(Press-News.org) Researchers from North Carolina State University have created a model that mimics how differently adapted populations may respond to rapid climate change. Their findings demonstrate that depending on a population's adaptive strategy, even tiny changes in climate variability can create a "tipping point" that sends the population into extinction.

Carlos Botero, postdoctoral fellow with the Initiative on Biological Complexity and the Southeast Climate Science Center at NC State and assistant professor of biology at Washington State University, wanted to find out how diverse populations of organisms might cope with quickly changing, less predictable climate variations.

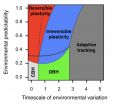

"Organisms tend to adopt a strategy for dealing with changes in their environment," Botero says. "Some of them adjust their gene expression either at birth or throughout their lifetime, which we refer to as irreversible and reversible plasticity. Some do what we call 'bet-hedging,' producing offspring that are adapted to one of two possible outcomes so that at least half of their offspring survive, and some rely on plain old evolution - which we call adaptive tracking - to keep up with environmental changes. We wanted to determine which strategies worked best under certain circumstances, and find the point at which that strategy would no longer be viable."

Botero and colleagues Franz Weissing from the University of Groningen, Netherlands, Jonathan Wright from the Norwegian University of Science and Technology and Dustin Rubenstein from Columbia University, created virtual organisms that were able to modify their insulation - or how they might respond to temperature changes through coat thickness, sweating, etc. - to adapt to the environment, and then placed them in simulations with areas of fast and slow temperature variation and high and low predictability.

The results mapped to a series of "zones" where each adaptive strategy worked best. For example, organisms that used reversible plasticity as a strategy did better in a highly predictable environment, even if the rate of environmental change was rapid. Organisms that relied on adaptive tracking, however, did fine regardless of predictability, as long as the rate of change was slow.

But when the organism got close to the edge of its zone, the smallest variation in either predictability or rate of change led to rapid extinction. The researchers found that these tipping points could occur even with changes that seemed statistically insignificant.

"These results were in line with what we would expect," Botero says. "Within their zones, most of these strategies allow for some variability - and in some cases, the changes within zones can be really huge without much effect on the organism. But when the organism gets close to the margin of another zone, even the tiniest change in either predictability or rate of environmental change can result in immediate extinction, because the initial adaptive strategy no longer works.

"We hope that this model can serve as a first step in the process of locating populations that exist close to these boundary areas, so we can better identify species that are most at risk of extinction."

INFORMATION:

The research appears in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

Note to editors: The abstract of the paper follows.

DOI: 10.1073/pnas.1408589111

"Evolutionary tipping points in the capacity to adapt to environmental change"

Authors: Carlos A. Botero, Initiative for Biological Complexity and the Department of the Interior Southeast Climate Science Center, North Carolina State University and

Washington University; Franz J. Weissing, University of Groningen, The Netherlands; Jonathan Wright, Norwegian University of Science and Technology, Norway; Dustin R. Rubenstein, Columbia University

Published: Online in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences

Abstract:

In an era of rapid climate change there is a pressing need to understand how organisms will cope with faster and less predictable variation in environmental conditions. Here we develop a unifying model that predicts evolutionary responses to environmentally driven fluctuating selection, and use this theoretical framework to explore the potential consequences of altered environmental cycles. We first show that the parameter space determined by different combinations of predictability and timescale of environmental variation is partitioned into distinct regions where a single mode of response (reversible phenotypic plasticity, irreversible phenotypic plasticity, bet-hedging, or adaptive tracking) has a clear selective advantage over all others. We then demonstrate that although significant environmental changes within these regions can be accommodated by evolution, most changes that involve transitions between regions result in rapid population collapse and often extinction. Thus, the boundaries between response mode regions in our model correspond to 'evolutionary tipping points' where even minor changes in environmental parameters can have dramatic and disproportionate consequences on population viability. Finally, we discuss how different life histories and genetic

37 architectures may influence the location of tipping points in parameter space and the likelihood of extinction during such transitions. These insights can help identify and address some of the cryptic threats to natural populations that are likely to result from any natural or human-induced change in environmental conditions. They also demonstrate the potential value of evolutionary thinking in the study of global climate change.

Media Contact:

Carlos Botero,

carlos.botero.p@gmail.com

Tracey Peake, News Services, 919/515-6142 or

tracey_peake@ncsu.edu

Last year, University of Pennsylvania researchers Alexander J. Stewart and Joshua B. Plotkin published a mathematical explanation for why cooperation and generosity have evolved in nature. Using the classical game theory match-up known as the Prisoner's Dilemma, they found that generous strategies were the only ones that could persist and succeed in a multi-player, iterated version of the game over the long term.

But now they've come out with a somewhat less rosy view of evolution. With a new analysis of the Prisoner's Dilemma played in a large, evolving population, they ...

MEDFORD/SOMERVILLE, Mass. (Nov. 24, 2014, 3 P.M.) -- Researchers at Tufts University, in collaboration with a team at the University of Illinois at Champaign-Urbana, have demonstrated a resorbable electronic implant that eliminated bacterial infection in mice by delivering heat to infected tissue when triggered by a remote wireless signal. The silk and magnesium devices then harmlessly dissolved in the test animals. The technique had previously been demonstrated only in vitro. The research is published online in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences Early ...

A Jackson Laboratory research team has found that the misfolded proteins implicated in several cardiac diseases could be the result not of a mutated gene, but of mistranslations during the "editing" process of protein synthesis.

In 2006 the laboratory JAX Professor and Howard Hughes Medical Investigator Susan Ackerman, Ph.D., showed that the movement disorders in a mouse model with a mutation called sti (for "sticky," referring to the appearance of the animal's fur) were due to malformed proteins resulting from the incorporation of the wrong amino acids into proteins ...

Research that provides a new understanding of how bacterial toxins target human cells is set to have major implications for the development of novel drugs and treatment strategies.

Cholesterol-dependent cytolysins (CDCs) are toxins produced by major bacterial pathogens, most notably Streptococcus pneumoniae and group A streptococci, which collectively kill millions of people each year.

The toxins were thought to work by interacting with cholesterol in target cell membranes, forming pores that bring about cell death.

Published today in the prestigious journal Proceedings ...

A commonly prescribed muscle relaxant may be an effective treatment for a rare but devastating form of diabetes, researchers at Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis report.

The drug, dantrolene, prevents the destruction of insulin-producing beta cells both in animal models of Wolfram syndrome and in cell models derived from patients who have the illness.

Results are published Nov. 24 in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (PNAS) Online Early Edition.

Patients with Wolfram syndrome typically develop type 1 diabetes as very young children ...

(Edmonton) A team of researchers from the University of Alberta has discovered a new approach to fighting breast and thyroid cancers by targeting an enzyme they say is the culprit for the "vicious cycle" of tumour growth, spread and resistance to treatment.

A team led by University of Alberta biochemistry professor David Brindley found that inhibiting the activity of an enzyme called autotaxin decreases early tumour growth in the breast by up to 70 per cent. It also cuts the spread of the tumour to other parts of the body (metastasis) by a similar margin. Autotaxin is ...

High blood pressure and nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) are two emerging health problems related to the epidemic of childhood obesity. In a recent study, researchers at University of California, San Diego School of Medicine sought to determine the prevalence of high blood pressure in children with NAFLD, which places them at risk for premature cardiovascular disease.

The study, published in the November 24 edition of PLOS ONE, found that children with NAFLD are at substantial risk for high blood pressure, which is commonly undiagnosed.

"As a result of our ...

PRINCETON, N.J.--A team led by researchers from Princeton University, Michigan State University and the Indonesian Institute of Sciences have confirmed the discovery of a new bird species more than 15 years after the elusive animal was first seen on the Indonesian island of Sulawesi.

The newly named Sulawesi streaked flycatcher (Muscicapa sodhii), distinguished by its mottled throat and short wings, was found in the forested lowlands of Sulawesi where it had last been observed. The researchers report in PLOS ONE that the new species is markedly different from other flycatchers ...

November 24, 2014 - Differences in breast size have a significant mental health impact in adolescent girls, affecting self-esteem, emotional well-being, and social functioning, reports the December issue of Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery®, the official medical journal of the American Society of Plastic Surgeons (ASPS).

More than just a "cosmetic issue," breast asymmetry can have negative psychological and emotional effects, according to the study by ASPS Member Surgeon Dr. Brian I. Labow and colleagues of Boston Children's Hospital. They suggest that early intervention ...

November 24, 2014 - For women considering breast reduction surgery, initial evaluation at a shared medical appointment (SMA) provides excellent patient satisfaction in a more efficient clinic visit, reports a study in the December issue of Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery®, the official medical journal of the American Society of Plastic Surgeons (ASPS).

Shared medical appointments have additional benefits, including "group learning, peer support, and a sense of solidarity and commonality" among women learning about breast reduction surgery, according to the study ...