(Press-News.org) CORVALLIS, Ore. - Engineers have created a new way to use lidar technology to identify and classify landslides on a landscape scale, which may revolutionize the understanding of landslides in the U.S. and reveal them to be far more common and hazardous than often understood.

The new, non-subjective technology, created by researchers at Oregon State University and George Mason University, can analyze and classify the landslide risk in an area of 50 or more square miles in about 30 minutes - a task that previously might have taken an expert several weeks to months. It can also identify risks common to a broad area rather than just an individual site.

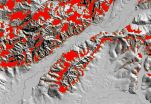

And with such speed and precision, it reveals that some landslide-prone areas of the Pacific Northwest are literally covered by landslides from one time or another in history. The system is based on new ways to use light detecting and ranging, or lidar technology, that can seemingly strip away vegetation and other obstructions to show land features in their bare form.

"With lidar we can see areas that are 50-80 percent covered by landslide deposits," said Michael Olsen, an expert in geomatics and the Eric HI and Janice Hoffman Faculty Scholar in the OSU College of Engineering. "It may turn out that there are 10-100 times more landslides in some places than we knew of before.

"We've always known landslides were a problem in the Pacific Northwest," Olsen said. "Many people are just now beginning to realize how big the problem is."

An outline of the new technology was recently published in Computers and Geosciences, a professional journal.

Oregon and Washington, especially in the Coast Range and Cascade Range, are already areas commonly known to have landslides, and as a result Oregon's Department of Geology and Mineral Industries has become a national leader in mapping of them, Olsen said. But previous approaches are slow, and the new technology, called a Contour Connection Method, could radically speed up widespread mapping, and build both professional and public awareness of the issue.

Despite the prevalence and frequency of landslides, they are not generally covered by most homeowner insurance policies; coverage can be purchased separately, but most people don't. And with increasing population growth, more and more people are moving into more remote locations, or building in scenic areas near the hills around cities where landslide risk might be high.

"A lot of people don't think in geologic terms, so if they see a hill that's been there for a long time, they assume there's no risk," said Ben Leshchinsky, a geotechnical engineer in the OSU College of Forestry. "And many times they don't want to pay extra to have an expert assess landslide risks or do something that might interfere with their land development plans."

Lidar is already a powerful tool, but the new system developed at OSU offers an automated way to improve the use of it, and could usher in a new era of landslide awareness, experts say. Information could be more routinely factored into road, bridge, land use, zoning, building and other decisions.

With this technology, a computer automatically looks for land features, such as suddenly steeper areas of soil, that might be evidence of a past landslide. It then searches the terrain for other features, such as a "toe" of soils at the base of the landslide. And in minutes it can make unbiased, science-based classifications of past landslides that consistently use the same criteria.

The technology was applied to the region surrounding the landslide of March, 2014, that killed 43 people near the small town of Oso, Washington. In about nine minutes it was able to analyze more than 2,200 acres and many prehistoric landslide features that are readily apparent in lidar images, in this region known for slope instability.

Eventually, adaptations of the technology might even allow for real-time monitoring of soil movement, the researchers said.

INFORMATION:

Editor's Note: Graphics are available to illustrate this story.

Landslide in Stillaguamish Valley, Washington: https://flic.kr/p/pQmpe3

Landslide inventory map: https://flic.kr/p/q7wexe

Oso landslide in Washington state: https://flic.kr/p/q5BgEs

TALLAHASSEE, Fla. -- A new study by a Florida State University biologist shows that bleaching events brought on by rising sea temperatures are having a detrimental long-term impact on coral.

Professor Don Levitan, chair of the Department of Biological Science, writes in the latest issue of Marine Ecology Progress Series that bleaching -- a process where high water temperatures or UV light stresses the coral to the point where it loses its symbiotic algal partner that provides the coral with color -- is also affecting the long-term fertility of the coral.

"Even corals ...

New research has found that one of the world's most prolific bacteria manages to afflict humans, animals and even plants by way of a mechanism not before seen in any infectious microorganism -- a sense of touch. This unique ability helps make the bacteria Pseudomonas aeruginosa ubiquitous, but it also might leave these antibiotic-resistant organisms vulnerable to a new form of treatment.

Pseudomonas is the first pathogen found to initiate infection after merely attaching to the surface of a host, Princeton University and Dartmouth College researchers report in the journal ...

A social sensing game created at Illinois allows researchers to study natural interactions between children, collect large amounts of data about those interactions and test theories about youth aggression and victimization.

The game's behavior analyses effectively identify classroom bullies, even revealing peer aggression that goes undetected by traditional research methods, the researchers say.

The game's developers say it is an improvement over traditional research methods, such as questionnaires, which do not assess interactions between youth in real time.

"What ...

When the mouse and human genomes were catalogued more than 10 years ago, an international team of researchers set out to understand and compare the "mission control centers" found throughout the large stretches of DNA flanking the genes. Their long-awaited report, published Nov. 19 in the journal Nature suggests why studies in mice cannot always be reproduced in humans. Importantly, the scientists say, their work also sheds light on the function of DNA's regulatory regions, which are often to blame for common chronic human diseases.

"Most of the differences between mice ...

Microbiologists at NYU Langone Medical Center say they have what may be the first strong evidence that the natural presence of viruses in the gut -- or what they call the 'virome' -- plays a health-maintenance and infection-fighting role similar to that of the intestinal bacteria that dwell there and make up the "microbiome."

In a series of experiments in mice that took two years to complete, the NYU Langone team found that infection with the common murine norovirus, or MNV, helped mice repair intestinal tissue damaged by inflammation and helped restore the gut's immune ...

For years, scientists have considered the laboratory mouse one of the best models for researching disease in humans because of the genetic similarity between the two mammals. Now, researchers at the Stanford University School of Medicine have found that the basic principles of how genes are controlled are similar in the two species, validating the mouse's utility in clinical research.

However, there are important differences in the details of gene regulation that distinguish us as a species.

"At the end of the day, a lot of the genes are identical between a mouse and ...

For more than a century, the laboratory mouse (Mus musculus) has stood in for humans in experiments ranging from deciphering disease and brain function to explaining social behaviors and the nature of obesity. The small rodent has proven to be an indispensable biological tool, the basis for decades of profound scientific discovery and medical progress.

But in new findings published online Nov. 19 in the journal Nature, researchers at the University of California, San Diego School of Medicine and Ludwig Cancer Research, with colleagues across the country and world, have ...

TALLAHASSEE, Fla. -- A new line of research from a team at Florida State University is pushing the limits on what the world knows about how human genetic material is replicated and what that means for people with diseases where the replication process is disrupted, such as cancer.

The team, lead by Department of Biological Sciences Professor David Gilbert and post-doctoral researcher Ben Pope, has taken an in-depth look at how DNA and the associated genetic material replicate and organize within a cell's nucleus. Their work could be especially crucial for doctors and ...

BOSTON - November 19, 2014 - Each year in the Northern Hemisphere, levels of atmospheric carbon dioxide (CO2) drop in the summer as plants inhale, and then climb again as they exhale and decompose after their growing season. Over the past 50 years, the size of this seasonal swing has increased by as much as half, for reasons that aren't fully understood. Now a team of researchers led by Boston University scientists has shown that agricultural production may generate up to a quarter of the increase in this seasonal carbon cycle, with corn playing a leading role.

"In the ...

ANN ARBOR--In a study that identifies a new, "direct fingerprint" of human activity on Earth, scientists have found that agricultural crops play a big role in seasonal swings of carbon dioxide in the atmosphere.

The new findings from Boston University, the University of Michigan and other institutions reveal a nuance in the carbon cycle that could help scientists understand and predict how Earth's vegetation will react as the globe warms.

Agriculture amplifies carbon dioxide fluctuations that happen every year. Plants suck up CO2 in the spring and summer as they blossom. ...