(Press-News.org) A research team led by Jackson Laboratory Professors Frank McKeon, Ph.D., and Wa Xian, Ph.D., reports on the role of certain lung stem cells in regenerating lungs damaged by disease.

The work, published Nov. 12 in the journal Nature, sheds light on the inner workings of the still-emerging concept of lung regeneration and points to potential therapeutic strategies that harness these lung stem cells.

"The idea that the lung can regenerate has been slow to take hold in the biomedical research community," McKeon says, "in part because of the steady decline that is seen in patients with severe lung diseases like chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (known as COPD) and pulmonary fibrosis."

Nevertheless, he notes, there are examples in humans that point to the existence of a robust system for lung regeneration. "Some survivors of acute respiratory distress syndrome, or ARDS, for example, are able to recover near-normal lung function following significant destruction of lung tissue."

Mice appear to share this capacity. Mice infected with the H1N1 influenza virus show progressive inflammation in the lung followed by outright loss of important lung cell types. Yet over several weeks, the lungs recover, revealing no signs of the previous lung injury.

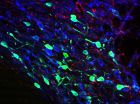

Using this mouse model system, McKeon and his colleagues had previously identified a type of adult lung stem cell known as p63+/Krt5+ in the distal airways. When grown in culture, these lung stem cells formed alveolar-like structures, similar to the alveoli found within the lung. (Alveoli are the tiny, specialized air sacs that form at the ends of the smallest airways, where gas exchange occurs in the lung.) Following infection with H1N1, these same cells migrated to sites of inflammation in the lung and assembled into pod-like structures that resemble alveoli, both visually and molecularly.

In the new paper, the research team reports that the p63+/Krt5+ lung stem cells proliferate upon damage to the lung caused by H1N1 infection. Following such damage, the cells go on to contribute to developing alveoli near sites of lung inflammation.

To test whether these cells are required for lung regeneration, the researchers developed a novel system that leverages genetic tools to selectively remove these cells from the mouse lung. Mice lacking the p63+/Krt5+ lung stem cells cannot recover normally from H1N1 infection, and exhibit scarring of the lung and impaired oxygen exchange--demonstrating their key role in regenerating lung tissue.

The research team also showed that when individual lung stem cells are isolated and subsequently transplanted into a damaged lung, they readily contribute to the formation of new alveoli, underscoring their capacity for regeneration.

In the U.S. about 200,000 people have ARDS, a disease with a death rate of 40 percent, and there are 12 million patients with COPD. "These patients have few therapeutic options today," Xian says. "We hope that our research could lead to new ways to help them."

INFORMATION:

The JAX researchers collaborated with scientists at Genome Institute of Singapore, Advanced Cell Technologies in Marlborough, Mass., Brigham and Women's Hospital of Harvard Medical School in Boston, National University Health System in Singapore and the University of Connecticut Health Center in Farmington, Conn. The work was supported by grants from the Joint Council Office of the Agency for Science Technology Research (ASTAR) in Singapore, the U.S. Defense Advanced Research Project Agency, the Johnson & Johnson ASTAR Joint Program and Connecticut Innovations.

The Jackson Laboratory is an independent, nonprofit biomedical research institution and National Cancer Institute-designated Cancer Center based in Bar Harbor, Maine, with a facility in Sacramento, Calif., and a new genomic medicine institute in Farmington, Conn. It employs 1,600 staff, and its mission is to discover precise genomic solutions for disease and empower the global biomedical community in the shared quest to improve human health.

Zuo et al.: "p63+/Krt5+ distal airway stem cells are essential for lung regeneration." Nature, 11/12/14, DOI: 10.1038/nature13903.

The brain's ability to effectively deal with stress or to lack that ability and be more susceptible to depression, depends on a single protein type in each person's brain, according to a study conducted at the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai and published November 12 in the journal Nature.

The Mount Sinai study findings challenge the current thinking about depression and the drugs currently used to treat the disorder.

"Our findings are distinct from serotonin and other neurotransmitters previously implicated in depression or resilience against it," says the ...

Not long ago, it would have taken several years to run a high-resolution simulation on a global climate model. But using some of the most powerful supercomputers now available, Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory (Berkeley Lab) climate scientist Michael Wehner was able to complete a run in just three months.

What he found was that not only were the simulations much closer to actual observations, but the high-resolution models were far better at reproducing intense storms, such as hurricanes and cyclones. The study, "The effect of horizontal resolution on simulation ...

The human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) can insert itself at different locations in the DNA of its human host - and this specific integration site determines how quickly the disease progresses, report researchers at KU Leuven's Laboratory for Molecular Virology and Gene Therapy. The study was published online today in the journal Cell Host & Microbe.

When HIV enters the bloodstream, virus particles bind to and invade human immune cells. HIV then reprogrammes the hijacked cell to make new HIV particles.

The HIV protein integrase plays a key role in this process: it ...

Details of the role of glutamate, the brain's excitatory chemical, in a drug reward pathway have been identified for the first time.

This discovery in rodents - published today in Nature Communications - shows that stimulation of glutamate neurons in a specific brain region (the dorsal raphe nucleus) leads to activation of dopamine-containing neurons in the brain's reward circuit (dopamine reward system).

Dopamine is a neurotransmitter present in regions of the brain that regulate movement, emotion, motivation, and feelings of pleasure. Glutamate is a neurotransmitter ...

HANOVER, N.H. - China's anti-logging, conservation and ecotourism policies are accelerating the loss of old-growth forests in one of the world's most ecologically fragile places, according to studies led by a Dartmouth College scientist.

The findings shed new light on the complex interactions between China's development and conservation policies and their impact on the most diverse temperate forests in the world, in "Shangri-La" in northwest Yunnan Province. Shangri-La, until recently an isolated Himalayan hinterland, is now the epicenter of China's struggle to wed sustainable ...

The "surfactant" chemicals found in samples of fracking fluid collected in five states were no more toxic than substances commonly found in homes, according to a first-of-its-kind analysis by researchers at the University of Colorado Boulder.

Fracking fluid is largely comprised of water and sand, but oil and gas companies also add a variety of other chemicals, including anti-bacterial agents, corrosion inhibitors and surfactants. Surfactants reduce the surface tension between water and oil, allowing for more oil to be extracted from porous rock underground.

In a new ...

Action movies may drive box office revenues, but dramas and deeper, more serious movies earn audience acclaim and appreciation, according to a team of researchers.

"Most people think that entertainment is just a silly diversion, but our research shows that entertainment is profoundly meaningful and moving for many people," said Mary Beth Oliver, Distinguished Professor in Media Studies and co-director of Media Effects Research Laboratory, Penn State. "It's not just types of entertainment that we usually think of as meaningful, such as poetry and dance, either, but also ...

Shark populations in the Mediterranean are highly divided, an international team of scientists, led by Dr Andrew Griffiths of the University of Bristol, has shown. Many previous studies on sharks suggest they move over large distances. But catsharks in the Mediterranean Sea appear to move and migrate much less, as revealed by this study. This could have important implications for conserving and managing sharks more widely, suggesting they may be more vulnerable to over-fishing than previously thought.

The study, published in the new journal Royal Society Open Science, ...

Providing health information on the internet may not be the "cure all" that it is hoped to be. It could sideline especially those Americans older than 65 years old who are not well versed in understanding health matters, and who do not use the web regularly. So says Helen Levy of the University of Michigan in the US, who led the first-ever study to show that elderly people's knowledge of health matters, so-called health literacy, also predicts how and if they use the internet. The findings¹ appear in the Journal of General Internal Medicine², published by Springer.

Substantial ...

Learning a new language changes your brain network both structurally and functionally, according to Penn State researchers.

"Learning and practicing something, for instance a second language, strengthens the brain," said Ping Li, professor of psychology, linguistics and information sciences and technology. "Like physical exercise, the more you use specific areas of your brain, the more it grows and gets stronger."

Li and colleagues studied 39 native English speakers' brains over a six-week period as half of the participants learned Chinese vocabulary. Of the subjects ...