(Press-News.org) The brain's ability to effectively deal with stress or to lack that ability and be more susceptible to depression, depends on a single protein type in each person's brain, according to a study conducted at the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai and published November 12 in the journal Nature.

The Mount Sinai study findings challenge the current thinking about depression and the drugs currently used to treat the disorder.

"Our findings are distinct from serotonin and other neurotransmitters previously implicated in depression or resilience against it," says the study's lead investigator, Eric J. Nestler, MD, PhD, Nash Family Professor, Chair of the Department of Neuroscience and Director of the Friedman Brain Institute at the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai. "These data provide a new pathway to find novel and potentially more effective antidepressants."

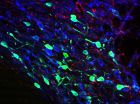

The protein involved in this new model of depression is beta-catenin (B-catenin), which is expressed throughout the brain and is known to have many biological roles. Using mouse models exposed to chronic social stress, Mount Sinai investigators discovered that it is the activity of the protein in the D2 neurons, a specific set of nerve cells (neurons) in the nucleus accumbens (NAc), the brain's reward and motivation center, which drives resiliency.

Specifically, the research team found that animals whose brains activated B-catenin were protected against stress, while those with inactive B-catenin developed signs of depression in their behavior. The study also showed suppression of this protein in brain tissue of depressed patients examined post mortem.

"Our human data are notable in that we show decreased activation of B-catenin in depressed humans, regardless of whether these individuals were on or off antidepressants at the time of death," says the study's co-lead investigator, Caroline Dias, an MD-PhD student at the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai. "This implies that the antidepressants were not adequately targeting this brain system."

In the study, researchers blocked B-catenin in the D2 brain cells in mice that had previously shown resilience to depression and found the animals became susceptible to stress. Conversely, activating B-catenin in stress mice bolstered their resilience to stress.

Nearly all nerve cells in the NAc brain region are called medium spiny neurons. These cells are divided into two types based on how they detect the neurotransmitter dopamine, which is important in regulating reward and motivation. One type of neuron detects dopamine with D1 receptors and the other with D2 receptors. The Mount Sinai data specifically implicate the D2 neurons in mediating deficits in reward and motivation that contribute to depression or enhancements that mediate resilience.

Examining the genes regulated by B-catenin, the team then traced the pathway that was engaged when B-catenin was activated in the D2 neurons and discovered a novel connection between the protein and Dicer1, an enzyme important in making microRNAs, small molecules which control gene expression.

"While we have identified some of the genes that are targeted, future studies will be key to see how these genes affect depression. Presumably, they are important in mediating the pro-resilient effects of the B-catenin-Dicer cascade," says Dr. Dias.

While the molecular underpinnings of depression have remained elusive despite decades of research, the new Mount Sinai study breaks new ground in understanding depression in three important ways. It is the first report that B-catenin is deficient in nucleus accumbens in human depression and mouse depression models; it is the first study to show that higher activity of B-catenin drives resilience and the first report demonstrating a strong connection between B-catenin and control of microRNA synthesis.

The findings also suggest that future therapy for depression could be aimed at bolstering resilience against stress.

"While most prior efforts in antidepressant drug discovery have focused on ways to undo the bad effects of stress, our findings provide a pathway to generate novel antidepressants that instead activate mechanisms of natural resilience," says Dr. Nestler.

INFORMATION:

This work was supported by grants from the National Institute of Mental Health and Hope for Depression Research Foundation.

Researchers from the University of Texas Southwestern, the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Michigan State University, the UCLA College of Life Sciences, the University of Arizona College of Medicine and the Institut National de la Sante et de la Recherhe Medicale (INSERM) in Paris contributed to the study.

About the Mount Sinai Health System

The Mount Sinai Health System is an integrated health system committed to providing distinguished care, conducting transformative research, and advancing biomedical education. Structured around seven member hospital campuses and a single medical school, the Health System has an extensive ambulatory network and a range of inpatient and outpatient services--from community‐based facilities to tertiary and quaternary care.

The System includes approximately 6,600 primary and specialty care physicians, 12‐minority‐owned free‐standing ambulatory surgery centers, over 45 ambulatory practices throughout the five boroughs of New York City, Westchester, and Long Island, as well as 31 affiliated community health centers. Physicians are affiliated with the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, which is ranked among the top 20 medical schools both in National Institutes of Health funding and by U.S. News & World Report.

For more information, visit http://www.mountsinai.org, or find Mount Sinai on Facebook, Twitter and YouTube.

Not long ago, it would have taken several years to run a high-resolution simulation on a global climate model. But using some of the most powerful supercomputers now available, Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory (Berkeley Lab) climate scientist Michael Wehner was able to complete a run in just three months.

What he found was that not only were the simulations much closer to actual observations, but the high-resolution models were far better at reproducing intense storms, such as hurricanes and cyclones. The study, "The effect of horizontal resolution on simulation ...

The human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) can insert itself at different locations in the DNA of its human host - and this specific integration site determines how quickly the disease progresses, report researchers at KU Leuven's Laboratory for Molecular Virology and Gene Therapy. The study was published online today in the journal Cell Host & Microbe.

When HIV enters the bloodstream, virus particles bind to and invade human immune cells. HIV then reprogrammes the hijacked cell to make new HIV particles.

The HIV protein integrase plays a key role in this process: it ...

Details of the role of glutamate, the brain's excitatory chemical, in a drug reward pathway have been identified for the first time.

This discovery in rodents - published today in Nature Communications - shows that stimulation of glutamate neurons in a specific brain region (the dorsal raphe nucleus) leads to activation of dopamine-containing neurons in the brain's reward circuit (dopamine reward system).

Dopamine is a neurotransmitter present in regions of the brain that regulate movement, emotion, motivation, and feelings of pleasure. Glutamate is a neurotransmitter ...

HANOVER, N.H. - China's anti-logging, conservation and ecotourism policies are accelerating the loss of old-growth forests in one of the world's most ecologically fragile places, according to studies led by a Dartmouth College scientist.

The findings shed new light on the complex interactions between China's development and conservation policies and their impact on the most diverse temperate forests in the world, in "Shangri-La" in northwest Yunnan Province. Shangri-La, until recently an isolated Himalayan hinterland, is now the epicenter of China's struggle to wed sustainable ...

The "surfactant" chemicals found in samples of fracking fluid collected in five states were no more toxic than substances commonly found in homes, according to a first-of-its-kind analysis by researchers at the University of Colorado Boulder.

Fracking fluid is largely comprised of water and sand, but oil and gas companies also add a variety of other chemicals, including anti-bacterial agents, corrosion inhibitors and surfactants. Surfactants reduce the surface tension between water and oil, allowing for more oil to be extracted from porous rock underground.

In a new ...

Action movies may drive box office revenues, but dramas and deeper, more serious movies earn audience acclaim and appreciation, according to a team of researchers.

"Most people think that entertainment is just a silly diversion, but our research shows that entertainment is profoundly meaningful and moving for many people," said Mary Beth Oliver, Distinguished Professor in Media Studies and co-director of Media Effects Research Laboratory, Penn State. "It's not just types of entertainment that we usually think of as meaningful, such as poetry and dance, either, but also ...

Shark populations in the Mediterranean are highly divided, an international team of scientists, led by Dr Andrew Griffiths of the University of Bristol, has shown. Many previous studies on sharks suggest they move over large distances. But catsharks in the Mediterranean Sea appear to move and migrate much less, as revealed by this study. This could have important implications for conserving and managing sharks more widely, suggesting they may be more vulnerable to over-fishing than previously thought.

The study, published in the new journal Royal Society Open Science, ...

Providing health information on the internet may not be the "cure all" that it is hoped to be. It could sideline especially those Americans older than 65 years old who are not well versed in understanding health matters, and who do not use the web regularly. So says Helen Levy of the University of Michigan in the US, who led the first-ever study to show that elderly people's knowledge of health matters, so-called health literacy, also predicts how and if they use the internet. The findings¹ appear in the Journal of General Internal Medicine², published by Springer.

Substantial ...

Learning a new language changes your brain network both structurally and functionally, according to Penn State researchers.

"Learning and practicing something, for instance a second language, strengthens the brain," said Ping Li, professor of psychology, linguistics and information sciences and technology. "Like physical exercise, the more you use specific areas of your brain, the more it grows and gets stronger."

Li and colleagues studied 39 native English speakers' brains over a six-week period as half of the participants learned Chinese vocabulary. Of the subjects ...

The tree has been an effective model of evolution for 150 years, but a Rice University computer scientist believes it's far too simple to illustrate the breadth of current knowledge.

Rice researcher Luay Nakhleh and his group have developed PhyloNet, an open-source software package that accounts for horizontal as well as vertical inheritance of genetic material among genomes. His "maximum likelihood" method, detailed this month in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, allows PhyloNet to infer network models that better describe the evolution of certain ...