(Press-News.org) In the fight against HIV, microbicides--chemical compounds that can be applied topically to the female genital tract to protect against sexually transmitted infections--have been touted as an effective alternative to condoms. However, while these compounds are successful at preventing transmission of the virus in a petri dish, clinical trials using microbicides have largely failed. A new study from the Gladstone Institutes and the University of Ulm now reveals that this discrepancy may be due to the primary mode of transportation of the virus during sexual transmission, semen.

"We think this may be one of the factors explaining why so many drugs that efficiently blocked HIV infection in laboratory experiments did not work in a real world setting," explains co-first author Nadia Roan, PhD, a visiting scientist at Gladstone and an assistant professor-in-residence in the Department of Urology at the University of California, San Francisco. "We've shown previously that semen enhances HIV infection, but this is the first time we've shown that this activity markedly reduces the antiviral efficacy of microbicides."

In the study, published today in Science Translational Medicine, researchers tested the effectiveness of several different types of microbicides targeting the HIV virus on cells that had been exposed to HIV alone compared with cells that were treated with both HIV and semen. Across the board, they saw that not only did the cells with semen have rates of HIV infection approximately ten-fold higher than normal, these microbicides were up to twenty times less effective at blocking the virus in these cells than in those not exposed to semen.

Semen markedly enhances the infectiousness of HIV through the presence of protein aggregates called amyloid fibrils. HIV binds to these fibrils, causing the virus to cluster together and increasing its ability to attach to and infect cells in the host--in this case the sexual partner of the infected individual. This effect is then sufficient to increase the infectiousness of the HIV virus, thereby diminishing the antiviral properties of the microbicides.

Senior author Jan Munch, PhD, from the University of Ulm says, "Our findings suggest that targeting amyloids in semen is an alternative strategy to improve drug efficacy. The next step is to create a compound or cocktail of drugs that targets both the HIV virus and these amyloid fragments and to test its effectiveness. Also, given that semen is the main means of transmission of HIV, future testing of microbicides in the lab should be performed in the presence of semen to better predict antiretroviral efficacy in real life."

To test that it was the HIV-enhancing ability of semen that was having this effect on the microbicides and not some other substance, the researchers repeated the experiments using semen from men whose semen does not enhance HIV infection due to a disorder called ejaculatory duct obstruction. In the presence of these samples, there was no decrease in effectiveness of the anti-viral microbicides, confirming the importance of the HIV-promoting effects of semen in counteracting the effectiveness of these drugs.

Most microbicides work by targeting the virus itself, attempting to break it down or blocking its ability to infect a cell. However, the heightened infectiousness of HIV in the presence of semen appears to over-power any anti-viral effects the microbicides possess. The one exception to this finding is a different type of microbicide that acts on the host cells' receptors, stopping the virus from latching on from within. In the current study, this microbicide, called Maraviroc, was equally effective in preventing infection both with and without the presence of semen.

"There are important potential clinical implications for this study," says Warner Greene, MD, PhD, director of the Gladstone Institute of Virology and Immunology and a senior author on the paper. "Microbicides were originally developed as a way to empower and protect women in sub-Saharan Africa who often don't have a way to negotiate safe sex or condom use. However, the first generation of microbicides were largely ineffective or worse, some even leading to increased transmission of the virus. This study sheds light on why these microbicides did not work, and it provides us with a way to fix this problem by creating a new compound drug combining antivirals and amyloid inhibitors."

INFORMATION:

This research was conducted in collaboration with scientists from the University of Ulm, in Germany, and the Kindsley F. Kimball Research Institute, New York Blood Center. It was funded by the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (German Research Foundation), the Ministerium für Wissenschaft, Forschung und Kunst, Baden-Württemberg, the National Institutes of Health, National Institutes of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, and the European Research Council.

About the Gladstone Institutes

To ensure our work does the greatest good, the Gladstone Institutes focus on conditions with profound medical, economic, and social impact - unsolved diseases of the brain, the heart, and the immune system. Affiliated with the University of California, San Francisco, Gladstone is an independent, nonprofit life science research organization that uses visionary science and technology to overcome disease.

About UCSF

UCSF is a leading university dedicated to promoting health worldwide through advanced biomedical research, graduate-level education in the life sciences and health professions, and excellence in patient care. It includes top-ranked graduate schools of dentistry, medicine, nursing and pharmacy, a graduate division with nationally renowned programs in basic, biomedical, translational and population sciences, as well as a preeminent biomedical research enterprise and two top-ranked hospitals, UCSF Medical Center and UCSF Benioff Children's Hospital San Francisco.

VIDEO:

The video illustrates the complete experiment. First the participant shown wearing the Oculus head-mounted display and the OptiTrack motion capture suit gives comfort to the crying virtual child. We see...

Click here for more information.

Self-compassion can be learned using avatars in an immersive virtual reality, finds new research led by UCL. This innovative approach reduced self-criticism and increased self-compassion and feelings of contentment in naturally self-critical ...

It is claimed one in five students have taken the 'smart' drug Modafinil to boost their ability to study and improve their chances of exam success. But new research into the effects of Modafinil has shown that healthy students could find their performance impaired by the drug.

The study carried out by Dr Ahmed Dahir Mohamed, in the School of Psychology at The University of Nottingham Malaysia Campus, and published today, Wednesday 12 November 2014, in the open access journal PLOS ONE, showed the drug had negative effects in healthy people.

Dr Mohamed said: "We looked ...

CORAL GABLES, Fla. (Nov. 12, 2014) -- Crowdsourcing utilizes the input of a crowd of online users to collaboratively solve problems. To advance this emerging technology, researchers at the University of Miami are developing a computing model that uses crowdsourcing to combine and optimize human efforts and machine computing elements.

The new model can be used to efficiently perform the complex tasks of face recognition--a method used in law enforcement. It's a new approach to using social networks as a formal part of the criminal investigation process, explained computer ...

Making friends is often extremely difficult for people with social anxiety disorder and to make matters worse, people with this disorder tend to assume that the friendships they do have are not of the highest quality.

The problem with this perception, suggests new research from Washington University in St. Louis, is that it's not necessarily true from the point of view of their friends.

"People who are impaired by high social anxiety typically think they are coming across much worse than they really are," said study co-author Thomas Rodebaugh, PhD, associate professor ...

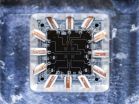

While the Martinis Lab at UC Santa Barbara has been focusing on quantum computation, former postdoctoral fellow Pedram Roushan and several colleagues have been exploring qubits (quantum bits) for quantum simulation on a smaller scale. Their research appears in the current edition of the journal Nature.

"While we're waiting on quantum computers, there are specific problems from various fields ranging from chemistry to condensed matter that we can address systematically with superconducting qubits," said Roushan, who is now a quantum electronics engineer at Google. "These ...

It's not uncommon to see cameras mounted on store ceilings, propped up in public places or placed inside subways, buses and even on the dashboards of cars.

Cameras record our world down to the second. This can be a powerful surveillance tool on the roads and in buildings, but it's surprisingly hard to sift through vast amounts of visual data to find pertinent information - namely, making a split-second identification and understanding a person's actions and behaviors as recorded sequentially by cameras in a variety of locations.

Now, University of Washington electrical ...

ITHACA, N.Y. - Peering deep into time with one of the world's newest, most sophisticated telescopes, astronomers have found a galaxy - AzTEC-3 - that gives birth annually to 500 times the number of suns as the Milky Way galaxy, according to a new Cornell University-led study published Nov. 10 in the Astrophysical Journal.

Lead author Dominik Riechers, Cornell assistant professor of astronomy, and an international team of researchers gazed back - with the Atacama Large Millimeter/submillimeter Array (ALMA) in Chile - over 12.5 billion years to find bustling galaxies creating ...

New York, NY - The female mosquitoes that spread dengue and yellow fever didn't always rely on human blood to nourish their eggs. Their ancestors fed on furrier animals in the forest. But then, thousands of years ago, some of these bloodsuckers made a smart switch: They began biting humans and hitchhiked all over the globe, spreading disease in their wake.

"It was a really good evolutionary move," says Leslie B. Vosshall, the Robin Chemers Neustein Professor and head of the Laboratory of Neurogenetics and Behavior at The Rockefeller University, and a Howard Hughes Medical ...

As cities and incomes increase around the world, so does consumption of refined sugars, refined fats, oils and resource- and land-intense agricultural products such as beef. A new study led by University of Minnesota ecologist David Tilman shows how a shift away from this trajectory and toward healthier traditional Mediterranean, pescatarian or vegetarian diets could not only boost human lifespan and quality of life, but also slash greenhouse gas emissions and save habitat for endangered species.

The study, published in the November 12 online edition of Nature by Tilman ...

Menlo Park, Calif. -- A study at the Department of Energy's SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory suggests for the first time how scientists might deliberately engineer superconductors that work at higher temperatures.

In their report, a team led by SLAC and Stanford University researchers explains why a thin layer of iron selenide superconducts -- carries electricity with 100 percent efficiency -- at much higher temperatures when placed atop another material, which is called STO for its main ingredients strontium, titanium and oxygen.

These findings, described today ...