(Press-News.org) Coral reefs persist in a balance between reef construction and reef breakdown. As corals grow, they construct the complex calcium carbonate framework that provides habitat for fish and other reef organisms. Simultaneously, bioeroders, such as parrotfish and boring marine worms, breakdown the reef structure into rubble and the sand that nourishes our beaches. For reefs to persist, rates of reef construction must exceed reef breakdown. This balance is threatened by increasing atmospheric carbon dioxide, which causes ocean acidification (decreasing ocean pH). Prior research has largely focused on the negative impacts of ocean acidification on reef growth, but new research this week from scientists at the Hawai'i Institute of Marine Biology (HIMB), based at the University of Hawai'i - Mānoa (UHM), demonstrates that lower ocean pH also enhances reef breakdown: a double-whammy for coral reefs in a changing climate.

To measure bioerosion, researchers deployed small blocks of calcium carbonate (dead coral skeleton) onto the reef for one year. Traditionally, these blocks are weighed before and after deployment on the reef; however, HIMB scientists used microCT (a high-resolution CT scan) to create before and after 3-D images of each block. According to Nyssa Silbiger, lead author of the study and doctoral candidate at HIMB, this novel technique provides a more accurate measurement of accretion and erosion rates.

The researchers placed the bioerosion blocks along a 100-ft transect on shallow coral reef in Kāne'ohe Bay, Hawai'i, taking advantage of natural variability of pH in coastal reefs. The study compared the influence of pH, resource availability, temperature, distance from shore, and depth on accretion-erosion balance. Among all measured variables, pH was the strongest predictor of accretion-erosion. Reefs shifted towards higher rates of erosion in more acidic water - a condition that will become increasingly common over the next century of climate change.

VIDEO:

This is a video visualizing a 3-D reconstruction of a µCT scan of an experimental coral block after a one-year deployment in Kāne'ohe Bay, Hawai'i....

Click here for more information.

This study also highlights the impact of fine-scale variation in coastal ocean chemistry on coral reefs. Current models from the International Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) predict changes in pH for the open ocean, but these predictions are problematic for coral reefs, which are embedded in highly variable coastal ecosystems. The study found dramatic differences in ocean pH and in the daily variability of pH across a short distance.

"It was surprising to discover that small-scale changes in the environment can influence ecosystem-level reef processes," said Silbiger. "We saw changes in pH on the order of meters and those small pH changes drove the patterns in reef accretion-erosion."

Silbiger and colleagues are learning all they can from the microCT scans, as this is the first time before-and-after microCT scans were used as a measure of accretion-erosion on coral reefs. In ongoing work, they are using this technology to distinguish between accretion and erosion and to single out erosion scars from specific bioeroder groups (e.g., holes from boring worms versus bioeroding sponges). The researchers are also using this technology to investigate the drivers of the accretion-erosion balance over the much larger area of the Hawaiian Archipelago.

INFORMATION:

NJ Silbiger, O Guadoyal, FIM Thomas, MJ Donahue (2014) Reefs shift from net accretion to net erosion along a natural environmental gradient. Marine Ecology Progress Series, vol. 515, doi: 10.3354/meps10999

The School of Ocean and Earth Science and Technology at the University of Hawaii at Manoa was established by the Board of Regents of the University of Hawai'i in 1988 in recognition of the need to realign and further strengthen the excellent education and research resources available within the University. SOEST brings together four academic departments, three research institutes, several federal cooperative programs, and support facilities of the highest quality in the nation to meet challenges in the ocean, earth and planetary sciences and technologies.

LIND, Wash. - In the world's driest rainfed wheat region, Washington State University researchers have identified summer fallow management practices that can make all the difference for farmers, water and soil conservation, and air quality.

Wheat growers in the Horse Heaven Hills of south-central Washington farm with an average of 6-8 inches of rain a year. Wind erosion has caused blowing dust that exceeded federal air quality standards 20 times in the past 10 years.

"Some of these events caused complete brown outs, zero visibility, closed freeways," said WSU research ...

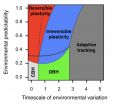

Researchers from North Carolina State University have created a model that mimics how differently adapted populations may respond to rapid climate change. Their findings demonstrate that depending on a population's adaptive strategy, even tiny changes in climate variability can create a "tipping point" that sends the population into extinction.

Carlos Botero, postdoctoral fellow with the Initiative on Biological Complexity and the Southeast Climate Science Center at NC State and assistant professor of biology at Washington State University, wanted to find out how diverse ...

Last year, University of Pennsylvania researchers Alexander J. Stewart and Joshua B. Plotkin published a mathematical explanation for why cooperation and generosity have evolved in nature. Using the classical game theory match-up known as the Prisoner's Dilemma, they found that generous strategies were the only ones that could persist and succeed in a multi-player, iterated version of the game over the long term.

But now they've come out with a somewhat less rosy view of evolution. With a new analysis of the Prisoner's Dilemma played in a large, evolving population, they ...

MEDFORD/SOMERVILLE, Mass. (Nov. 24, 2014, 3 P.M.) -- Researchers at Tufts University, in collaboration with a team at the University of Illinois at Champaign-Urbana, have demonstrated a resorbable electronic implant that eliminated bacterial infection in mice by delivering heat to infected tissue when triggered by a remote wireless signal. The silk and magnesium devices then harmlessly dissolved in the test animals. The technique had previously been demonstrated only in vitro. The research is published online in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences Early ...

A Jackson Laboratory research team has found that the misfolded proteins implicated in several cardiac diseases could be the result not of a mutated gene, but of mistranslations during the "editing" process of protein synthesis.

In 2006 the laboratory JAX Professor and Howard Hughes Medical Investigator Susan Ackerman, Ph.D., showed that the movement disorders in a mouse model with a mutation called sti (for "sticky," referring to the appearance of the animal's fur) were due to malformed proteins resulting from the incorporation of the wrong amino acids into proteins ...

Research that provides a new understanding of how bacterial toxins target human cells is set to have major implications for the development of novel drugs and treatment strategies.

Cholesterol-dependent cytolysins (CDCs) are toxins produced by major bacterial pathogens, most notably Streptococcus pneumoniae and group A streptococci, which collectively kill millions of people each year.

The toxins were thought to work by interacting with cholesterol in target cell membranes, forming pores that bring about cell death.

Published today in the prestigious journal Proceedings ...

A commonly prescribed muscle relaxant may be an effective treatment for a rare but devastating form of diabetes, researchers at Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis report.

The drug, dantrolene, prevents the destruction of insulin-producing beta cells both in animal models of Wolfram syndrome and in cell models derived from patients who have the illness.

Results are published Nov. 24 in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (PNAS) Online Early Edition.

Patients with Wolfram syndrome typically develop type 1 diabetes as very young children ...

(Edmonton) A team of researchers from the University of Alberta has discovered a new approach to fighting breast and thyroid cancers by targeting an enzyme they say is the culprit for the "vicious cycle" of tumour growth, spread and resistance to treatment.

A team led by University of Alberta biochemistry professor David Brindley found that inhibiting the activity of an enzyme called autotaxin decreases early tumour growth in the breast by up to 70 per cent. It also cuts the spread of the tumour to other parts of the body (metastasis) by a similar margin. Autotaxin is ...

High blood pressure and nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) are two emerging health problems related to the epidemic of childhood obesity. In a recent study, researchers at University of California, San Diego School of Medicine sought to determine the prevalence of high blood pressure in children with NAFLD, which places them at risk for premature cardiovascular disease.

The study, published in the November 24 edition of PLOS ONE, found that children with NAFLD are at substantial risk for high blood pressure, which is commonly undiagnosed.

"As a result of our ...

PRINCETON, N.J.--A team led by researchers from Princeton University, Michigan State University and the Indonesian Institute of Sciences have confirmed the discovery of a new bird species more than 15 years after the elusive animal was first seen on the Indonesian island of Sulawesi.

The newly named Sulawesi streaked flycatcher (Muscicapa sodhii), distinguished by its mottled throat and short wings, was found in the forested lowlands of Sulawesi where it had last been observed. The researchers report in PLOS ONE that the new species is markedly different from other flycatchers ...