeley Lab's National Energy Research Scientific Computing Center (NERSC), a DOE Office of Science User Facility. "I've literally waited my entire career to be able to do these simulations," Wehner said.

The higher resolution was particularly helpful in mountainous areas since the models take an average of the altitude in the grid (25 square km for high resolution, 200 square km for low resolution). With more accurate representation of mountainous terrain, the higher resolution model is better able to simulate snow and rain in those regions.

"High resolution gives us the ability to look at intense weather, like hurricanes," said Kevin Reed, a researcher at the National Center for Atmospheric Research (NCAR) and a co-author on the paper. "It also gives us the ability to look at things locally at a lot higher fidelity. Simulations are much more realistic at any given place, especially if that place has a lot of topography."

The high-resolution model produced stronger storms and more of them, which was closer to the actual observations for most seasons. "In the low-resolution models, hurricanes were far too infrequent," Wehner said.

The IPCC chapter on long-term climate change projections that Wehner was a lead author on concluded that a warming world will cause some areas to be drier and others to see more rainfall, snow, and storms. Extremely heavy precipitation was projected to become even more extreme in a warmer world. "I have no doubt that is true," Wehner said. "However, knowing it will increase is one thing, but having a confident statement about how much and where as a function of location requires the models do a better job of replicating observations than they have."

Wehner says the high-resolution models will help scientists to better understand how climate change will affect extreme storms. His next project is to run the model for a future-case scenario. Further down the line, Wehner says scientists will be running climate models with 1 km resolution. To do that, they will have to have a better understanding of how clouds behave.

"A cloud system-resolved model can reduce one of the greatest uncertainties in climate models, by improving the way we treat clouds," Wehner said. "That will be a paradigm shift in climate modeling. We're at a shift now, but that is the next one coming."

INFORMATION:

The paper's other co-authors include Fuyu Li, Prabhat, and William Collins of Berkeley Lab; and Julio Bacmeister, Cheng-Ta Chen, Christopher Paciorek, Peter Gleckler, Kenneth Sperber, Andrew Gettelman, and Christiane Jablonowski from other institutions. The research was supported by the Biological and Environmental Division of the Department of Energy's Office of Science.

Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory addresses the world's most urgent scientific challenges by advancing sustainable energy, protecting human health, creating new materials, and revealing the origin and fate of the universe. Founded in 1931, Berkeley Lab's scientific expertise has been recognized with 13 Nobel prizes. The University of California manages Berkeley Lab for the U.S. Department of Energy's Office of Science. For more, visit http://www.lbl.gov.

DOE's Office of Science is the single largest supporter of basic research in the physical sciences in the United States, and is working to address some of the most pressing challenges of our time. For more information, please visit science.energy.gov.

The human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) can insert itself at different locations in the DNA of its human host - and this specific integration site determines how quickly the disease progresses, report researchers at KU Leuven's Laboratory for Molecular Virology and Gene Therapy. The study was published online today in the journal Cell Host & Microbe.

When HIV enters the bloodstream, virus particles bind to and invade human immune cells. HIV then reprogrammes the hijacked cell to make new HIV particles.

The HIV protein integrase plays a key role in this process: it ...

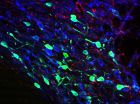

Details of the role of glutamate, the brain's excitatory chemical, in a drug reward pathway have been identified for the first time.

This discovery in rodents - published today in Nature Communications - shows that stimulation of glutamate neurons in a specific brain region (the dorsal raphe nucleus) leads to activation of dopamine-containing neurons in the brain's reward circuit (dopamine reward system).

Dopamine is a neurotransmitter present in regions of the brain that regulate movement, emotion, motivation, and feelings of pleasure. Glutamate is a neurotransmitter ...

HANOVER, N.H. - China's anti-logging, conservation and ecotourism policies are accelerating the loss of old-growth forests in one of the world's most ecologically fragile places, according to studies led by a Dartmouth College scientist.

The findings shed new light on the complex interactions between China's development and conservation policies and their impact on the most diverse temperate forests in the world, in "Shangri-La" in northwest Yunnan Province. Shangri-La, until recently an isolated Himalayan hinterland, is now the epicenter of China's struggle to wed sustainable ...

The "surfactant" chemicals found in samples of fracking fluid collected in five states were no more toxic than substances commonly found in homes, according to a first-of-its-kind analysis by researchers at the University of Colorado Boulder.

Fracking fluid is largely comprised of water and sand, but oil and gas companies also add a variety of other chemicals, including anti-bacterial agents, corrosion inhibitors and surfactants. Surfactants reduce the surface tension between water and oil, allowing for more oil to be extracted from porous rock underground.

In a new ...

Action movies may drive box office revenues, but dramas and deeper, more serious movies earn audience acclaim and appreciation, according to a team of researchers.

"Most people think that entertainment is just a silly diversion, but our research shows that entertainment is profoundly meaningful and moving for many people," said Mary Beth Oliver, Distinguished Professor in Media Studies and co-director of Media Effects Research Laboratory, Penn State. "It's not just types of entertainment that we usually think of as meaningful, such as poetry and dance, either, but also ...

Shark populations in the Mediterranean are highly divided, an international team of scientists, led by Dr Andrew Griffiths of the University of Bristol, has shown. Many previous studies on sharks suggest they move over large distances. But catsharks in the Mediterranean Sea appear to move and migrate much less, as revealed by this study. This could have important implications for conserving and managing sharks more widely, suggesting they may be more vulnerable to over-fishing than previously thought.

The study, published in the new journal Royal Society Open Science, ...

Providing health information on the internet may not be the "cure all" that it is hoped to be. It could sideline especially those Americans older than 65 years old who are not well versed in understanding health matters, and who do not use the web regularly. So says Helen Levy of the University of Michigan in the US, who led the first-ever study to show that elderly people's knowledge of health matters, so-called health literacy, also predicts how and if they use the internet. The findings¹ appear in the Journal of General Internal Medicine², published by Springer.

Substantial ...

Learning a new language changes your brain network both structurally and functionally, according to Penn State researchers.

"Learning and practicing something, for instance a second language, strengthens the brain," said Ping Li, professor of psychology, linguistics and information sciences and technology. "Like physical exercise, the more you use specific areas of your brain, the more it grows and gets stronger."

Li and colleagues studied 39 native English speakers' brains over a six-week period as half of the participants learned Chinese vocabulary. Of the subjects ...

The tree has been an effective model of evolution for 150 years, but a Rice University computer scientist believes it's far too simple to illustrate the breadth of current knowledge.

Rice researcher Luay Nakhleh and his group have developed PhyloNet, an open-source software package that accounts for horizontal as well as vertical inheritance of genetic material among genomes. His "maximum likelihood" method, detailed this month in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, allows PhyloNet to infer network models that better describe the evolution of certain ...

Most community-based mental health providers are not well prepared to take care of the special needs of military veterans and their families, according to a new study by the RAND Corporation that was commissioned by United Health Foundation in collaboration with the Military Officers Association of America.

The exploratory report, based on a survey of mental health providers nationally, found few community-based providers met criteria for military cultural competency or used evidence-based approaches to treat problems commonly seen among veterans.

"Our findings suggest ...