"It was a really good evolutionary move," says Leslie B. Vosshall, the Robin Chemers Neustein Professor and head of the Laboratory of Neurogenetics and Behavior at The Rockefeller University, and a Howard Hughes Medical Institute investigator. "We provide the ideal lifestyle for mosquitoes. We always have water around for them to breed in, we are hairless, and we live in large groups."

To understand the evolutionary basis of this attraction, Vosshall and her colleagues examined the genes that drive some mosquitoes to prefer humans. Their findings, published in the November 13 issue of Nature, suggest that human-loving mosquitos are attracted to our scent. "They've acquired a love for human body odor, and that's a key step in specializing on us," she says.

The quest to understand what makes some mosquitoes prefer humans began in Rabai, Kenya. In the 1960s and 1970s, scientists visiting the region observed two distinct populations living just hundreds of meters apart. Black mosquitoes, a subspecies called Aedes aegypti formosus, tended to lay its eggs outdoors and preferred to bite forest animals. Their light-brown cousins, Aedes aegypti aegypti, tended to breed indoors in water jugs and mostly hunted humans. "We think we can get a glimpse of what happened thousands of years ago by looking at this little village in Kenya because the players are still there," Vosshall says.

In 2009, Carolyn McBride, who was a postdoc in Vosshall's laboratory at the time, and her co-investigators travelled to Rabai to see if these two groups still existed. The team used turkey basters to collect larvae from tree holes in the forest and sieved larvae from clay pots and metal cans inside people's homes. Back in the lab in New York they reared the insects and discovered that the observations that researchers had made years earlier seemed to hold true: The insects collected indoors tended to be light brown, and when given the option to bite humans or guinea pigs, they mostly choose humans. Those collected in the forest were black and tended to prefer the laboratory guinea pigs.

To zero in on the genes responsible for the human-loving mosquitoes' preference, the researchers crossbred the mosquitoes, creating thousands of genetically diverse grandchildren. And then they sorted those mosquitoes based on their odor preference and compared the two groups.

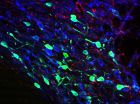

"We knew that these mosquitoes had evolved a love for the way we smell," Vosshall says. So she and her colleagues looked specifically for genes that had higher levels of expression in the human-loving insects' antennae. These structures contain proteins called odorant receptors that pick up different scents.

Vosshall and her colleagues found 14 genes strongly linked to liking humans, but one odor receptor gene - Or4 - stood out. "It's very highly expressed in human-preferring mosquitoes," Vosshall says.

The researchers guessed that Or4 must be detecting some aroma in human body odor. To figure out which one, they asked volunteers to wear pantyhose for 24 hours. And then they placed those stinky stockings in a machine designed to separate their scent into the hundreds of individual chemicals that make up body odor. The researchers came up with one match, a chemical called sulcatone that was not found in pantyhose worn by guinea pigs.

Sulcatone is an important odor that gives humans our distinctive scent, but there are likely other odors and other genes that help explain mosquitoes' attraction to humans. In fact, adding sulcatone to the guinea pig odor didn't make guinea pig scent more appealing to human-loving mosquitoes. McBride, now at Princeton University, plans to look for other factors to help explain how mosquitoes transitioned from harmless animal-biting insects into deadly vectors of human disease.

The switch from preferring animals to humans involves a variety of behavior adjustments: Mosquitoes had to become comfortable living around humans, entering their homes, breeding in clean water found in water jugs instead of the muddy water found in tree holes. "There's a whole suite of things that mosquitoes have to change about their lifestyle to live around humans," Vosshall says. "This paper provides the first genetic insight into what happened thousands of years ago when some mosquitoes made this switch."

INFORMATION:

McBride is lead author on the Nature study, and Vosshall is senior author. Their coauthors are: Felix Baier and Sarabeth A. Spitzer in Vosshall's laboratory; Aman B. Omondi and Rickard Ignell with the Swedish University of Agricultural Sciences in Alnarp; and Joel Lutomiah and Rosemary Sang with the Kenya Medical Research Institute in Nairobi.

About The Rockefeller University

Founded by John D. Rockefeller in 1901, The Rockefeller University was this nation's first biomedical research institution. Hallmarks of the university include a research environment that provides scientists with the support they need to do imaginative science and a truly international graduate program that is unmatched for the freedom and resources it provides students to develop their capacities for innovative research. The Rockefeller University Hospital, founded in 1910 as the first center for clinical research in the United States, remains a place where researchers combine laboratory investigations with bedside observations to provide a scientific basis for disease detection, prevention, and treatment. Since the institution's founding, Rockefeller University has been the site of many important scientific breakthroughs. Rockefeller scientists, for example, established that DNA is the chemical basis of heredity, identified the weight-regulating hormone leptin, discovered blood groups, showed that viruses can cause cancer, founded the modern field of cell biology, worked out the structure of antibodies, devised the AIDS "cocktail" drug therapy, and developed methadone maintenance for people addicted to heroin. Throughout Rockefeller's history, 24 scientists associated with the university have received the Nobel Prize in physiology/medicine and chemistry, and 21 scientists associated with the university have been honored with the Albert Lasker Medical Research Award. Eighteen Rockefeller University scientists have received the Canada Gairdner Award, and 20 have garnered the National Medal of Science. Currently, the university's award-winning faculty includes five Nobel laureates, seven Lasker Award winners, 10 Canada Gairdner Award honorees, and three recipients of the National Medal of Science. Thirty-three of the faculty members are elected members of the National Academy of Sciences, and 17 are members of the Institute of Medicine. For more information, go to http://www.rockefeller.edu.