(Press-News.org) A higher surge of testosterone in competition, the so-called "winner effect," is not actually related to winning, suggests a new study of intercollegiate cross country runners.

The International Journal of Exercise Science published the research, led by David Edwards, a professor of psychology at Emory University, and his graduate student Kathleen Casto.

"Many people in the scientific literature and in popular culture link testosterone increases to winning," Casto says. "In this study, however, we found an increase in testosterone during a race regardless of the athletes' finish time. In fact, one of the runners with the highest increases in testosterone finished with one of the slowest times."

The study, which analyzed saliva samples of participants, also showed that testosterone levels rise in athletes during the warm-up period.

"It's surprising that not only does competition itself, irrespective of outcome, substantially increase testosterone, but also that testosterone begins to increase before the competition even begins, long before status of winner or loser are determined," Casto says.

Casto was a Division I cross country runner as an undergraduate at the University of North Carolina, Wilmington. She majored in psychology and chemistry and became interested in the hormonal correlates of competition in women. She applied as a graduate student in psychology at Edwards' lab when she learned about his work.

Edwards has been collecting data since 1999 on hormone levels of Emory sports teams that have volunteered to participate. The research has primarily involved women athletes. Edwards' lab also developed a questionnaire to measure the status of an athlete. Members of the team rate the leadership ability of other individuals on the team, to provide a combined rating score for each of the participating athletes.

Many of the labs' previous studies involved sports such as volleyball and soccer that require team coordination, intermittent physical exertion and only overall team outcomes of win or loss. Casto wanted to investigate how hormones relate to individual performance outcomes in cross country racing.

Cross country racing is both a team and individual sport. Teams are evaluated through a points-scoring system, but runners are also judged on their individual times, clearly ranking their success in an event.

"Cross country running is a unique sport. It's associated with a drive to compete and perseverance against pain over a relatively long period of time," Casto says. "It's an intense experience."

Participants in the study were consenting members of the 2010 and 2011 Emory varsity men's and women's cross country teams. Each participant provided three saliva samples: One before warming up (to serve as a baseline), one after warming up, and a third immediately after crossing the finish line.

Testosterone went up from the baseline for both men and women during the warm-up, while levels of cortisol - a hormone related to stress - did not.

At the end of the race, both men and women participants showed the expected increases in cortisol and surges in testosterone. Neither hormone, however, was related to finish time.

This research follows on the heels of a 2013 study of women athletes in a variety of sports by Edwards and Casto, published in Hormones and Behavior. They found that, provided levels of the stress hormone cortisol were low, the higher a woman's testosterone, the higher her status with teammates.

The body uses cortisol for vital functions like metabolizing glucose. "Over short periods, an increase in cortisol can be a good thing, but over long periods of chronic stress, it is maladaptive," Casto says. "Among groups of women athletes, achieving status may require a delicate balance between stress and the actions or behaviors carried out as a team leader."

Higher baseline levels of testosterone have been linked to long-term strength and power, such as higher status positions in companies.

"Although short-term surges of testosterone in competition have been associated with winning, they may instead be indicators of a psychological strength for competition, the drive to win," Casto says.

INFORMATION:

Anglers across the nation wondering why luck at their favorite fishing spot seems to have dried up may have a surprising culprit: a mine miles away, even in a different state.

Scientists at Michigan State University (MSU) have taken a first broad look at the impacts of mines across the country- and found that mining can damage fish habitats miles downstream, and even in streams not directly connected to the mines.

The work is published in this week's issue of the journal Ecological Indicators.

"We've been surprised that even a single mine in headwaters might influence ...

Australian average incomes are falling with the country's population growth "masking underlying economic weakness", according to a QUT economist.

Dr Mark McGovern, a senior lecturer in QUT's Business School, said while it was regularly proclaimed Australia had experienced positive economic growth for more than 20 years, there had been periodic per capita declines, indicating the economy was not as healthy as assumed.

"Looking at national income figures in recent years shows our economy is under stress," Dr McGovern, whose research was recently published in the Economic ...

Few agribusinesses or governments regulate the types of plants that farmers use in their pastures to feed their livestock, according to an international team of researchers that includes one plant scientist from Virginia Tech.

The problem is most of these so-called pasture plants are invasive weeds.

In a Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences study this month, the scientists recommended tighter regulations, including a fee for damage to surrounding areas, evaluation of weed risk to the environment, a list of prohibited species based on this risk, and closer ...

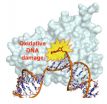

Using a new imaging technique, National Institutes of Health researchers have found that the biological machinery that builds DNA can insert molecules into the DNA strand that are damaged as a result of environmental exposures. These damaged molecules trigger cell death that produces some human diseases, according to the researchers. The work, appearing online Nov. 17 in the journal Nature, provides a possible explanation for how one type of DNA damage may lead to cancer, diabetes, hypertension, cardiovascular and lung disease, and Alzheimer's disease.

Time-lapse crystallography ...

PHILADELPHIA (Nov. 25, 2014) - As the linked epidemics of obesity and diabetes continue to escalate, a staggering one in five U.S. adults is projected to have diabetes by 2050.

Ground zero for identifying ways to slow and stop that rise is Philadelphia, which has the highest diabetes rate among the nation's largest cities. For public health researchers at Drexel University, it is also a prime location to learn how neighborhood and community-level factors -- not just individual factors like diet, exercise and education-- influence people's risk.

A new Drexel study published ...

PITTSBURGH, Nov. 24, 2014 -Barriers to the sharing of public health data hamper decision-making efforts on local, national and global levels, and stymie attempts to contain emerging global health threats, an international team led by the University of Pittsburgh Graduate School of Public Health announced today.

The analysis, published in the journal BMC Public Health and funded by the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation and the National Institutes of Health (NIH), classifies and examines the barriers in order to open a focused international dialogue on solutions.

"Data on ...

The proper regulation of body size is of fundamental importance, but the mechanisms that stop growth are still unclear. In a study now published in the scientific journal eLife*, a research group from Instituto Gulbenkian de Ciência (IGC), led by Christen Mirth, shed new light on how animals regulate body size. The researchers uncovered important clues about the molecular mechanisms triggered by environmental conditions that ultimately affect final body size. They show that the timing of synthesis of a steroid hormone called ecdysone is sensitive to nutrition in the ...

People's views on income inequality and wealth distribution may have little to do with how much money they have in the bank and a lot to do with how wealthy they feel in comparison to their friends and neighbors, according to new findings published in Psychological Science, a journal of the Association for Psychological Science.

"Our research shows that subjective feelings of wealth or poverty motivate people's attitudes toward redistribution, quite independently of objective self-interest," says psychological scientist and study co-author Keith Payne of the University ...

WASHINGTON, Nov. 25, 2014 -- Your beer may attract annoying fruit flies, but listen up before you give them a swat. Researchers found the yeast cells in beer are producing odor compounds -- acetate esters -- that lure flies and that could lead to the best beer you haven't even tasted yet. This week's Speaking of Chemistry explains why. Check it out at http://youtu.be/HQNlGuZvCvA.

Speaking of Chemistry is a production of Chemical & Engineering News, a weekly magazine of the American Chemical Society. The program features fascinating, weird and otherwise interesting chemistry ...

Bitcoin is the new money: minted and exchanged on the Internet. Faster and cheaper than a bank, the service is attracting attention from all over the world. But a big question remains: are the transactions really anonymous? Several research groups worldwide have shown that it is possible to find out which transactions belong together, even if the client uses different pseudonyms. However it was not clear if it is also possible to reveal the IP address behind each transaction. This has changed: researchers at the University of Luxembourg have now demonstrated how this is ...