Chlamydia knock out the body's own cancer defence

By breaking down the cancer-suppressing protein p53, Chlamydia prevent programmed cell death and thereby favor the process of cancer development

2014-11-17

(Press-News.org) This news release is available in German.

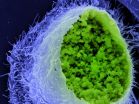

Infections due to the sexually transmitted bacterium Chlamydia trachomatis often remain unnoticed. The pathogen is not only a common cause of female infertility; it is also suspected of increasing the risk of abdominal cancer. A research team at the Max Planck Institute for Infection Biology in Berlin has now observed the breakdown of an important endogenous protective factor in the course of chlamydial infection. By activating the destruction of p53 protein, the bacterium blocks a key protective mechanism of infected cells, the initiation of programmed cell death. This protective function of p53 is also impaired in many forms of cancer. The new insights underpin the suspected relationship between chlamydial infection and the occurrence of certain types of cancers.

Hundreds of mutations occur every day in almost every cell in our body. The protein p53 is then activated in order to limit these changes in the genome: either the cell repairs the damaged DNA or, if that is not possible, it triggers the cellular suicide program. In this way, cells are normally protected against the development of cancer.

As the Berlin-based team at the Max Planck Institute for Infection Biology reported last year, chlamydial infections lead to a drastic increase in the mutation rate. Activation of the suicide program would be fatal for Chlamydia, however, as the bacteria are only able to multiply inside their host cells from which they draw their nutrients. To protect themselves, Chlamydia therefore block activation of the cellular suicide program.

With the help of colleagues from the Max Delbrück Center for Molecular Medicine and from Australia, the Max Planck team has now shown that Chlamydia ensure the survival of host cells by breaking down p53. They do so by activating a breakdown pathway that is already present in cells. The pathogens thereby gain enough time to successfully reproduce inside the cells. However, this has potentially fatal consequences for the host organism: destruction of p53, the central "guardian of the genome", increases the risk of mutant cells surviving and developing into cancer cells.

Degradation of p53 is also observed in infections with human papillomavirus, the cause of cervical cancer. Chlamydia may play a role in this disease as well. However, they penetrate much deeper into the genital tract and can cause inflammation of the fallopian tubes, where they often reside unnoticed for a long time. Ovarian cancer, one of the deadliest cancers in women, is now also believed to originate within the fallopian tubes.

"The impact of Chlamydia on p53 is an important part in the complex puzzle of cancer development. The more substantiated the relationship between infection and cancer becomes, the more important it will be to promote the development of effective vaccines and antibiotics to prevent cancer," says Thomas F. Meyer, Director at the Max Planck Institute in Berlin.

INFORMATION:

Original Paper

González E, Rother M, Kerr MC, Al-Zeer M, Abu-Lubad M, Kessler M, Brinkmann V, Loewer A & Meyer TF

Chlamydia infection depends on a functional MDM2-p53 axis

Nature Communications 2014, 13 November 2014

[Attachments] See images for this press release:

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

2014-11-17

Doctors tell us that the frenzied pace of the modern 24-hour lifestyle -- in which we struggle to juggle work commitments with the demands of family and daily life -- is damaging to our health. But while life in the slow lane may be better, will it be any longer? It will if you're a reptile.

A new study by Tel Aviv University researchers finds that reduced reproductive rates and a plant-rich diet increases the lifespan of reptiles. The research, published in the journal Global Ecology and Biogeography, was led by Prof. Shai Meiri, Dr. Inon Scharf, and doctoral student ...

2014-11-17

If you want to see into the future, you have to understand the past. An international consortium of researchers under the auspices of the University of Bonn has drilled deposits on the bed of Lake Van (Eastern Turkey) which provide unique insights into the last 600,000 years. The samples reveal that the climate has done its fair share of mischief-making in the past. Furthermore, there have been numerous earthquakes and volcanic eruptions. The results of the drilling project also provide a basis for assessing the risk of how dangerous natural hazards are for today's population. ...

2014-11-17

WASHINGTON, D.C. - Two or more serious hits to the head within days of each other can interfere with the brain's ability to use sugar - its primary energy source - to repair cells damaged by the injuries, new research suggests.

The brain's ability to use energy is critical after an injury. In animal studies, Ohio State University scientists have shown that brain cells ramp up their energy use six days after a concussion to recover from the damage. If a second injury occurs before that surge of energy use starts, the brain loses its best chance to recover.

In mice, ...

2014-11-17

Mikhail Kosiborod, M.D., of Saint Luke's Mid America Heart Institute, Kansas City, and colleagues evaluated the efficacy and safety of the drug zirconium cyclosilicate in patients with hyperkalemia (higher than normal potassium levels). The study appears in JAMA and is being released to coincide with its presentation at the American Heart Association's Scientific Sessions 2014.

Hyperkalemia is a common electrolyte disorder which can cause potentially life-threatening cardiac arrhythmias and is associated with chronic kidney disease, heart failure, and diabetes mellitus. ...

2014-11-17

BLOOMINGTON, Ind. -- An Indiana University-Dartmouth College team has identified genes and regulatory patterns that allow some organisms to alter their body form in response to environmental change.

Understanding how an organism adopts a new function to thrive in a changing environment has implications for molecular evolution and many areas of science including climate change and medicine, especially in regeneration and wound healing.

The study, which appears in the journal Molecular Biology and Evolution, provides insight into phenotypic plasticity, a phenomenon that ...

2014-11-17

November 17, 2014, PORTLAND, Ore. -- People who received automated reminders were more likely to refill their blood pressure and cholesterol medications, according to a study published today in a special issue of the American Journal of Managed Care.

The study, which included more than 21,000 Kaiser Permanente members, found that the average improvement in medication adherence was only about 2 percentage points, but the authors say that in a large population, even small changes can make a big difference.

"This small jump might not mean a lot to an individual patient, ...

2014-11-17

This news release is available in Spanish.

Although maize was originally domesticated in Mexico, the country's average yield per hectare is 38% below the world's average. In fact, Mexico imports 30% of its maize from foreign sources to keep up with internal demand.

To combat insect pests, Mexican farmers rely primarily on chemical insecticides. Approximately 3,000 tons of active ingredient are used each year just to manage the fall armyworm (Spodoptera frugiperda), in addition to even more chemicals used to control other pests such as the corn earworm (Helicoverpa ...

2014-11-17

In the aquatic environment, suction feeding is far more common than biting as a way to capture prey. A new study shows that the evolution of biting behavior in eels led to a remarkable diversification of skull shapes, indicating that the skull shapes of most fish are limited by the structural requirements for suction feeding.

"When you look at the skulls of biters, the diversity is astounding compared to suction feeders," said Rita Mehta, assistant professor of ecology and evolutionary biology at UC Santa Cruz.

With more than 800 species, including both suction feeders ...

2014-11-17

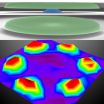

For the first time, scientists have vividly mapped the shapes and textures of high-order modes of Brownian motions--in this case, the collective macroscopic movement of molecules in microdisk resonators--researchers at Case Western Reserve University report.

To do this, they used a record-setting scanning optical interferometry technique, described in a study published today in the journal Nature Communications.

The new technology holds promise for multimodal sensing and signal processing, and to develop optical coding for computing and other information-processing ...

2014-11-17

Chronic myeloid leukemia develops when a gene mutates and causes an enzyme to become hyperactive, causing blood-forming stem cells in the bone marrow to grow rapidly into abnormal cells. The enzyme, Abl-kinase, is a member of the "kinase" family of enzymes, which serve as an "on" or "off" switch for many functions in our cells. In chronic myeloid leukemia, the hyperactive Abl-kinase is targeted with drugs that bind to a specific part of the enzyme and block it, aiming to ultimately kill the fast-growing cancer cell. However, treatments are often limited by the fact that ...

LAST 30 PRESS RELEASES:

[Press-News.org] Chlamydia knock out the body's own cancer defence

By breaking down the cancer-suppressing protein p53, Chlamydia prevent programmed cell death and thereby favor the process of cancer development